Throughout all beings extends one space, world inner space…

Rainer Maria Rilke

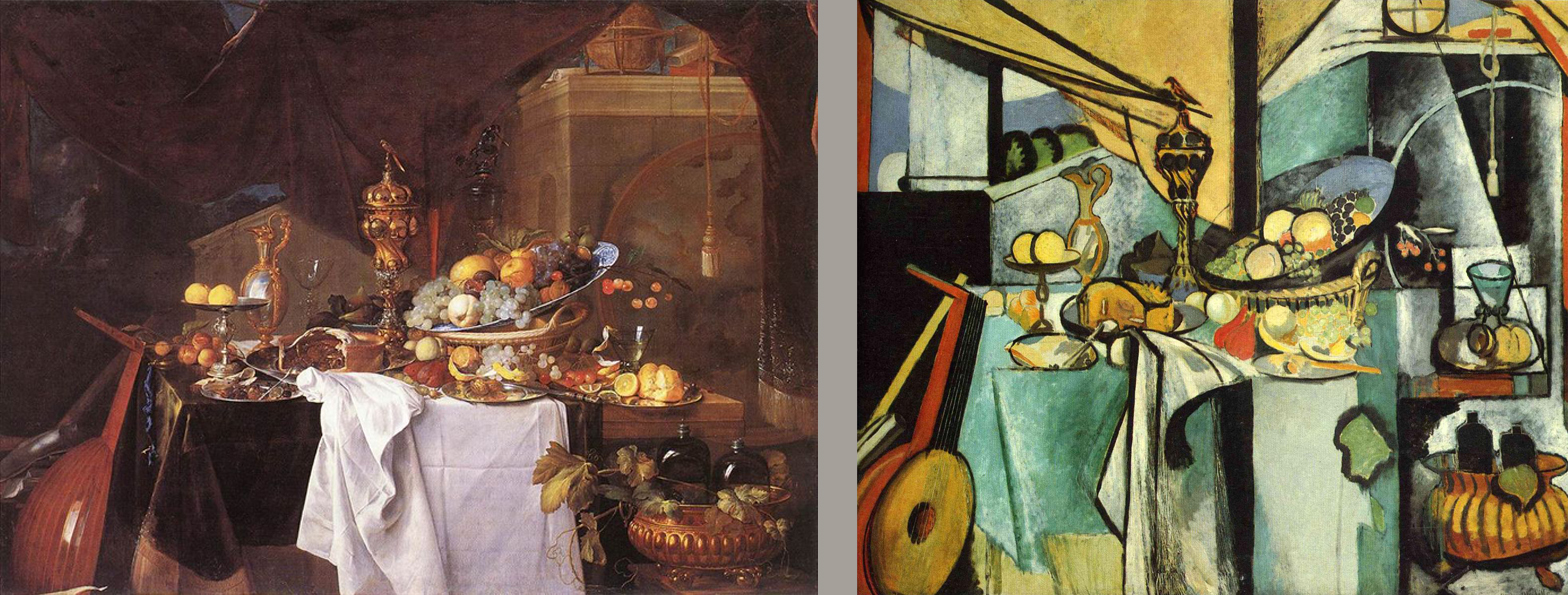

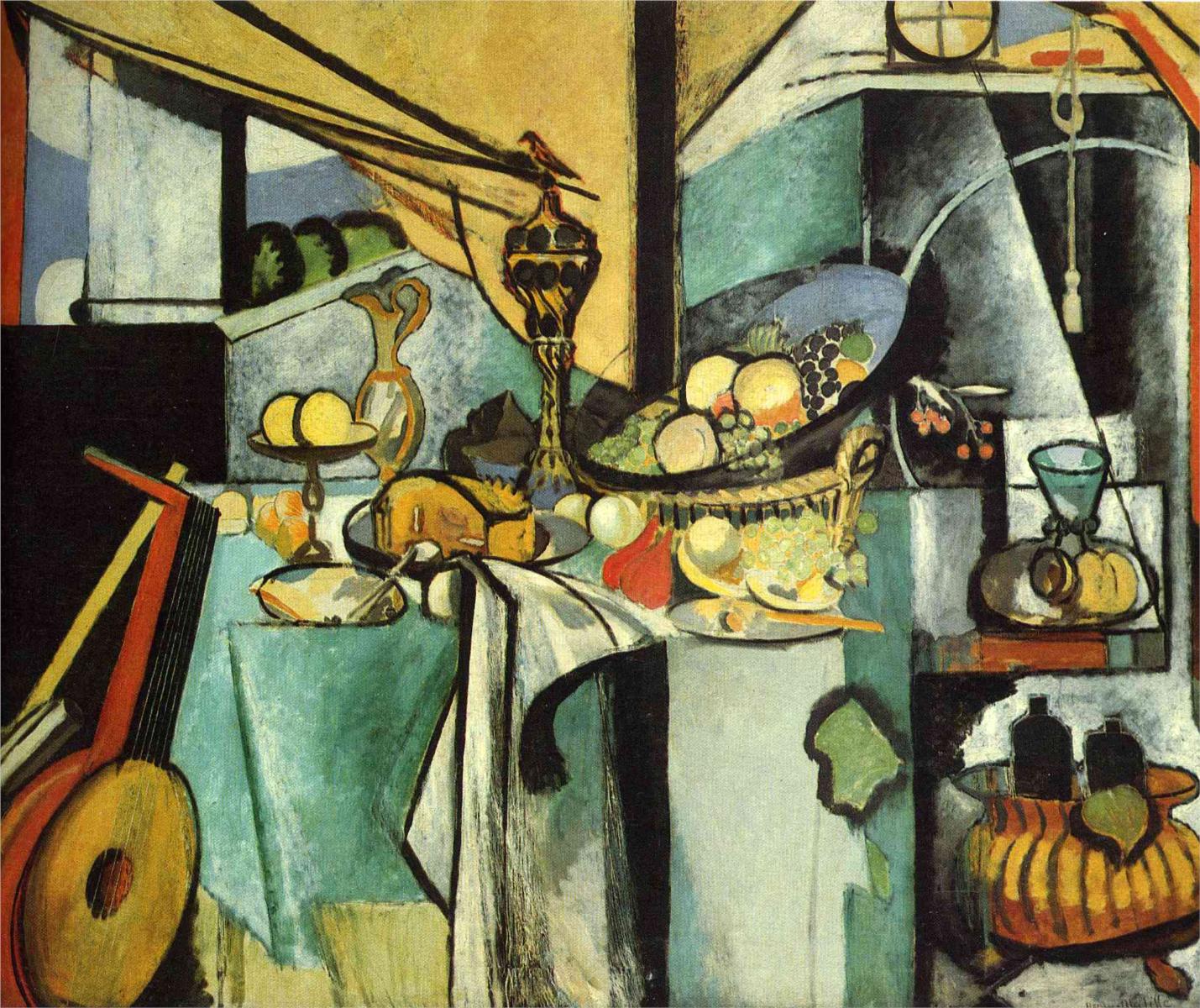

I wonder whether de Heem’s “A Table of Desserts” and Matisse’s remake will ever be exhibited side by side.

As it is, one resides in Paris, the other in New York, and it’s only in reproductions that we can look at both at the same time. And when we do, the first striking impression emerging from this comparison is time itself (or perhaps rather Time, with a capital T): one doesn’t need to know exact dates (nor pay attention to any details) to see immediately that these paintings come from different ages.

Wassily Kandinsky, in his book “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”, equates time with style. He writes:

Every artist, as child of his age, is impelled to express the spirit of his age (this is the element of style)— dictated by the period and particular country to which the artist belongs.

Time, for Kandinsky, is one of two subjective elements of artist’s inner need (the other one is “personality”). The third element is objective, and it’s both most essential and most mysterious of all. Kandinsky describes it as “the element of pure artistry, which is constant in all ages and among all nationalities”. In Kafka’s metaphor of perception as “keyhole”, the subjective elements of art are the keyhole, and the third is the objective reality we are trying to perceive.

