“Blessed is he that visited this world in its fateful moments,

for gods invited him to their feast for a conversation.”

— Fyodor Tyutschev

These last days, in the aftermath of Election night, I found myself quoting these lines of a nineteenth century poem on more than one occasion — to others, and to myself. “Poems are rafts clutched at by men drowning in inadequate minds,” — Julian Jaynes wrote.

Overnight, we found ourselves in a completely new territory, in a different time-space — different from the day before, and quite different from what was expected, what was predictable. Not a single polls-aggregator out there, as successful as they were in all recent elections, got it right this time. Most of them predicted the opposite outcome with a huge deal of certainty, quite staggering in retrospect. But something happened — statistics failed, the illusion of stability was blown up, and now the air is filled with uncertainty. Scary for some, elating for others, but there seems to be a shared sense of disruption, discontinuity, a dramatic shift.

To my own surprise — because I definitely didn’t want this outcome — I experience this uncertainty as liberation. Not because I am lulling myself into false hopes of a successful presidency — quite the opposite; I think we are in for a rough ride, and we’ll need all the courage we can muster to face the challenges ahead. But there is more freedom, more intensity, even more joy in chaos and uncertainty than in stultifying stability and predictability (especially when these turned out to be illusory to begin with). More depends on each and every one of us. We — all of us — seem to have been invited to a conversation.

And, strangely enough, a meaningful conversation is beginning to emerge amidst all the fear, anger, confusion, grief, and gloating — the conversation that should have started long ago, but failed to do so.I did my best, over these last few days, to listen in to this emerging conversation as deeply as I could; I feel that it’s listening, rather than talking, that is needed now.

But at the same time, my thoughts kept returning to what I had planned for this week — the next essay in the “Art in the Age of Consciousness” series (this essay, in fact). Who would care, I thought, to read about art and consciousness in Ancient Greece this week? It must be as far from anyone’s urgent concerns as it gets… And wouldn’t this be some version of privileged escapism anyway: immersing oneself in the beauty of a golden age long since past, instead of being fully present to the unfolding fateful moment, or even busying myself with some immediate public actions?

But I started this series precisely because I believe its themes are urgently relevant right now, more than ever; and this belief hasn’t been shaken by the events of this week — if anything, it has only been strengthened. These events have shown us that we need to look at the present more deeply, beyond its surface-y manifestations. And our past is the depth of our present, and art is a way to perceive reality in a more profound way.

After all, the miracle of Greece — this awe-inspiring blossoming of art and philosophy — didn’t happen in the age of peace, security, and stability. It was the time of the Persian Wars; they were in the midst of a terrible struggle for survival. How was it possible? Gottfried Richter gives the following answer, in “Art and Human Consciousness”:

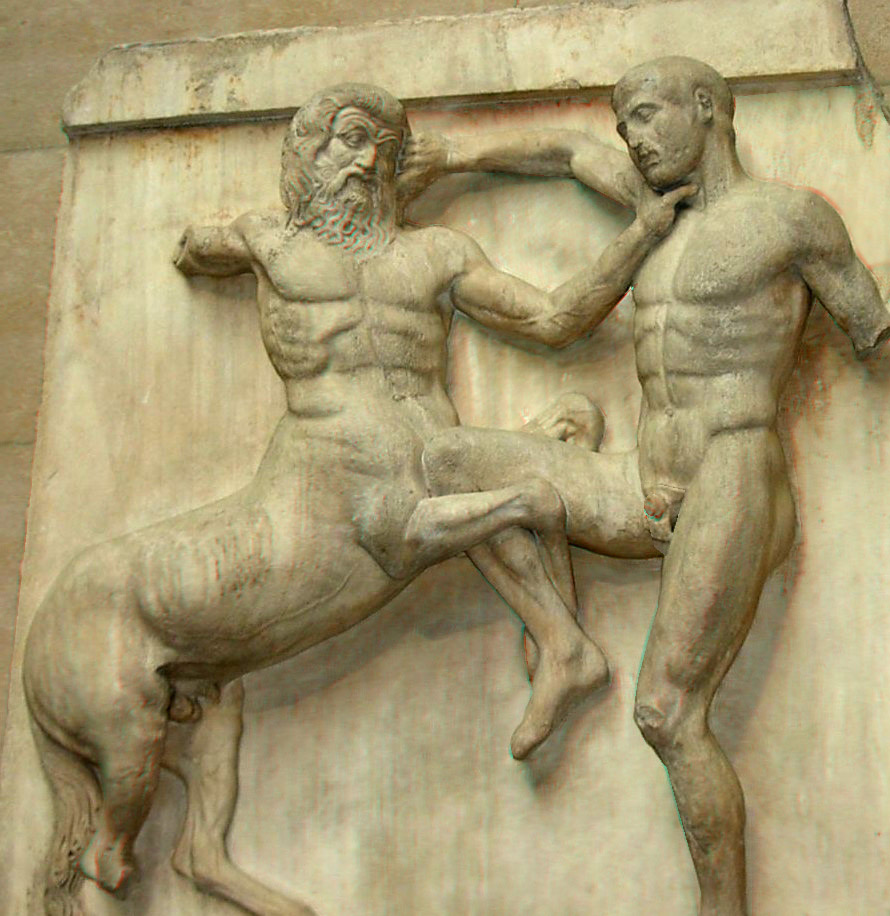

<…> it remains an enigma only so long as the attitude persists that art is something “alongside” of life. The truth is that the actual struggle for life during those decades, the original “battle of centaurs”, was not fought near Salamis, Marathon or Thermopylae at all but in the studios of the sculptors and on the building sites of the temples. That was where man experienced his victory over the centaurs and his consequent liberation again and again and where he could hear the soft melody of Apollo in its overwhelming beauty, clarity and harmony.

