“Life is as infinitely great and profound as the immensity of the stars above us. One can only look at it through the narrow keyhole of one’s personal existence. But through it one perceives more than one can see. So above all one must keep the keyhole clean.” — Franz Kafka

My mind often returns to Kafka’s keyhole metaphor, because I believe that seeing — really, genuinely seeing — great paintings is a powerful way of defying this limitation of human condition. Our keyholes are so very different — shaped by the time we live in, cluttered or cleansed by personal experiences. An artist is someone who shares the view through their keyhole, so that a viewer can see more than their own keyhole would allow, and thus enrich and expand their experience of reality.

But there is an inherent paradox here, because a painting itself — being, as it is, a part of reality — is also being seen through the viewer’s keyhole, isn’t it? If there is a “mismatch”, a misalignment of the keyholes, then the viewer is unable to see what the painting has to show. It may take another artist, closer to the viewer’s own time and artistic sensibilities, to reopen this channel of communication, to revive a painting’s ability to show.

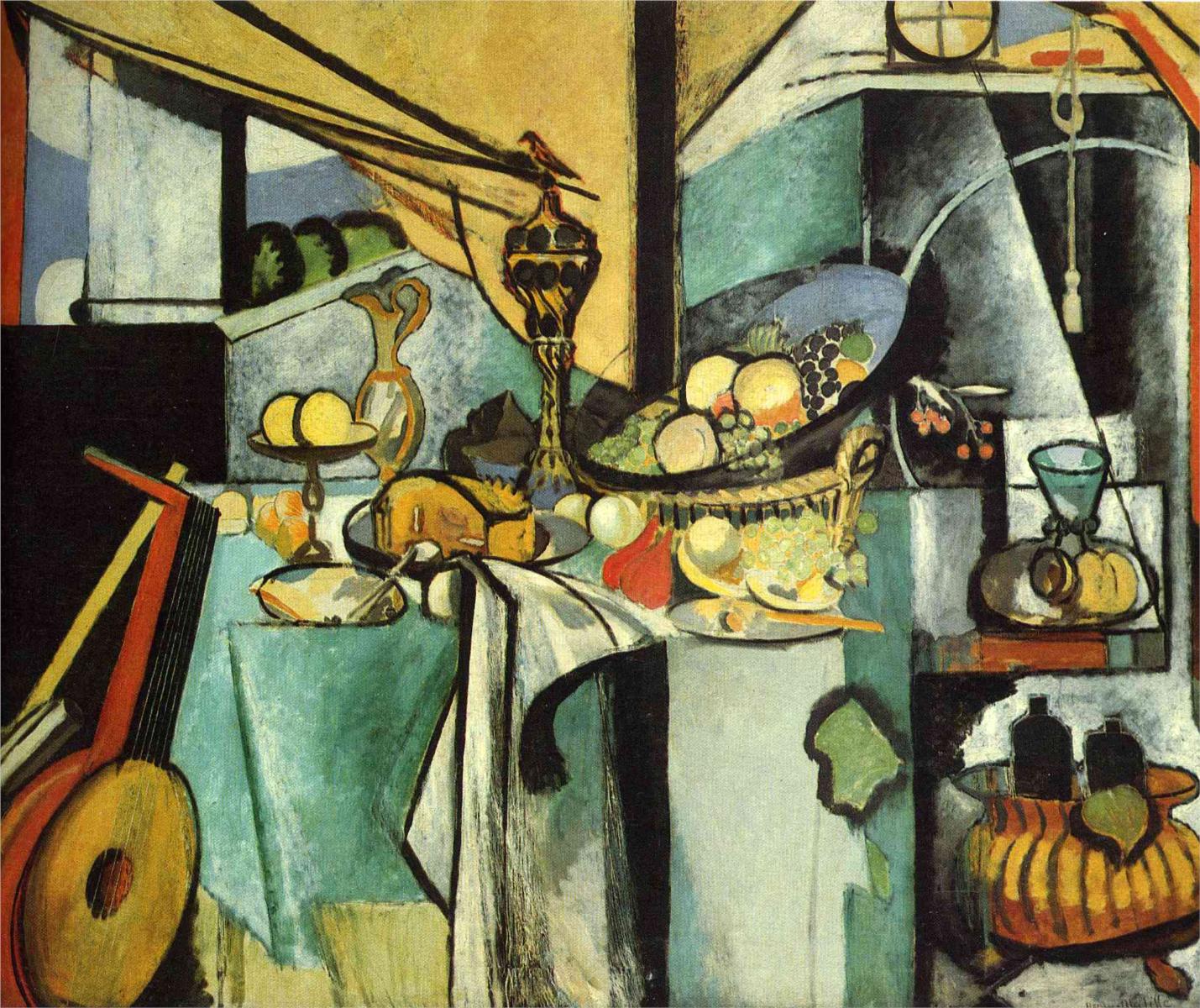

This, I believe, what Henri Matisse did in his 1915 remake of Jan Davidsz. de Heem 1640 painting, “Table of desserts”. Three years ago, I spent a couple of months studying these two paintings (and painting a triptych of still lifes in the process), and, looking back, I think it was one of the most significant breakthroughs in my own evolution as a painter — and, probably, as a human being, too. Returning to the keyhole metaphor, I think this experience might have re-shaped (or thoroughly cleansed) mine.