The spirit of the age connects the artist to their contemporaries. It’s a natural “overlap” in their keyholes, their common language. It makes it easier to see what the artist has to show.

In de Heem’s time, Matisse’s “language” would be completely incomprehensible. A seventeenth century viewer wouldn’t have recognised anything at all in this painting. Most likely, it would appear to them as a meaningless noise of colours and lines. It would seem like a joke, and not a funny one at that, if somebody were to tell them that Matisse’s remake “reveals” anything “hidden” in de Heem’s painting (like I did last week).

What is it that would make Matisse’s version almost “invisible” to de Heem’s contemporaries?

Gottfried Richter, in his book “Art and Human Consciousness”, aptly calls this change in painting “the shattering of space”.

Perspective disappears: there is no (illusion of) third dimension in Matisse’s remake. De Heem’s carefully created illusion of volume is replaced with flat colour areas. His multiple layers of distance all collapse onto the single picture plane. There is no difference between “near” and “far” anymore.

The pictorial space itself disappears as a separate space, enclosed within the edges of the picture plane.

De Heem builds this enclosure with two pictorial means. First, there are two large structural triangles, whose upper apexes lie on the upper edge of the painting. They are fully within the picture plane, and the still life exists within them. Secondly, there is a simple and clear division of painting into dark and light areas: a well-lit focal area is surrounded by darkness, which separates the still life from the outer world.

Matisse changes both. He moves the structural triangles upward: their upper apexes are now above the edge of the painting. This “opens” the composition and dissolves the conventional boundary between the painting and the world outside. And the dark and light areas are now scattered throughout the painting in a complex, “illogical” pattern. The illusion of closed pictorial space disappears completely.

These changes may seem purely formal, but the difference between “form” and “meaning” makes little (if any) sense in painting. The “formal” shattering of space is an expression of an inner experience. It couldn’t have happened in a painting without being experienced within.

To name this inner experience, Gottfried Richter resorts to this line from Rilke:

Throughout all beings extends one space, world inner space…

Here is how he explains it:

In the first part of the twentieth century, the “ideal of painting things and people the way they look, or appear” is being replaced with the ideal of painting things and people the way they are. The world seen “from the outside” gives way to the view from within the “world inner space”. This is what shows up in paintings as the shattering of comfortably familiar three-dimensional space.

And this is what we see when we look at these two paintings side by side.

With this in mind, I can finally return to two questions posed in the first part of this essay:

Why would de Heem include something in the painting, and yet use all available pictorial means to draw the viewer’s attention away, to conceal them? And why would Matisse, more than three centuries later, return to this painting to crack it open, to reveal de Heem’s secrets?

But is it de Heem who did all the “hiding”, or is it the intervening time?

If Matisse’s remake would have been incomprehensible to seventeenth-century viewers, the reverse effect is possible as well. The language of painting, and our inner experience of reality, have shifted. This alone may “conceal” some parts of de Heem’s original from the modern viewer. They could have been more visible to contemporary viewers, just like it was easier for Shakespeare’s contemporaries to “get” his jokes.

But even if we take this into account, the contrast between what’s shown and what’s hidden, between the intended focus of attention and the “out of focus” areas, is still there in de Heem’s original. And this tension is, I believe, at the heart of the inner experience expressed by this painting.

