Between painting and language: a quest for freedom

… but man, proud man,

drest in a little brief authority,

most ignorant of what he’s most assured,

his glassy essence…

William Shakespeare (“Measure for Measure”)

There are prisons that are invisible until you try to get out of them.

I spent about twenty years of my life studying languages and linguistics, but it was only when I returned to painting — full-time, with absolute commitment — that I came face to face with the independent life of language within myself. From an interesting object of research, from a useful tool for thinking and communication, it suddenly turned into a sparring partner, a foe, a mind parasite.

Only within the painting process did I realise how utterly unable I was to stop language from incessantly replaying its bits and pieces in my head in pseudo-random, loosely associated patterns — because it was the first time in my life I actually wanted it to stop.

Language is a hindrance for painting, because a painter needs to see beyond what is nameable, to switch off the familiarity of recognisable things around us: to see a thing is to forget its name. Painting is a bid for freedom from the constraints of language — and so I deliberately excluded it from the painting process. In return, it did its best to distract me — or was it to attract my attention back to itself?

Before that, the life of language in my head used to masquerade as thinking. And, occasionally, it was: studying and analysing vast amounts of linguistic data is remarkably (perhaps even uniquely) suited for language-based thinking. Perhaps languages like to look at themselves in the glassy essence of humans?

And in my leisure time, this inner stream pretended to be me (along the lines of Cartesian Cogito ergo sum): my thoughts, my feelings, my memories, my ideas, my self. I had never tried to find a pause button for it. And when I did, it turned out there was none.

I have learned since then this inability to will away the inner stream of language was not my personal “bug”, but a universal of human condition. Painters know it — and, quite often, resort to the easy solution of silencing the inner stream of language with audiobooks. Many people face this problem when they try to meditate, and it generally takes a lot of practice and discipline to access even brief moments of silence.

The life of language within us can be experienced in many different ways. Sometimes it stops on its own in times of danger, when all the brain’s resources are needed for survival, or in the zone, when they are fully focused on something else. Sometimes it goes underground, and stays unnoticed for a while. And it often attaches itself to our fresh wounds, painful memories, or overwhelming emotions.

Some of us are better at riding this stream than others. Some live their lives without ever seeing it as a problem. Still others channel it into great literature… But in one way or another, each of us gets a slice of this universal human condition, a shard of our shared glassy essence.

But why is it so impossibly hard to stop it, to will it away?

I looked for answers everywhere — in psychology, in philosophy, in spiritual literature. I learned a lot, but the question wouldn’t go away — whatever I read, it was all mostly about specific themes picked up by the stream of language (our fears, our anxiety, our desires, identity, melodramas of human relationships, etcetera, etcetera). But the thing is, when a theme is resolved, the stream of language doesn’t go away with it — it just picks up another one to play with, like a kitten does when you take away a toy it seems so fully engaged with.

The answer, I thought, must lie beyond these particulars — and, as it turns out, it was staring me in the face all this time.

Crawling between heaven and earth

We are such stuff dreams are made on.

William Shakespeare (“The Tempest”)

The radical idea that languages are living organisms crystallised into a linguistic theory by the end of the twentieth century, but it had been around for some time before that. Although this theory — the Leiden theory of language evolution — is very far from being the mainstream of linguistics, my life kept bringing me in touch with it, as though it was trying to get my attention. I even worked in Leiden for a while, with its founding father, Frederik Kortlandt, albeit on a completely different project. Paradoxically, it took painting for me to recognise the unsettling — perhaps even dangerous — truth of it.

In daily conversations, we use words to point to things or phenomena, to stand for them. It works most of the time, which makes it tempting to imagine that there are clear, definable differences between things a particular word can point to and those it cannot. The human mind wants to believe that when it says something, it knows what it is saying.

But it doesn’t: linguistic meanings are beyond the grasp of logic, beyond the mind’s urge to define everything. Socrates knew that — that’s why he claimed not to know anything and dedicated his life to pestering his fellow Athenians with questions about the meanings of words, in an attempt to bring them to realisation that nobody can know anything at all. All verbalised knowledge is constructed from ultimately unknowable building blocks.

See just how easily the meaning of know crosses any definable boundaries within the space of a single paragraph? This fluidity of meaning is not confined to particularly “difficult”, hard-to-define, words — it is an intrinsic quality of all linguistic meanings, including simple things like house or water. And as soon as any carefully defined scientific term makes its way into a natural language as a proper word, its meaning loses its seemingly solid boundaries, and becomes as fluid, dynamic, and undefinable as everything else in language. And if we turn to the meanings of more abstract linguistic units, like tenses (as in “Past Tense”) or voices (as in “Passive Voice”), things become completely hopeless — their meanings seem less accessible to the human mind and its logic than all mysteries of the universe.

