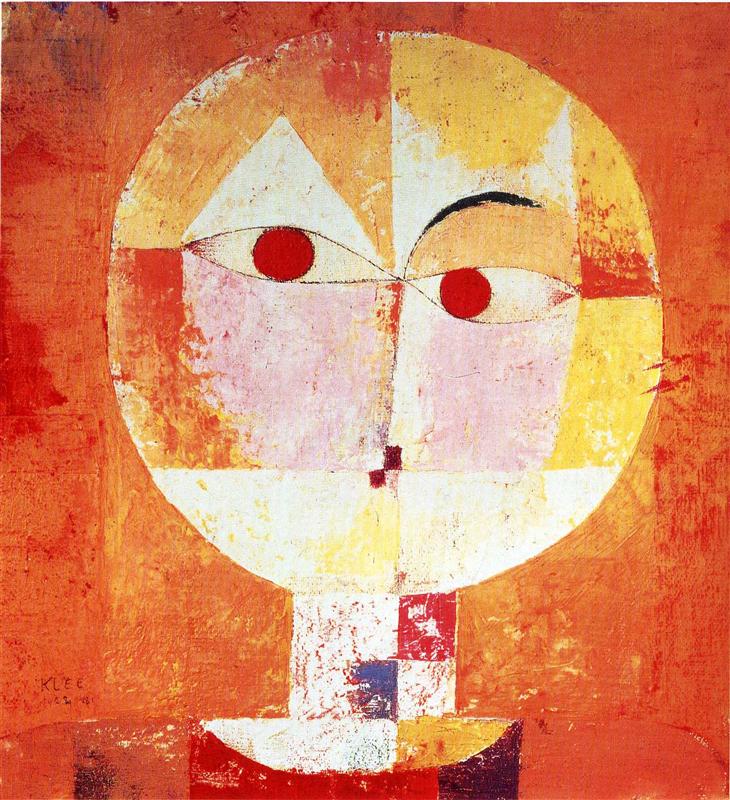

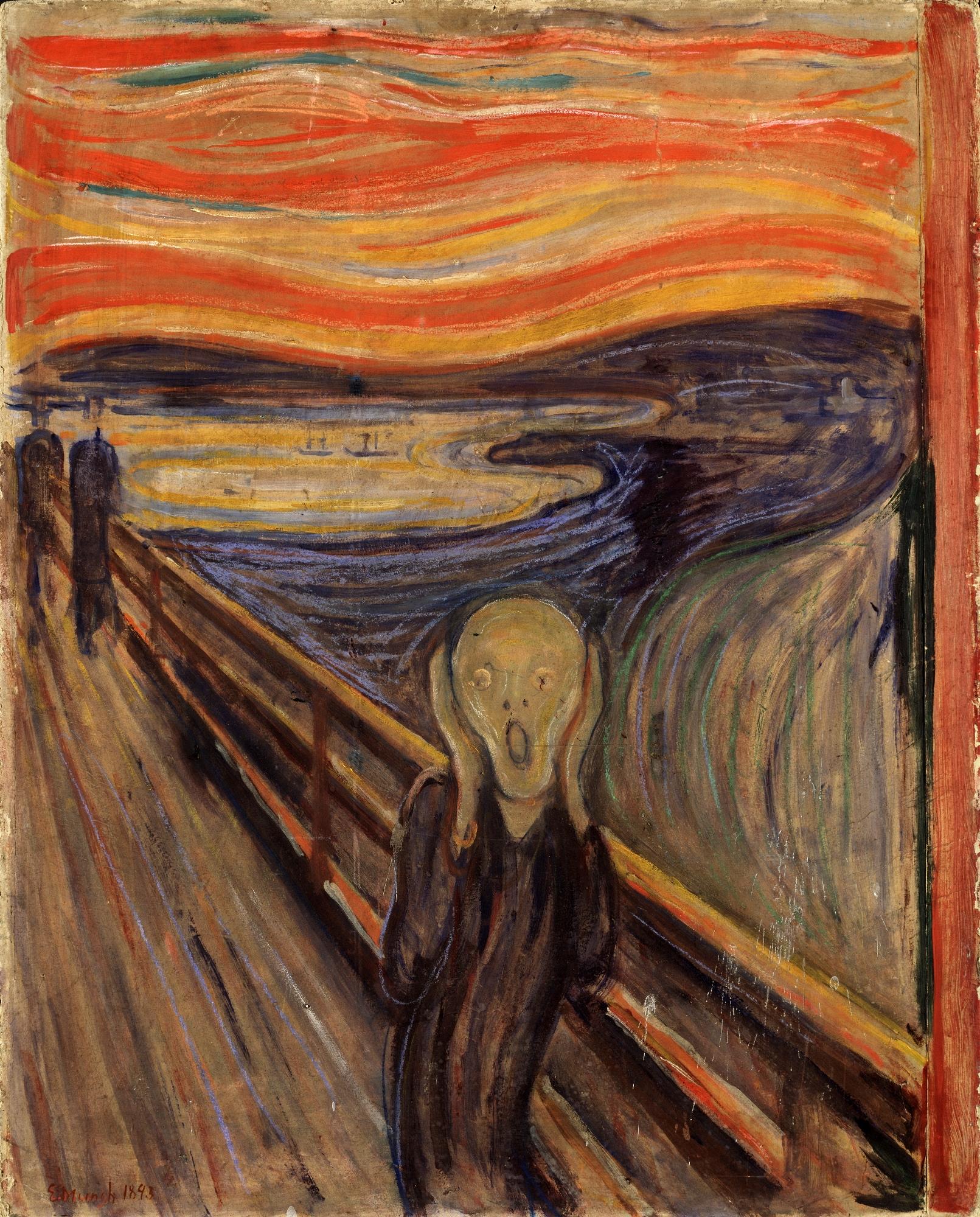

From “Why painting?” series

I had envisioned and announced the “Why painting” series of essays on this blog, but when it came to actual writing, I found myself stuck, deeply and, as it seemed, hopelessly.

