During the run-up to this program, someone asked me whether I intend to guide the participants through the process of reproducing a painting, and I was surprised by the sheer adamance of my own inner “No-no-no!” in response to this question (my actual answer was much milder, of course).

Surprised — because, superficially at least, what I call a “painting study” looks, indeed, like the process of reproducing a painting. And yet, it feels as different as a walk through the woods does from driving (even if the final destination might be the same). Because the essence of this journey is not in reaching the destination; it’s in what you see and how you change in the process, or even in the experience itself.

For me, the process of a painting study from a master — in its various forms — feels like one of the most joyful and transformative of life’s experiences (often more so than just painting), and that is what I want to share with you in this program. It intertwines three motives, three deeply related experiences.

First, it is learning by doing — the best way to learn in many realms, but hardly anywhere more so than in painting. “Theoretical” knowledge, however rich and extensive — something residing in one’s head — helps but a little (if at all) in this domain. Painting is a very “bodily” endeavor in many ways, and the requisite knowledge permeates through the whole “eye-head-heart-hand” system. Following a masterpiece with your own eye and your own hand somewhat mysteriously transforms your head and heart in the process.

Secondly, it’s a deep, complete connection with the masterpiece being studied — deeper and more complete than anyone can achieve simply by looking at it; knowing it (almost literally) inside out. It is often hard to believe (or even imagine) in advance how much one can discover in a great painting through the process of painting study.