And yet, and yet… not only do we know our native languages (so we speak and understand them as easily and organically as fish swim), but we learn them “by osmosis” as children, way before we can be formally “taught” anything. “Language acquisition” in childhood is not a transfer of knowledge from one mind to another — that would require definitions we don’t have. One cannot learn a language by learning what we know about that language — to achieve any level of proficiency, we need exposure to, and participation in, its living reality.

This leads to this inevitable conclusion: words, and other linguistic units, are capable of self-replication. They can copy themselves into a new human brain, and, as a result, the whole organism of language re-creates itself anew there. Ideally, the new brain has to be immersed in the life of the language as early as possible, while still growing. In an adult brain, the process of replication usually results in a very imperfect copy, a mutant strongly affected by whatever languages are already there. But either way, all that is needed for self-replication is for linguistic units to get expressed in speech, to be present in sound waves surrounding the new human to be “acquired” by the language.

The crucial point here is that self-replication is the defining feature of life, and the source of all evolution. The ability of linguistic units to replicate themselves means that languages are a special life form, semiotic (or “memetic”) organisms co-evolving in symbiosis with human hosts.

The hypothesis of symbiosis means that languages have been shaping not just the evolution of human consciousness, but our biological evolution itself. Indeed, if linguistic abilities — being a good biological host for a language — increased an organism’s chances of survival and procreation, then genes that favour such abilities had better chances of propagating through the species. And so, step by step, humans would have evolved to be more and more suitable biological hosts for languages, to provide a better and better neuroanatomical environment for their survival and procreation.

The humankind as we know it has evolved not only to survive and procreate, but also to provide optimal neural soil for this younger life form. We are not (as genetics teaches us) just survival machines for our genes, but also for our languages — while languages themselves are, arguably, survival machines for meanings. That’s what we are, then — unwitting intermediaries between genes and meanings. What should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven? — Hamlet asks Ophelia. And here is a simple answer: provide a living connection between the earth around them and the heaven within, and we do so by virtue of being, whether we want to or not.

The only matter we might have some say in is the quality of this connection.

Our networks of neurones are the stuff the meanings are made of, and they are the stuff our minds are made of — every single thought like a small tightly-knit company of tiny living creatures masquerading as knowledge for the sake of successful self-replication. But try to autopsy these creatures with logic, to reveal their anatomy — and the whole illusion of knowledge dissolves into thin air. We are such stuff dreams are made on.

Poetry: listening to the unsayable

Glücklich, die wissen, daß hinter allen

Sprachen das Unsägliche steht

(Happy are they who know that behind all

Languages lies the unsayable.)

Rainer Maria Rilke

The Leiden theory of language evolution hasn’t gained much traction in the field of linguistics, which — like all humanities — tends to be rather human-centric. It is understandably hard to shift the vantage point away from ourselves, and consider life from the perspective of another life form.

But if we do let go of the human-centric perspective for a moment, then the incessant stream of language in our minds appears perfectly natural: it is not about the human host at all, it is just the life of language. For patterns of neural excitations and inhibitions, the only way to survive is to constantly renew themselves — and this, for a human, feels like bits and pieces of language being replayed in their head.

What if our inability to stop this stream at will is what makes us into good survival machines for languages? What if this is a part of the whole symbiotic “deal”: we get to use the language for our own needs, and in return, it gets to live and play in our brains even when we don’t need it? Such an arrangement wouldn’t look too different from other instances of symbiosis found in nature. Language doesn’t care, perhaps, that its biological host takes this so personally — and which painful memories or fears are triggered in the process…

The question is, if we are bound to live in symbiosis with languages, is there a way to co-exist with them peacefully, in the spirit of true collaboration rather than futile resistance to the inevitable?

One of my early attempts to clear my head of language for the process of painting involved following David Allen’s advice and creating an external system of reminders for all the little things to do (so that my brain wouldn’t feel the need to remind me of them). Having spent some time designing and implementing this system, I went to my studio and picked up my brush, hoping for inner silence. No such luck: a language residing in my head — the English language on this occasion — went all Shakespearean on me, and shouted in my head:

My sovereign lord, bestow yourself with speed!

The French are bravely in their battle settled,

And will with all expedience march upon us!

I laughed through my frustration. In spite of the sheer absurdity of this unexpected request, there was a glimpse of collaboration there, a barely recognisable offer of peace.

