Charles Darwin once wrote:

Man still bears in his bodily frame the indelible stamp of his lowly origin.

Two ideas combined in one short sentence: the observation of past being ever-present in the present, and this seductive idea of progress, onward and upward movement of humankind from its lowly origin.

There is, of course, also a completely opposite view of human history: in the past, ever visible in the present, it sees not the humanity’s lowly origin, but its Golden Age. Like the Golden Age of Rousseau’s “noble savage”, roaming the wilderness of nature in solitary freedom, filled to the brim with courage and compassion — and then it was all downhill from there. Friedrich Nietzsche’s hypothesised that pre-historic humans traded their original freedom, their animal power and joy, for “peace and security” provided by community — a theme still being played out, again and again, in contemporary political struggles (except now we have “society” and “state” instead of “community”).

So what has it been: ascent or fall, progress or decay? What do we see in the past so indelibly stamped in our present: the lowly origin or the garden of Eden? There is, obviously, no simple answer — and these two views have been fighting each other forever in the history of human thought.

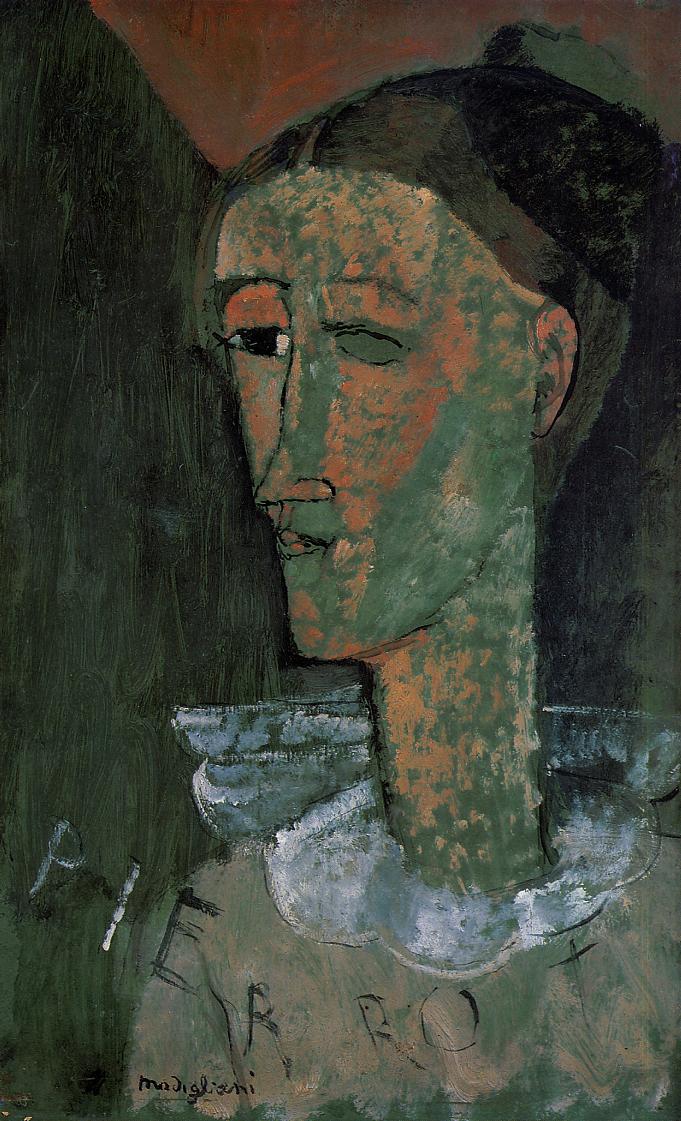

But nowhere does the idea of progress seem more absurd, ridiculous even, as in the realm of visual arts.

None of us could paint like that.

— Pablo Picasso reportedly said about cave paintings. And just one look at a more recent, more immediate “Golden Age”, the art of Ancient Greece, with its unmatchable perfection, is enough to make one throw the idea of progress out of the nearest window.

