Have you heard that art is subjective?

I am sure you have, but if not, I would dearly love to live in your world, because I hear it all too often.

Most often, it seems, it is just a fancy way of saying “You don’t need to like what I like, and that’s fine”. Thus, it is a statement about the experience of art, which makes it utterly meaningless, because all experiences are subjective.

Our experiences of food are subjective (“If you like ice-cream, and I don’t, that’s fine”). Our experiences of nature are subjective (“If you like climbing mountains, and I don’t, that’s fine”). Even our experiences of mathematics are subjective (“If I find it fascinating, and you, boring, that’s fine, too”). But we don’t go around telling one another that food, and nature, and mathematics are subjective, do we? And if we did, we could just accept, once and for all, that everything is subjective, and stop singling art out for this “special treatment”.

On the other hand, the idea that our experiences of art are truly, deeply subjective — that is, uniquely our own — might be nothing but wishful thinking. Art has generated around itself a whole industry dealing in its presumably “objective” aspects — art dealers, art consultants, art critics, art historians, curators competitions, awards, juries and what not. One has to be fully and completely ignorant in the domain of art not to be at least to some extent influenced by shared, “socially held”, established views.

What about art itself, is it subjective?

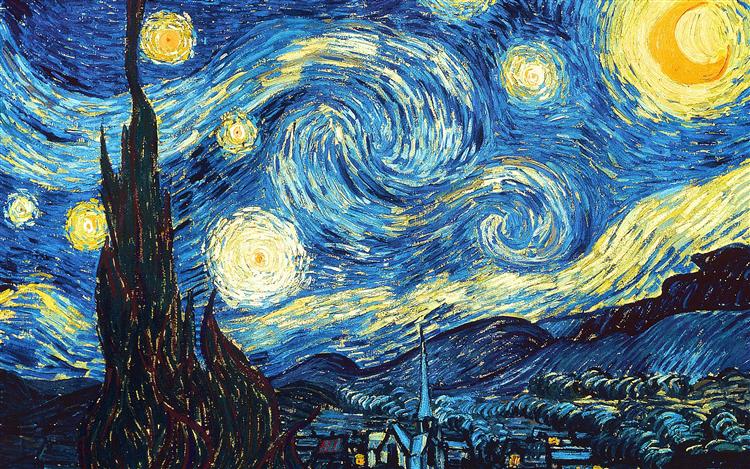

About ten years ago, Van Gogh’s Starry Night made the world news: scientists discovered that the flow of light in this starry sky perfectly captures the pattern of natural turbulence — one of the most complicated natural phenomena known to science. The essence of this discovery is described simply and clearly in the TED-Ed video below, or you can follow the link above if you prefer reading, but the bottom line is this: it took science almost a century to catch up with the artist’s insight into the nature of reality.

This insight has to do with something as uncontroversially objective as it gets — an observable and measurable physical phenomenon. On the other hand, this painting is a peak of subjectivity in art. It was painted in an asylum: it was Van Gogh’s own decision, because he could not really deal with the “objective world” outside, and needed protection from it. He was mentally and emotionally unstable — and what are such states if not a breakdown of interface between the subjective and the objective, the inner and the outer? And, contrary to his preferred practice, it was not painted from life (he wasn’t allowed to leave the asylum at night). He needed to withdraw deep into his inner world in order to come up with this insight into nature.

If there is a lesson in this story, it is that the very opposition between “subjective” and “objective” makes no sense whatsoever in the realm of art.

“Art is subjective” as a mind parasite

I think “art is subjective” is a good example of what Richard Dawkins called “meme” in his famous book, “The selfish gene”: a catchy chunk of language/thought that is good at propagating itself in our minds. The thing about memes is that their ability to survive and self-replicate has little (if anything) to do with being true or false, meaningful or meaningless (memes, like genes, are “selfish” like that).

But that doesn’t mean that they are inconsequential. This one in particular, “art is subjective”, has a potential of changing the reality we live in, because it invokes the fundamental duality of “subjective” versus “objective”, a duality that shapes our life far beyond the realm of art.

Just consider the spectrum of meanings hiding behind these words, “subjective” and “objective”: individual — universal, mind — matter, inner — outer, false (biased) — true, illusory — real, etcetera etcetera. Every time we say or hear that art is subjective, this whole cloud of meanings, and the corresponding network of neural connections, are awakened in our brain. The divide between “subjective” and “objective” is reinforced, and art is firmly placed on the other side from truth and reality. And all this happens independently of what is being meant in each specific case (if anything): that’s just how language and brain work.

And so it happens that the “art is subjective” meme, for all its seeming innocence (“you can like what you like”), constantly recreates and reinforces the disconnect between art and “real life”, art and “objective reality”. It marginalises art and pushes it into obscurity, which may be very far from our conscious intentions when we lend our minds and brains to propagation of this meme. One can simultaneously lament marginalisation of arts and entertain the idea that “art is subjective”.

In other words, “art is subjective” is not just an innocent meme. Rather, it is a “mind parasite”, which “works” against its hosts for its own selfish needs of survival and propagation.

The problem is that simply not believing that art is subjective doesn’t get rid of this parasite — because the opposite belief, “art is objective”, is just as meaningless. The only way, I think, is to disconnect it from the very ground it thrives on, that is, the “subjective-objective” duality itself.