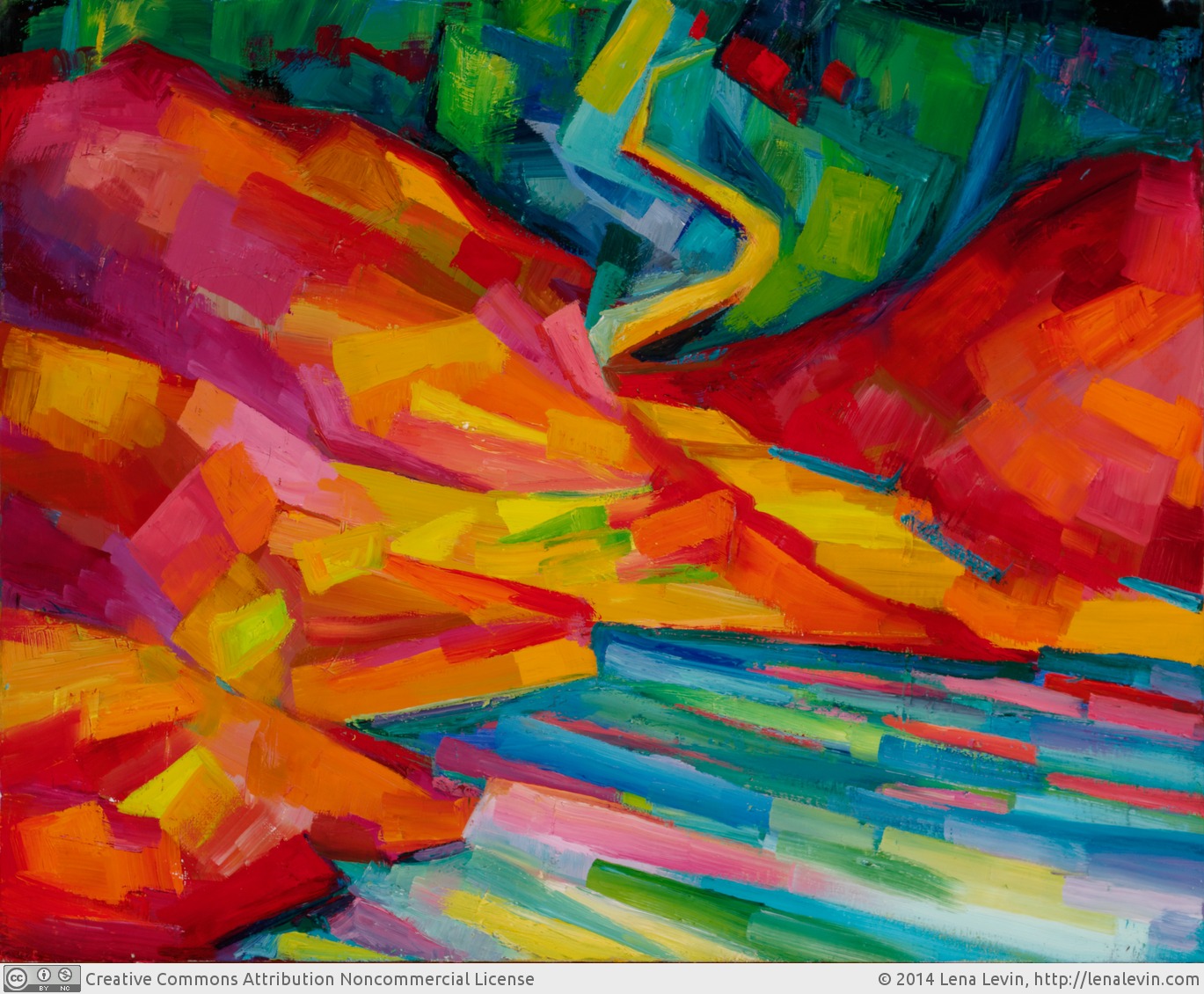

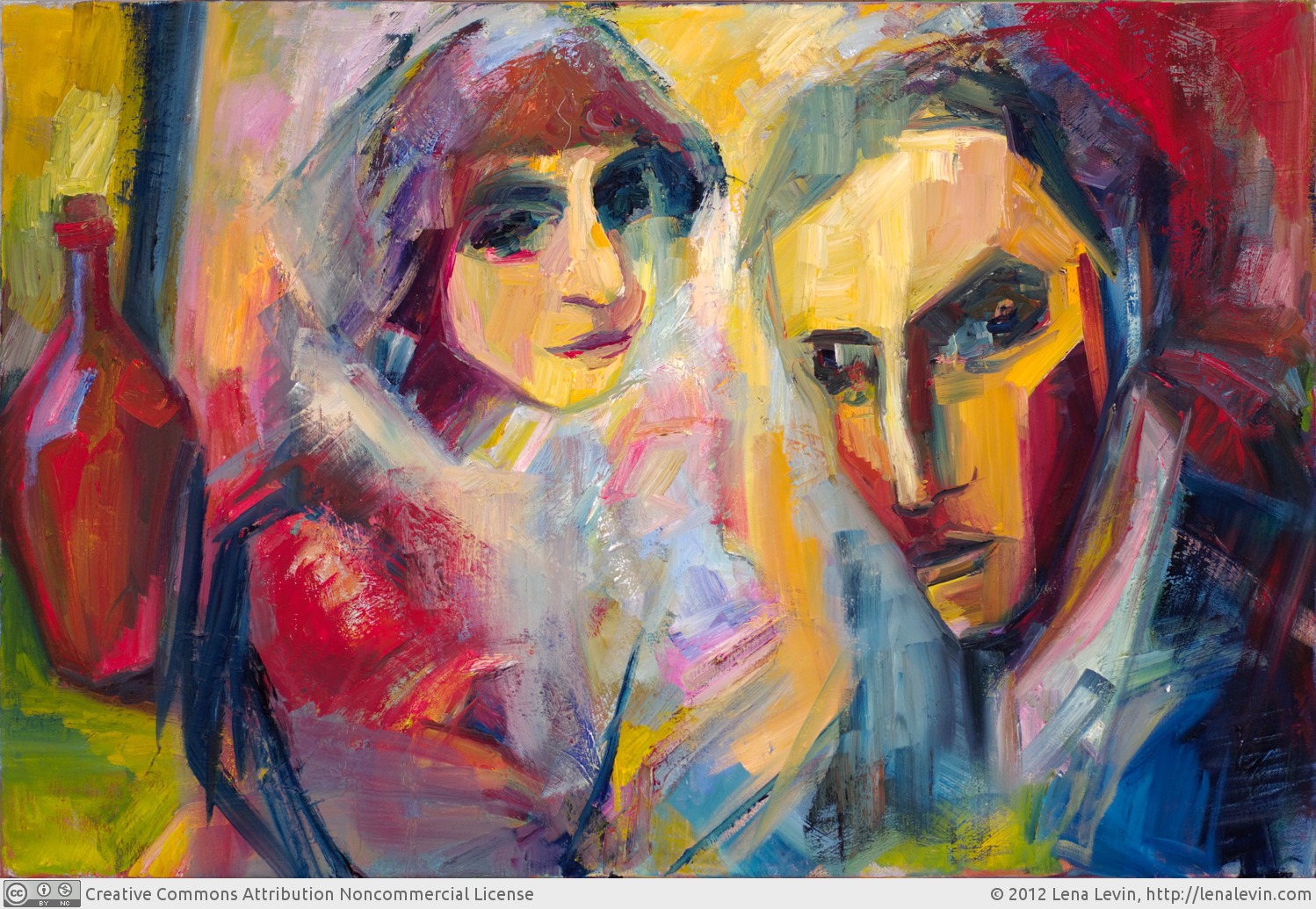

My head has always been full of poems, and they would occasionally float into the unfolding inner stream of language. This wasn’t random — the poems would emerge in connection with whatever I was painting, although the nature of this connection wasn’t always easy to discern. Rather then interfering with the process of painting, these poems — if they stayed with me — would imbue it with new layers of meaning, lend their inner music to paintings. After a while, I learned the knack of putting poems “on repeat” in my head, and listen to them inwardly while painting.

I stumbled upon this solution to my predicament accidentally — or to be more honest, it seemed accidental from my vantage point, from where I was at the time. Poetry — the process of poetry — is the highest, most sublime form of the human-language symbiosis we know. And I am beginning to think that therein lies a path to freedom, a key that can unlock the prison of the mind — not only for poets, but for us other mortals, too.

Great poetry looks like the ultimate mastery of language, but a poet experiences it rather as surrender: a poet is a servant of language, not its master. When a poem comes, all the poet can do is listen, with sustained attention — so as to be able to write it down. The experience is not of saying something, but rather of hearing something.

It’s the same with all art forms: mediocrity makes art, genius surrenders to Art. Mediocrity is focused on self-expression, genius listens to something larger than self, to Rilke’s unsayable behind all languages. In poetry, a language gets to express something more magic and profound than what is remotely possible in its ordinary daily life, something well beyond the abilities of rational human mind.

There is a strange similarity between the emergence of poems, as experienced by poets, and the inner stream of language, as experienced by all humans. In contrast to the ordinary, deliberate use of language for thinking and communication, the human being doesn’t feel in control of the incoming stream. It’s like the difference between taking a shower and being in the ocean — except a great poet is like a master surfer, while most of us can barely keep our heads above water.

But in the process of poetry, there is no self-identification with the stream of language; the poet is the listener, not the speaker. Although not always in these words exactly, but poets seem to recognise their language as a life form in its own right, and willingly sacrifice their minds to what it wants to express.

I am not a poet, so my path to this recognition was long and windy, a roundabout via the science of linguistics and the art of painting. But the key mental gesture needed for a peaceful symbiosis with language turned out to be the same: listening. Strange as it seems, but it is enough.