The brain is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will include

With ease, and you beside. — Emily Dickinson

What is often called “realism” in painting is merely the art of projecting three-dimensional objects on two-dimensional surfaces, giving the spectator’s eyes and brain enough visual clues to re-create three-dimensionality “in the mind’s eye”. But there are multiple dimensions of reality that a painter can focus into a two-dimensional image. A landscape, for example, can be a container for multiple sensory dimensions: the smell of its greenery, the taste of its air, the sounds of its waves, the touch of sunlight on your skin.

Pavel Filonov (1883 — 1941) called his style “analytical realism”. The term referred to the process of making a painting, which had to incorporate (and, ultimately, manifest) the analytical power of human mind, the full energy of human cognition. And it was also about the intention of the artist, the intention to go beyond appearances, to analyse a thing in terms of its inner principles and constituent elements — and then to fuse the inner and the outer into the unified reality of a completed painting. He used the Russian word сделанность to refer to a painting being a complete and perfect manifestation of the evolution of artist’s mind in the course of its making (a noun otherwise non-existent in Russian, but transparently derived from the participle сделан, meaning “done, made, completed”).

Our visual reality is shaped by our beliefs, or experiences, our thought patterns anyway. The easy-to-name but hard-to-use “key” to analytical realism is to be constantly aware of this, and to make it fully visible in paintings.

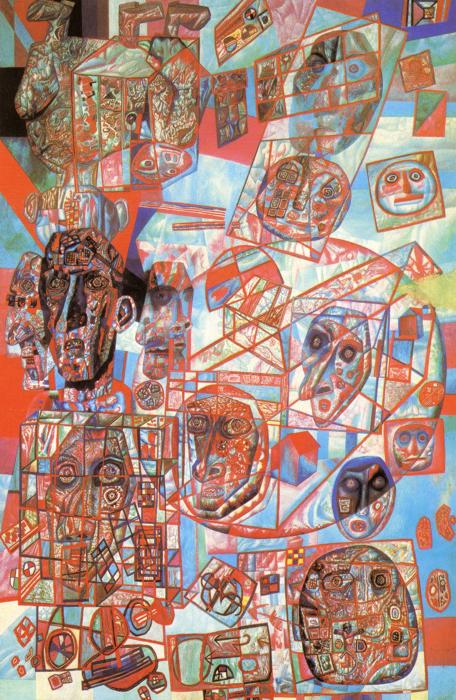

This painting, “A man in the world”, belongs to a large series of “heads”, which Filonov painted over several years: the principles of analytical realism applied to the inner workings of human minds, the mind using its power of analysis to see itself.

The painting is filled with floating human heads viewed from different angles. This may be an insight into the evolution of one man’s thinking processes, or into interactions between different minds, or both. In the end, it doesn’t really matter: we are confronted with the limitations of our minds made visible. We see how the contours of heads are overlaid with rectangular grids, some flat, others three-dimensional. Colour marks fly in and out of the heads, the lines of outer reality intersect and overlap with the inner grids. And occasionally, here and there, there is something more complex, organic, and colourful emerging within some of the heads.

This painting evokes in my mind the memory of first reading Tor Norretranders’ book, “The User Illusion: Cutting Consciousness Down to Size”, many years ago. One of its core insights is the staggering contrast between the dismal amount of information the conscious, thinking mind can process moment-to-moment, and the virtually infinite wealth of stimuli processed by the brain-as-a-whole at the same time, below the threshold of consciousness. The conscious mind likes to feel in control, and so we build for ourselves, whenever possible, a simple world of straight lines, flat surfaces, rectangular spaces — both within our heads, and in the outer world of things.

This book is based on the twentieth century scientific research — psychology, neuroscience, information theory, but Filonov’s painting was completed in 1925, nearly a century ago, well before any of these discoveries. In a sense, the painting defies and transcends itself: it shows us the limitations of the mind, but its very existence witnesses the mind’s incredible, prophetic, power. We see in the painting our simplistic inner maps of reality, and recognise that it is the very process of focusing the mind on seeing them that unleashes its power and makes such a painting possible. The painting is an invitation to look within our heads, and observe these silly rectangular grids as they stifle our consciousness and impoverish our reality.