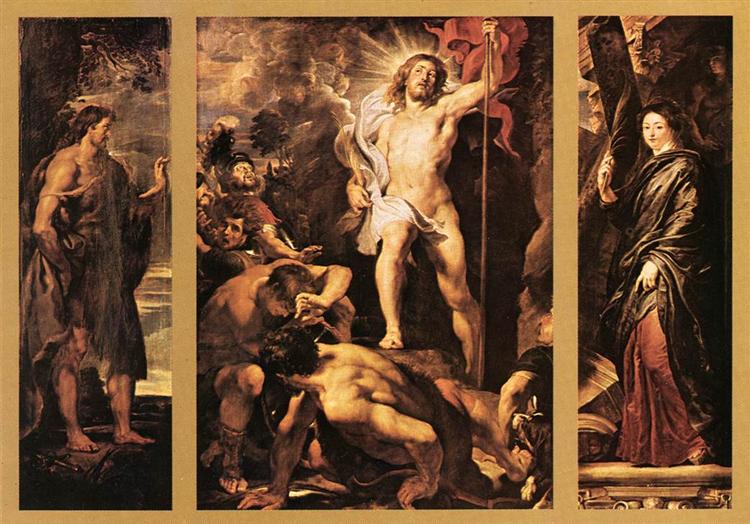

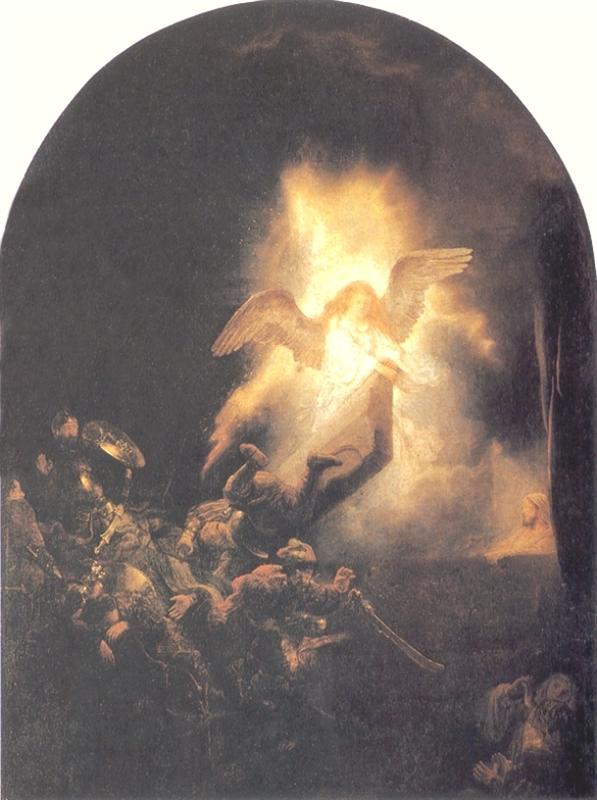

As Kandinsky tells us, “every artist, as child of his age, is impelled to express the spirit of his age”. But Jan Davidsz. de Heem was a child of two ages. There were two, very different, Zeitgeists he must have been impelled to express. (Almost) without exaggeration, he found himself on a huge rift in time and space, or at least in Zeitgeist.

He was born right into the Dutch War of Independence from Spain (the Eighty-Years War), which split the previously unified area into the Dutch Republic and Flemish provinces (which remained under the rule of Spanish kings). It was also the time of Reformation, which split the society into two warring parties of Catholics and Protestants. In art, this rift made itself visible as the contrast between the Dutch “Golden Age”, with its austerity and precision, and the more colourful, refined and decorative style of Flemish Baroque.

De Heem stands apart from most artists of the time in that the rift was going right through him, through his inner world. He lived both in the independent Dutch Republic (in Utrecht and Leiden), and in Antwerp, under the Spanish rule. And, more importantly, he painted in two quite different styles, as though there were two different painters in him — one from the Dutch Golden Age, the other, from the age of Flemish Baroque.

Most of his known paintings clearly belong to one or the other side of the divide. But this one, chosen by Matisse, is special: the rift goes right through the painting. This inner rift is the subject matter of this painting, the experience it shares.

This, I believe, is what is expressed in the tension between “public”, focal and “private”, concealed areas of the painting: the inner experience of disruption, a rift between two halves of one’s self coinciding with a rift in the spirit of the age. In a sense, it is the beginning of the same “shattering of space” that manifested itself more clearly and overtly in the twentieth century.

And it is this affinity that must have attracted Matisse to this painting. He doesn’t paint a still life here — he wouldn’t have needed de Heem for that. What he paints is a painting, this painting — not as it looks, or appears, but as it is — from the shared inner space. That’s why his remake reveals what is hidden in the original.