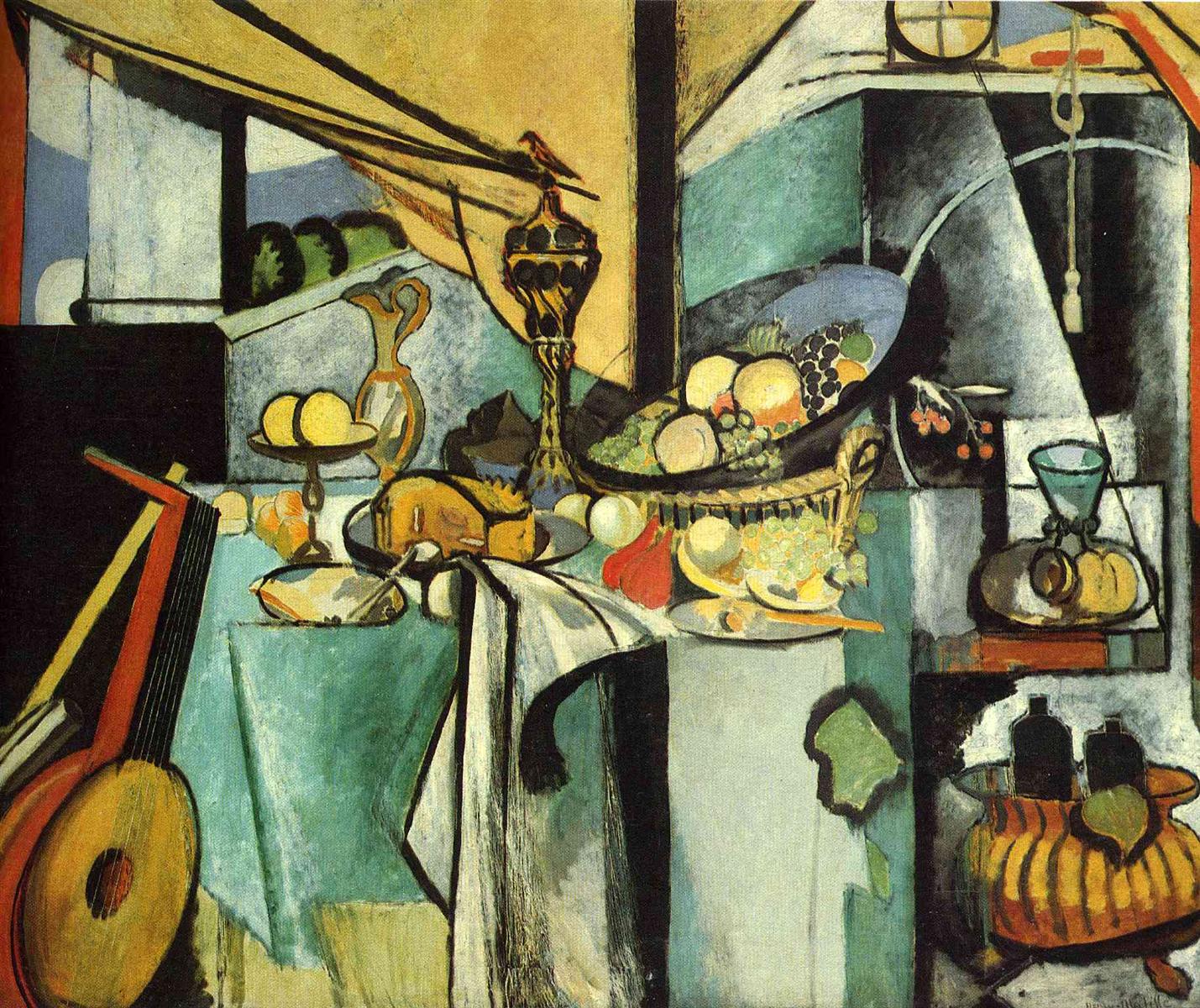

And then, there is what can only be described as the experience of conversation with the master, participation — however humble — in the timeless unity between artists of all ages. Matisse’s painting which illustrates this post is one of the greatest examples of such a dialogue across ages (here, by the way, is the masterpiece he was working from).

The process, therefore, is very different from the making of a “handmade reproduction”. Perhaps the easiest way to illustrate this difference is to consider the approach to “drawing” in each case; “drawing” in its most basic sense: getting “things” look like they do in the original, and putting them into the right spots on the canvas.

If one’s goal is to just make an exact reproduction, there can be nothing more natural (or even occasionally necessary) than to use some form of tracing, and/or precise measurements to reproduce all the shapes and lines as precisely as possible. After all, how the accuracy in reproduction is achieved is immaterial for the client — so the painter would be well advised to get these things right by any means available.

In the process of a painting study, it is often also essential to get the shapes and lines right, if only because the core assumption of such a study is that nothing is random in a masterpiece: if a line goes at a certain angle, there is a deep reason for that. But it would defy the purpose completely if we try to reproduce this angle by tracing, exact measurements, projections, or any other devices. This superficial, purely technical approach won’t ever allow you to understand, to feel it in your bones, why each line goes exactly as it does, why it is here and not there.

This deep understanding is not about being able to give a logical explanation of why it should be so, but about ingrained, sensual, embodied knowledge that transforms you as an artist. It may sound mysterious (even though I am sure there is some very scientific explanation for this), but the process of drawing a line “right” using your own eye-head-heart-hand does engender this learning transformation (even if the head alone could never know what actually happened).

The same difference applies to all aspects of painting study, and can be best captured by the metaphor of surface versus depth. With a sufficient skill level, one can make a successful reproduction while staying completely on the surface of things — just as social skills would allow a person to have an “interesting” conversation without ever connecting deeply to its topic, nor listening deeply to others. Or, to return to my first metaphor, like a highway would allow a skilled driver to reach the other side of a forest without really seeing any single tree of it.

But for a successful painting study, one has to dive deeply into the painting’s essence, and re-create the painting from this depth. Ideally — from a place where you feel that there is simply no other way to paint this painting, coming as close as possible to what Kandinsky called the “inner need” of the artist who created the masterpiece you are studying.

The fundamental need for this “deep dive” is the rationale behind the sequence of “preliminary studies” (or “practices”) that I will be suggesting during the first three weeks of the program. They are intended to gradually lead you to the place where you know exactly how to approach the blank canvas of your final study, where you (almost) feel the same “inner need”. And this dive will begin somewhat unconventionally — not with drawing or design, but with color; because color is the very essence of painting.