Leo Tolstoy begins “Anna Karenina” with a slow morning ritual of his most harmonious and cheerful character, Anna’s brother, Prince Stepan Arkadyevitch (Stiva) Oblonsky. After breakfast, Stiva reads his paper. Tolstoy writes:

“Stepan Arkadyevitch took in and read a liberal paper, not an extreme one, but one advocating the views held by the majority. And in spite of the fact that science, art, and politics had no special interest for him, he firmly held those views on all these subjects which were held by the majority and by his paper, and he only changed them when the majority changed them—or, more strictly speaking, he did not change them, but they imperceptibly changed of themselves within him. Stepan Arkadyevitch had not chosen his political opinions or his views; these political opinions and views had come to him of themselves, just as he did not choose the shapes of his hat and coat, but simply took those that were being worn. And for him, living in a certain society—owing to the need, ordinarily developed at years of discretion, for some degree of mental activity—to have views was just as indispensable as to have a hat.”

What do you feel as you are reading this?

When I first read this passage as a teenager, all I saw was a caricature of shallowness and total lack of thinking. I felt it had nothing to do with me whatsoever. After all, my own political views were definitely at odds with the majority: I was growing up in a dissident family in the Soviet Union, at the time when dissent was relentlessly persecuted. So I knew for sure that no newspapers are to be trusted.

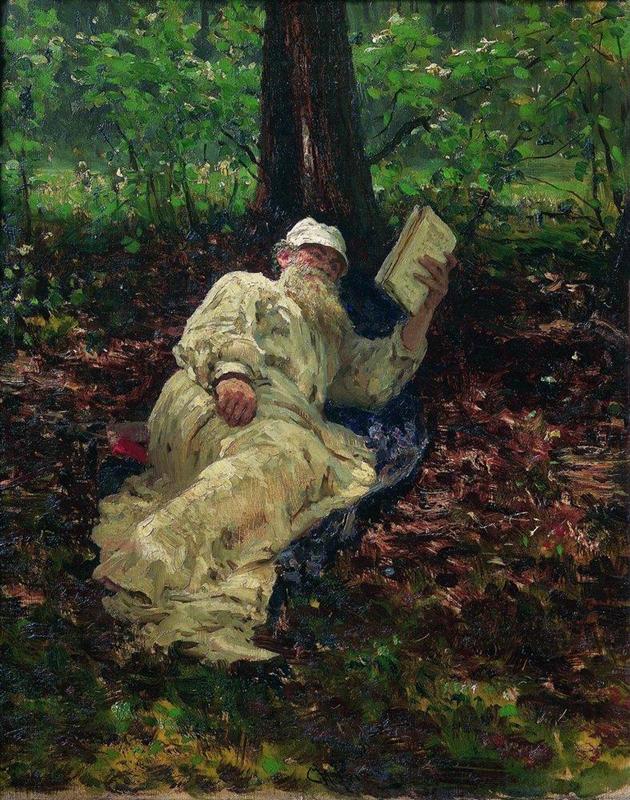

But my response imperceptibly changed as I grew up: I began to recognise myself in this description. And I also realised that this must be, albeit indirectly, a “first person” narrative, even though Tolstoy himself was enough of an outspoken dissenter to be excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church. But the only way he could possibly know this process of unconscious, imperceptible acquisition of consensus so intimately is “from the inside”.

This is not something easy to admit publicly, or even to recognise in oneself in the privacy of one’s mind. It doesn’t fit the modern ideal of a well-informed free-thinking individual at all. This ideal individual’s world view must reflect the objective reality, and they have to build it consciously, through critical observation and thinking — not by blindly following the consensus.

But Stiva’s unconscious way of forming his views is not only universal, it is unavoidable. That’s how we learn so incredibly fast as children, absorbing things imperceptibly, as though breathing them in from the air around us. There is just no other way to acquire all the knowledge we need to function in this world. And to begin with, a child would never learn their native language if they constantly doubted the correctness of what is spoken around them. They have to take in every bit of language they hear as a piece of valid data and (unconsciously) build it into their brains. And, of course, this is also how I acquired the political views my teen self so proudly considered her own when I first read “Anna Karenina” — from my parents and their friends, unconsciously absorbing the consensus from my local environment. They were dissenters in the context of the society as a whole, but I wasn’t a dissenter within the community I was growing up in.

This unconscious appropriation of the socially shared world view feels as though you get to know the objective reality. Stiva Oblonsky doesn’t feel like he accepts the consensus; he just knows what he knows. He doesn’t perceive the gap between his world view and the objective world — and that’s why he generally lives in a child-like, cheerful harmony with his world. And whatever it might be that you or I think we know for sure at this moment, this means we don’t perceive this gap either.

Throughout most of the human history — the tens of millennia of humanity’s childhood — this ever-present gap between the consensus and the reality was even harder to perceive. People lived in closed communities with universally shared world views. Their world view wasn’t a world view for them, it was reality itself, their uncontroversial objective knowledge of the world — and there was no reason to wonder where it came from.