It may even seem that it only this high origin, still visible in the art of the present (even if only barely) that keeps it alive. As the humankind grows (apparently) richer and more productive, man-made things — from art to architecture to household items — seem to get cheaper, duller, and uglier. I live in a fast-growing city in one of the richest areas of the planet, but the only beauty it appears to be able to afford is to keep some of its trees alive. We have to travel to ancient places, to old cities, or go to museums, just to marvel at the beauty and grandeur humans used to be capable of.

So are we witnessing the death of art? Is it fighting its last losing battle?

In his “Genealogy of Morals”, Nietzsche observes that we tend to confuse the contemporary purpose of something — the meaning and “function” we currently attach to it — with its original cause, the reason for its emergence. But at this particular moment in time, we seem to be having a hard time defining the “function” of art — the phenomenon is still there (against all reasonable odds, it seems) — and we, as a society, have no idea what to “do” with it, why on earth it might be “useful”. There are some attempts to invent plausible uses for art — like a critique or betterment of society, or fostering creativity (which can then be applied to something really useful, like business development), or even “therapy” (that is, making us feel better about our lives). But these uses seem just way too small and “tame” for the phenomenon itself. It’s like keeping a wild tiger in the house for the purpose of adding an orange spot to the colour scheme.

To be sure, there have been some loftier hypotheses about the role of art, especially by artists themselves. According to Wassily Kandinsky, for example, art is a driving force in the spiritual advancement of humankind, its eternal onward-and-upward movement away from its lowly origins. This idea didn’t get much traction, as it seems —maybe because it was immediately followed by two atrocious wars (which put a huge question mark on the idea that any spiritual advancement is going on), or maybe because such ideas are just too grand for the sceptical age of post-modernism. And then again, who really cares about the spiritual advancement of humankind when there are bills to be paid (or the planet to be saved)?

Our inability to figure out the function of art may, in fact, be inevitable. Nietzsche notices that

… all ideas in which an entire process is semiotically summarised elude definition. Only something which has no history is capable of being defined.

So if we have trouble defining the “function” of art in the modern society, it makes sense to contemplate its past — its origin and history, as they are still indelibly stamped in its present state.

Cave paintings represent the first Golden Age of painting we know of — and arguably, the very first one. This was the time when, according to Nietzsche, humans must have first exchanged their freedom and power for the safety of community living. Following his hypothesis, it also means that they had to start suppressing the outward expression of their wild animal instincts in order to fit in. Nietzsche writes:

All instincts which are not discharged to the outside are turned back inside—this is what I call the internalisation [Verinnerlichung] of man. From this first grows in man what people later call his “soul.”

The entire inner world, originally as thin as if stretched between two layers of skin, expanded and extended itself, acquired depth, width, and height, to the extent that what a person discharged out into the world was obstructed.

This, according to Nietzsche, is the origin of inner world and “bad conscience” (that is, our endless internal self-talk, where the mind turns against itself).

The first paintings, then, emerged as a response to this expansion of previously non-existent inner world, to the first separation between the “inner” and the “outer”, between the spiritual and the material. In fact, they might have been an attempt to materialise, make permanent the fleeting projections of the inner world on cave walls. The cave walls were like a membrane between the material and the spiritual — and this membrane was still very thin at the time. This was just the first seed of the spirit-matter duality, which was to grow, eventually, into the almost unbreakable wall we modern humans have to deal with on a daily basis. And the art’s role was to somehow keep the two sides of this divide together.

But the history of art wasn’t really all downhill from this high point; it might have been the first “Golden Age”, but it was certainly not the only one. What we see in art’s history is some epochs of incredible, peak achievements, and the ages of stagnation and decay in between. So what I want to do in this new series, “Art in the age of consciousness”, is to look at some of the highest peaks in the history of art from its origin to the present time, and to try and figure out whether there was some sort of shared cause, a common theme to these recurrences of the original Golden Age.

For me, it’s not an academic exercise, but an attempt to understand the present state of art in the grand scheme of things — and, ultimately, the part we have to play on this stage.