I was recently reminded of this experience by a conspiracy of two events. One was working on my course, “Learning how to learn from masters”. It made me think more deeply about the phenomenon of “painting study” (in a sense, that’s what Matisse does here). The other is reading a brilliant book, “Art and human consciousness” by Gottfried Richter. It showed me this remarkable encounter between Matisse and de Heem (and the resulting “meta-painting”) in a new light: not only as the pinnacle of a painting study, but also as an embodiment of the evolution of art (and consciousness) over the last four centuries.

So what is it that Matisse saw in de Heem’s “Table of desserts”, and what is it that he shows us in his remake?

His very first step is to reveal the inner abstract geometry of the original painting: two grand upward-looking triangles, overlapping over the focal area of the painting (the table of desserts itself), and all major vertical and horizontal divisions of the picture plane (horizontals are less prominent than verticals here).

This geometrical structure is right there in de Heem’s original, but it is concealed behind the magnificent and richly detailed flesh of subject matter, just like the skeleton is concealed by the body. This structure is the picture’s inner scaffolding — a means to the end of composing the painting. In Matisse, it (almost) transforms into the painting’s subject matter.

Discovering this structure, the skeleton of the painting, is the first step in any painting study: it uncovers the painting’s own idiosyncratic “grid”, much more helpful than any standard grid one could use to “copy” a painting. It also makes one see the painting in a new way, deeper and more meaningfully — so it is also something to pay attention to when just looking at a painting. But Matisse’s intention here goes beyond seeing and beyond (just) studying — into the realm of art, which (as Edgar Degas once said) is not about seeing, but about making others see.

This inner structure, once seen, draws the viewer’s attention to several “marginal” areas of the original — areas which might have gone unnoticed otherwise, especially because de Heem seems to go out of his way to draw our attention away from them, towards the focal area in the centre.

Near the top of the right-hand triangle, we notice a heap of books and a globe on the top of the cabinet. In the opposite corner, the left-hand grand triangle is supported by the edge of a lute. The books and the lute are somewhat out of place in the picture focused on desserts: the food for thought and soul has been moved to the corners and (almost) hidden, to give place to the food for body. Matisse makes the lute more salient in the painting by turning it towards the viewer, to reveal its strings, its essential structure — just like he reveals the inner structure of the whole painting.

Near the top of the right-hand triangle, we notice a heap of books and a globe on the top of the cabinet. In the opposite corner, the left-hand grand triangle is supported by the edge of a lute. The books and the lute are somewhat out of place in the picture focused on desserts: the food for thought and soul has been moved to the corners and (almost) hidden, to give place to the food for body. Matisse makes the lute more salient in the painting by turning it towards the viewer, to reveal its strings, its essential structure — just like he reveals the inner structure of the whole painting.

The lute (apparently, this same lute) and books used to be de Heem’s primary subject matter in his youth — and he painted them in a completely different, austere, monochrome style. It’s only later in life that he turned to more colourful, more decorative — and, from what we know, more fashionable and conventional — still lifes and flower arrangements. The lute and the books at the margins of this painting tells a life story, a story of conventional adulthood filled with nostalgia for the dreams of one’s youth.

But Matisse reveals even more. In de Heem’s original, the lute is directed upwards, towards a barely visible window, concealed by a curtain, and by the overall darkness of the area. Matisse draws away the curtain, so that we see a brightly lit landscape outside. The claustrophobic space of the original painting opens out into the whole wide world — but this world, this landscape is there in the original too, even though one needs a lot of patience and attention to see it.

Showing the strings of the lute and drawing away the curtain work as metaphorical representations of what Matisse does in this remake: revealing the essence of the painting, unveiling of hidden things, opening up what was closed.

Why would de Heem include something in the painting, and yet use all available pictorial means to draw the viewer’s attention away, to conceal them? And why would Matisse, three and a half centuries later, return to this painting to crack it open, to reveal de Heem’s secrets?

Obviously, I don’t know answers to these questions, but they are interesting ones to contemplate — and this contemplation itself, even if it doesn’t bring any definitive answers, is essential for understanding these paintings, and the evolution of art in the intervening centuries.

I will return to these questions next week.