From “Learning how to Learn from Masters: Module 3. A fork of the road”

Last week, we studied the “geometric” organization of the picture plane — trying to look at the painting just as at the two-dimensional object it really is, and disregarding (or at least trying to disregard) the illusion of space it creates. A tension between two-dimensionality and three-dimensionality lies at the very heart of the art of painting. You will be confronted with it in the process of your final study, so it may be useful to explore how it works in the masterpiece you are studying in advance.

When we consider this tension between 2D and 3D, the plane and the space, in painting, it’s helpful to remember that the raw visual data our eyes receive “in real life”, without mediation of painting, is also “2D”: our “reconstruction” of the visual reality in front of us is based on the patterns of neural excitations on the two “planes” of our retinas. The 3D “effect” arises from “interpretation” happening “deeper” in the brain, and determined, to a large extent, by our prior knowledge of how the reality ought to look like. That’s why the 3D illusion in painting is possible: because our brains are accustomed to reconstructing a 3D reality from 2D visual data.

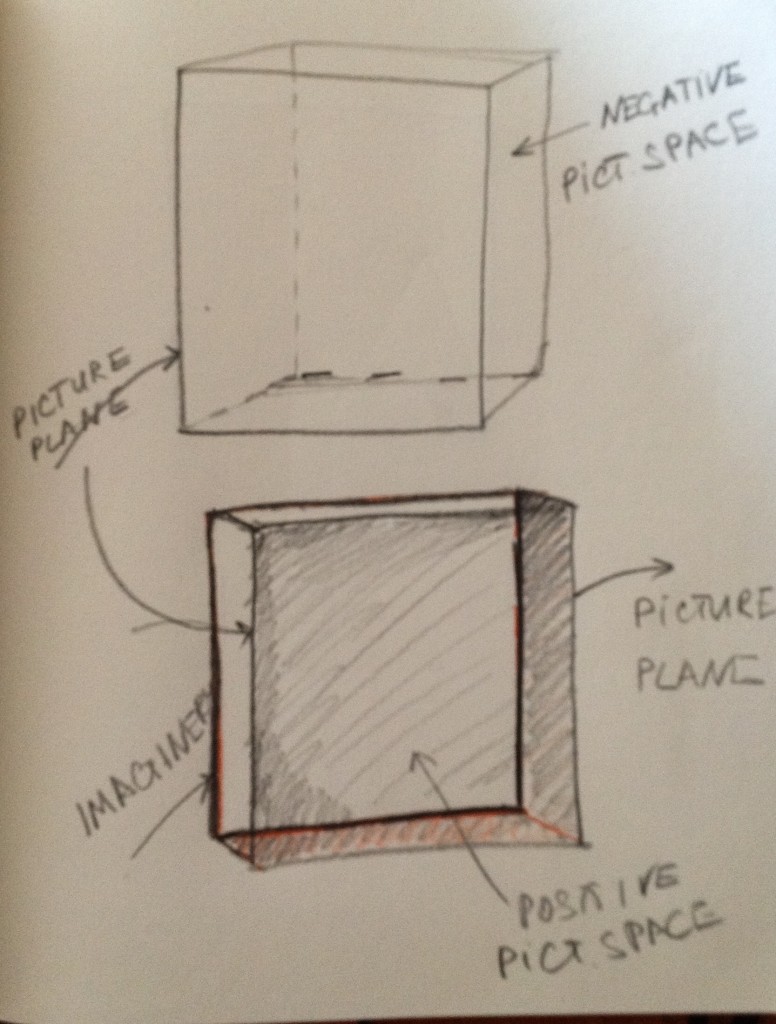

To talk about this illusion and its role in the painting, it will be convenient to use the concept of “picture box” — the imaginary container of the painting’s content. By “cultural default”, the picture box’s “front plane” is the picture plane — all that happens in the painting’s pictorial space, happens behind the picture plane. That’s what we’ve learned to expect from a pictorial space — to be located just behind the picture plane, so that it works as a kind of “glass wall” between the viewer and the pictorial space. This is sometimes called “negative pictorial space”, and, for a modern viewer at least, it keeps the illusion of space “at bay”, under conscious control — we can see both the picture plane and illusion of pictorial space at the same time. In a sense, we can both experience the illusion and see it for what it is.

To talk about this illusion and its role in the painting, it will be convenient to use the concept of “picture box” — the imaginary container of the painting’s content. By “cultural default”, the picture box’s “front plane” is the picture plane — all that happens in the painting’s pictorial space, happens behind the picture plane. That’s what we’ve learned to expect from a pictorial space — to be located just behind the picture plane, so that it works as a kind of “glass wall” between the viewer and the pictorial space. This is sometimes called “negative pictorial space”, and, for a modern viewer at least, it keeps the illusion of space “at bay”, under conscious control — we can see both the picture plane and illusion of pictorial space at the same time. In a sense, we can both experience the illusion and see it for what it is.

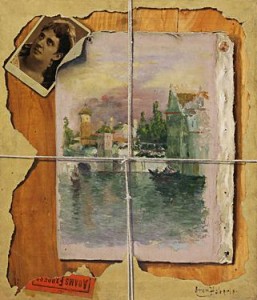

That’s why “trompe-l’œil” paintings — that is, paintings that deliberately try to fool the eye, to create a “real” illusion — tend to “build” a “positive pictorial space”, where at least some objects (or parts of them) seem to be located in front of the picture plane. Luckily, we have one such painting in the program, John Haberle’s “Torn in transit”, so this difference can be easily illustrated: in this painting, the picture plane coincides not with the front plane of the picture box, but with its back plane (the picture plane pretends to be the wooden surface of the box depicted in the painting).

Whereas other paintings aren’t trying to create the “trompe-l’œil” kind of illusion, they vary greatly in how they deal with the tension between the reality of picture plane and the illusion of pictorial space. This, perhaps, is an aspect of painting where the signs of epoch are most visible: the closer we are to our own time, the more the picture plane “dominates” the pictorial space. In Rembrandt, the tension is virtually non-existent; the picture plane is transparent, really like a glass wall; the pictorial space seems almost “real”, undisturbed by its interaction with the picture plane.

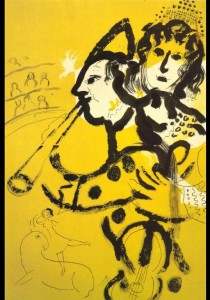

In Chagall and Matisse, the picture plane all but subdues the pictorial space; they deliberately keep the picture visibly “flat”. Even though we are given some clues to suggest that the picture depicts a space, we don’t really see it. The pictorial space collapses as it were under the weight of the picture plane: the smaller objects (and figures) in the distance look as though they are on the same plane as the larger objects in the foreground. It’s only our knowledge that objects appear smaller when they are further away that suggests this interpretation.

In the context of this program, Chagall and Rembrandt give us two “endpoints” of the spectrum of complex relationships between the picture plane and the negative pictorial space, and thus help us perceive the tension in other paintings. They all occupy different spaces of this spectrum: the picture plane is never fully transparent, it changes and moulds the pictorial space. And you will need to see how this happens to understand the inner workings of the painting.

This is the background information to the first question you will have to ask yourself this week: do you feel the need to explore how the pictorial space of “your” masterpiece is organized in advance, before you start the final study? If yes, please read on.