From “Why painting?” series

I recently read on “Brain Pickings” that, according to Nietzsche, life would be a mistake without music. When not yet fourteen, he wrote:

Can painting do something similar?

A remarkable feature of our age is that we have institutions specifically intended for viewing paintings — museums and public art galleries. Historically, this is a very recent phenomenon: it began to emerge in the eighteenth century (more or less, with nationalisation of royal collections). Before that, paintings belonged in spaces created for other functions. To put it in other words, they participated in creating these spaces, and, at first, they couldn’t even ever leave the walls of these spaces — from pre-historic caves to medieval cathedrals.

The rise of this new phenomenon of museum — a place where people go to just to see paintings, “for their own sake” — reflects the idea that they can do something important for you (or to you) on their own, just as a result of you looking at them. In a very material, “outer” sense, the museum replaced the cathedral — and the implied promise is that it can also replace it in the spiritual, inner realm.

It is barely possible to put this promise in words — words can but point to an experience: if you haven’t experienced it, they will seem to point to nothingness. Yet this very difficulty hints at the fundamental promise of painting: at its best, it communicates experiences in a way more direct and “primal” than words — in a way similar to music, just engaging another of our five senses. What paintings do is show, and this act of showing — if met by the act of seeing — connects the inner space of the artist with the inner space of the viewer. It makes the invisible visible. And if the connection happens, it opens your mind and heart to new experiences and/or brings the light of awareness and compassion to your own experiences — and this can heal the soul, expand the consciousness, elevate the spirit.

Does the modern world need that? I’d say, yes, it probably does. But does the museum keep the implied promise? Do we — can we — “get” what we come for?

There is no easy answer to this question.

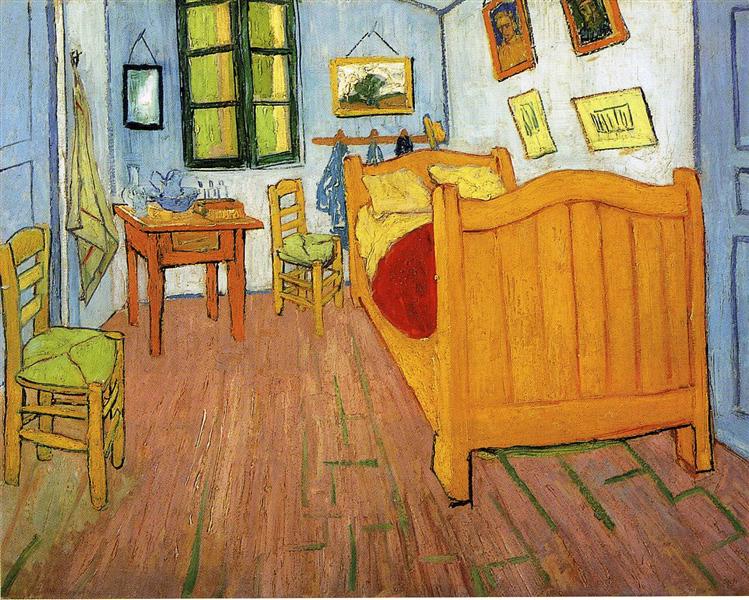

On the one hand, people keep going to museums: many museums are overcrowded, and it is often hard to even get to a temporary exhibition. Just recently, we visited a Van Gogh exhibition in Chicago (which brought together three versions of his bedroom painting from three museums) on a Friday, and decided to return the next day again — but encountered a very long and very slowly-moving queue. It was nearly impossible to get in on Saturday (and the exhibition was overcrowded even on Friday). It seems natural to conclude that one has to feel the need for seeing great paintings — and to get something essential from seeing them — to brave such obstacles (and this doesn’t even take into account all the people traveling across the world to visit great museums).

But if one looks closer at people while already in the rooms of these museums and galleries, it becomes difficult not to doubt this optimistic conclusion. More than a century ago, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to his wife, in one of his “Letters on Cézanne”:

Human beings, how they play with everything. How blindly they misuse what has never been looked at, never experienced, distract themselves by displacing all that has been immeasurably gathered together. One cannot expect that a time that is capable of gratifying aesthetic requirements of this order should be able to admire Cézanne and grasp anything of his devotion and hidden splendor. <…> And the women, how beautiful they appear to themselves as they pass by; they recall that just a little while ago they saw their reflections in the glass doors as they stepped in, with complete satisfaction, and now, with their mirror image in mind, they plant themselves for a moment, without looking, next to one of those touchingly tentative portraits of Madame Cézanne, so as to exploit the hideousness of this painting for a comparison which they believe is so favorable to themselves. ”

And he didn’t even have to witness the modern custom of briefly stopping with one’s back to a self-portrait of Van Gogh’s to make a “selfie”, before running to the next room — or out of the museum and to the next tourist attraction… And even when someone does actually turn their eyes towards a painting, this time is indeed rarely long enough to see, to perceive what the painting expresses, to do one’s part in establishing the connection that could have been healing and elevating — but never occurred.

Witnessing this, again and again, tempts one to put the responsibility fully — as Rilke does — on the shoulders of human beings, who do visit museums and exhibitions, but are barely present there. As an art form, painting that does ask human beings to pay attention for an extended period of time, or rather — waits for them to pay that attention. Unless this attention is willingly given, nothing can happen. And painting has a harder time getting that attention than music, because it is so silent — it’s much easier not to see than not to hear. And all too often, it seems that people come to museums, but do not see.

But in their recent book, “Art as Therapy”, Alain de Bottom and John Armstrong suggest a different, more compassionate, perspective: people come to museums attracted by the promise of art, but leave them dissatisfied and frustrated, not only because they don’t really know how to look, or even what exactly they are looking for there. Another reason is that museums don’t really help, and occasionally even hinder the possibility of this real connection (both because of how their collections are compiled and organised, and of how paintings are presented and introduced to the viewer). In other words, people need paintings, but the very concept of museum has to be re-thought for this need to be satisfied.

Indeed, with few exceptions, the context of museum doesn’t allow any one painting to create a space needed for the connection to happen. There are just too many of them, and they were never supposed to “work” together — and their very multitude almost invites the visitor to see as many of them as possible, without giving enough attention to any single one. It’s almost as though a multitude of symphonies were performed at the same time in the same concert hall — a couple of minutes for one, then a couple of minutes for the next one, and so on. I remember one particularly painful experience in an Italian provincial museum, with a dozen of rooms are filled with Madonnas gathered from defunct churches across the countryside. Each of them once contributed to creation of a sacred space, and some of them were quite brilliant paintings in their own right — but the context completely changed the experience of viewing them, and there is only so much an individual human being can do to get detached enough from this context.

Still, this is the only thing one can do for now — as an individual human being not directly involved in museum-related work. All in all, museums do their best to make the best paintings in the world accessible for anyone to see, and the best one can do is to take responsibility for one’s own part in the process of connection. In other words, if a painting isn’t given enough room to create its own space, this space has to be “created” by the viewer — with attention, patience, and time. And the mental skills needed for this are actually quite valuable outside museums, too — these, after all, are the same skills that are needed for being present, here and now, for one’s own life.

There are, however, deeper contradictions inherent in the phenomenon of museum, which, I believe, stretch beyond their walls and, somewhat paradoxically, undermine the role paintings of paintings in the modern life. I will return to this topic in the next essay of this series, next Saturday.

Previous posts from the “Why painting?” series

If you would like to be notified about further posts, please subscribe using the form on the left.