It took me some time to see clearly that there were two huge stumbling blocks, which I was trying to avoid writing about, or even noticing. No wonder I felt stuck — if there are two elephants in the room, not much space is left for anything else. And as with any elephant in the room, the only way out is through… (there is no elegance in mixing these metaphors, but I don’t feel too elegant right now anyway). So I decided to start with the elephants, if only to clear the pathway to what I actually want to tell you.

The first elephant is my own inner need to paint.

It makes no sense to contemplate a question if you know the answer in advance, and aren’t ready to accept any other — but my inner need to paint wouldn’t allow me to accept that there is no place for painting in the modern world. Indeed, everything I was trying to write seemed to be just rushing impatiently through all questions and possible viewpoints, and onwards, towards this ready-made answer, as though in an attempt to shout out as soon as possible: yes, of course, sure, there is a need for painting in the world!

Questioning this amounts to undermining the very heart of my life; on some level, it feels like a suicide attempt. So does it mean that I am unable to address such questions, at least not objectively? I don’t know, but here is what makes it possible for me to try.

First, the inner need to paint will always be an essential part of any answer, because it is a part of this world — and I am only one of the many, many people who experience it. No “objective” answer can be complete without taking this into account.

Secondly, there is a wisdom and lightness in letting go — which doesn’t necessarily mean losing; in fact, we all know that sometimes letting go is the only way not to lose. And so I have to let go of the fear of life without painting — if this is the only way to face these questions (which won’t just go away because I am afraid of them). As Hamlet would probably say, readiness is all.

The second elephant’s name is “money”, and it stands for the money’s uncanny ability to insinuate itself into life as the ultimate measure of “value”.

Just imagine — just for the sake of argument — a society where the painting profession is, by some miracle, as secure and well-paying as, say, engineering and medicine are now — so that parents nudge their children to study painting as much as possible for the sake of a successful career — in this alternative reality, the need for painting would hardly be questioned (at least not with such regularity).

There is an obvious sense in which this elephant is a delusion, a chimera: we all know that money is not the only, and even not a very accurate, measure of value; as the things stand now, “money” and “value” are fundamentally misaligned at all imaginable levels.

And yet this elephant wouldn’t just dissolve into thin air, like an honest chimera is supposed to do when you look at it closely, and I believe there are at least two reasons for that.

One lies in the simple fact that paintings are objects — by their very nature, they are more thing-y than the products of many other creative processes — much more thing-like than poems, symphonies, or ideas. And the more thing-like something is, the more forcefully it “triggers” the idea of money as its “true value” in our minds: it seems much more natural, unavoidable even, to equate the price of a painting with its “value” than the price of a book with the “value” of a novel contained in it.

And the other reason — as far as I see it, at least — is the connection between human dignity and self-reliance. Self-reliance implies making a living, and making paintings is by far not the best way to achieve this. Not that it is impossible, just statistically very unlikely. The vast majority of painters have to rely on alternative ways of making a living, which may but need not be related to painting (like teaching in art schools, commercial illustration, or graphic design). By the way, painters are certainly not alone in this — for example, scientists are also rarely paid just for trying to solve fundamental mysteries of the universe. To make a living, they, too, have to teach and/or do some more commercialised research. And yet, my impression — from having lived in both worlds — is that this situation is more emotionally painful for artists than for scientists: somehow, it feels like a more immediate danger to their dignity and “status”. It may be because of the thing-like quality of paintings I mentioned above, or because of the “unlicensed” nature of being an artist (after all, you don’t need a Ph.D. for that), which seems to blur the boundary between “hobby” and “vocation”, and thus undermines the status of their work.

To sum up, facing my two elephants seems to have raised three topics for discussion:

- The inner need to paint, and how to deal with it in the modern world.

- Painting as “things”, and whether these things are useless or necessary (or both).

- A painter’s role in the world, and the problem of self-reliance.

As it happens, all three have been there in my plans all along, so the elephants turned out to be not so scary as they seemed (and I am sure there is a lesson in that…). But I will have to address them one at a time, in the future posts of this series (if you don’t want to miss them, please subscribe using the form on the left).

But before I conclude this “interim” post, there is one more thing to clarify. The question we really need to face is not about one painter’s needs and fears, and not about the monetary issues (in any forms and guises). It’s about whether painting, as an art form, still has its own role to play in the evolution of human consciousness.

And this is a real question, with a very real possibility of both positive and negative answers, because — as far as we can know the history of humankind — there was a time where painting didn’t exist as a “stand-alone” art form at all, and then there has been a time when its role was essential. Historically speaking, this latter stage began not so long ago (just a few centuries), and the question is, whether this moment, here and now, is still within this epoch, and what the future calls for.

I don’t promise any definitive answers — I may never know them — but now that my elephants are tamed, I can at least contemplate this question fully and openly.