Nowadays, we don’t seem to have this comfort anymore, insofar as we are aware that there are different world views in the world. But the truth is, this awareness itself doesn’t really shake the built-in illusion of knowing the objective reality. We may occasionally notice that “someone on the internet” lives in an “alternative reality”, but that doesn’t often make us doubt the truth of ours, at least not as long as we live in the comfort of local consensus, surrounded by people who share the same world view.

I vividly remember the first time I was really thrown out of this comfort. It happened in a remote Siberian village of Nelemnoye, where I spent several weeks in 1987 studying the Yukaghir language. Although the traditional shamanistic culture had been crushed there long before that (first by the Orthodox Church, then by the Soviets), the Yukaghir still had their own view of reality, quite different from the scientific brand of objectivity I used to take for granted. And it was reflected in a thousand little and not so little things built into their way of life.

There was this old man I met on my first day there, who was waving his hands in the general direction of the sky to chase the clouds away. And at every meal, you had to share a bit of everything with the fire. Before starting a motor boat, you had to offer an apology to the river, because it didn’t like the noise. All in all, every aspect of daily life implied the existence of invisible spirits all around you, a consciousness “out there” in nature you had to interact with humbly and politely.

It was a local consensus entirely different from the one I was accustomed to. I wasn’t consciously willing to adopt it at all, but the job of a field linguist requires one to fit in: if I didn’t feed the fire at every meal, I might as well go home at once. And as the weeks went by, I must have imperceptibly absorbed some of this. The reality, as I perceived it, slightly shifted. There was this weird, distinctly uncomfortable, feeling that I don’t know anymore what is really there and what is not.

It all wore off rather quickly when I left the village; back at home, I was soon back to normal, within the familiar comfort of my “native” consensus.

The disorienting state of losing touch with objective reality I experienced there is known by its Greek name of aporia. It occurs when one recognises that they don’t really know what they thought they knew, that something that has always been out there, in the objective world, may be nothing more than a part of unconsciously absorbed consensus. The sensation is so uncomfortable that Socrates had to die for forcing it on his fellow Athenians. But this is the state that lies in the space between the consensus and the truth.

It might seem that we live in a world completely different from the ancient Athens. There doesn’t seem to be much of a consensus nowadays: wherever you look, there are differing views about everything. You don’t even have to go anywhere to immerse yourself in shamanism: internet will deliver this experience to you if that’s your wish. The humankind has learned from its long experience that the consensus and the objective reality is not the same thing, that there is no path to truth without dissent. At least here in the first world, nobody needs to fear Socrates’ fate now — politically, at least, the freedom of dissent is won.

But this freedom is a treasure that protects itself: even if the fear of external persecution is removed, there are more formidable dragons standing guard within ourselves. One is our hard-wired tendency to absorb the consensus as “objective reality”. The second one is the natural desire to live in harmony with the world. And the third, most powerful one: our need to be certain of objective reality in order to navigate it, the very need that makes the state of aporia so painfully uncomfortable.

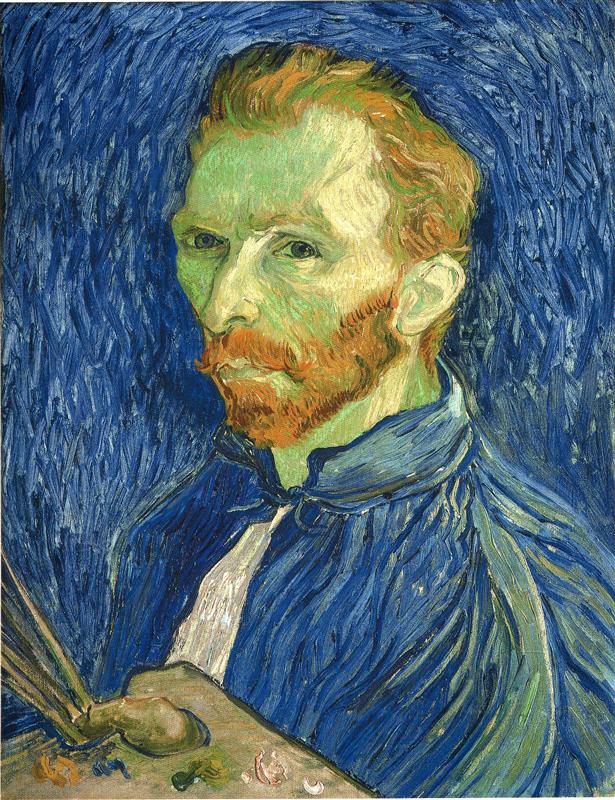

Edgar Degas said that art is not what you see, but what you make others see. But in order to make others see something they don’t see, you first have to see it yourself (be it within your inner world, or out there, in the world of appearance). That’s not all, of course — you need the courage to show it, and the technique to be able to do so, but if you don’t see it, then nothing else matters.

And the path to seeing what others don’t see is guarded by the dragon of artist’s aporia: the disorienting state of not knowing what you see. It is even more disorienting than the (original) aporia of intellectual puzzlement, because you’ve got to destabilise your normal sense of vision and shake off the comfortable illusion that what you see is reality. Only from this space you can hope to see something worth showing others.