How does this “work”? I don’t pretend to know, but it does… The answer may never be expressible in words, but it can be experienced — in and through art itself. Art isn’t — and never has been — a luxury, a nice but unessential ornament of a comfortable, safe, privileged life. It is the life’s core, it’s basic necessity, felt most powerfully in hard times of danger, grief, and confusion. It’s not an accident that my penchant for quoting poetry was more needed this week than ever before. And it’s not an accident that many artists went to their studios to work in response to the events of this week, myself included. That is where the unity of life is restored, and inner peace and courage are regained, and liberation happens — amidst all anger, confusion, and fears.

Does it help, in the grand scheme of things? Yes, I think it does — if only because we are all connected, and inner peace, courage, and freedom are contagious. That’s why I decided to return to my theme of art and consciousness in Ancient Greece, however far from the present moment it might (falsely) seem.

Last week, I wrote about a huge shift in the evolution of consciousness which, according to Julian Jaynes, occurred right before the Greek culture blossomed. Before this shift, human beings experienced a very close and psychologically real relationship with their gods, and these gods directed human actions in all critical situations. According to Jaynes, this experience was created by a different, ancient, relationship between the two hemispheres of the brain. The left one (experienced as the acting “I” of a human), was directed by the right one (experienced as god or gods) — through voices and hallucinations.

And then, this ancient mode of consciousness was disrupted. At the same time, social structures collapsed, and chaos ensued. Whether or not these two disruptions conditioned or caused one another (in either direction), they were experienced as gods abandoning humans, and leaving them to their own (inadequate or non-existent) devices. And this, through long and painful struggles, engendered a new way of being in the world — the need for self-reliance, or rather, for reliance on one’s own mind. In a sense, it was a gain which we still cherish, the birth of thinking as we know it. In another sense, it was a painful loss — a further step in the process of internalisation of human beings, their deepening separation from life, with all its dark and deep mysteries, from the divine wisdom of nature.

Whether or not Jaynes’ hypothesis is correct in all its details, the very experience of disappearing gods, of their withdrawal from human life is beyond any doubt — because it is reflected in Greek poetry (in particular, in their great epics, Iliad and Odyssey). Jaynes writes:

It is even plausible that all this political havoc was the very challenge to which the great epics were a defiant response, and that the long narrative chants of the aoidoi from refugee camp to camp worked out into an eager unity with the cohesive past on the part of a newly nomadic people reaching at lost certainties. Poems are rafts clutched at by men drowning in inadequate minds. And this unique factor, this importance of poetry in a devastating social chaos, is the reason why Greek consciousness specifically fluoresces into that brilliant intellectual light which is still illuminating our world.

So these were the conditions for flourishing of Greek Art: the emergence of subjective consciousness, this inner mind-space separated from the outer, “objective”, world — and the memory of this shift preserved in poetic tradition. Art was their response to the disruptive disconnect between two sides of themselves, a way to transcend the separation between a human being and the divine nature. Here is how Gottfried Richter describes this concept:

<…> the human being who simply gives himself up to the workings of the forces of life remains dull, passionate, immoderate and akin to the animal. Whoever simply shoves these forces aside in favour of the spirit may gain clarity and a measure of morality, but he also becomes a withered intellectual and can never be sure that they will not come back to him some day and exact a terrible revenge. The man who really overcomes them and attains his freedom is the “muse-filled” or artistic human being who stands in the middle between the other two like Pythia, Apollo’s priestess, who sat over the pit out of which the dragon’s vapours rose and at the same time received inspiration from the divine forces coming down to her from above. This is man between the animal and God, where the breath of freedom blows that becomes one with a higher necessity.

This concept of art as the unifying force, as a way to transcend the duality of human nature and attain freedom, even the way to be fully human — it has been mostly lost in the course of history. Few people, I think, would agree nowadays that artists’ studios is where humanity’s real battles are being fought, won (and lost)?

But there is a reason we might need to bring this idea back into our collective consciousness now. We might be on the verge — or even in the process — of a new disruptive breakdown, perhaps even more turbulent than the one from which the modern consciousness once emerged. Except instead of disappearing gods, we now have failing rational minds. Because the rational mind, the subjective consciousness, the Ego — as it is experienced by modern humans (or at least most of them) — is obviously having a great deal of trouble grappling with the increasing complexity of the world, and there is a growing suspicion that the controlling, “executive” function of rational mind is an illusion, a dream, just another self-induced hallucination. Once again, we are drowning in inadequate minds, and the failures of our social institutions, the crumbling political systems might be just the “outer” reflection of this deeper phenomenon.

If so, the question is: can art save us again?