This is the first post in In Studio in Masters series, fully dedicated to in-depth studies of painting masterpieces.

This is how I keep learning to paint myself, and my hope is that this series will encourage you to do such studies, too — because there is no more powerful way towards understanding painting and mastering this art. Short of that (and just in case you do not paint yourself, but just love painting), this series is intended to help you to see paintings more deeply, to connect with them in a more meaningful way.

Why have I chosen this still life by Paul Cézanne for the first “case study” in this series?

Alan Watts writes in “Become What You Are”, in the chapter entitled “What is reality?”:

“Some time ago a group of people were sitting in a restaurant, and one of them asked the others to say what they meant by Reality. There was much vague discussion, much talk of metaphysics and psychology, but one of those present, when asked his opinion, simply shrugged his shoulders and pointed at the saltshaker.”

This very gesture — This is Reality — seems to me to be the only valid reason to paint a still life; apart, of course, of the sheer enjoyment of the process. But even if you are “just” enjoying the process, this assumption — that this is reality — is always there in the back of your mind. In a sense, you become one with this particular manifestation of reality.

Still life is a tricky thing. On the one hand, it is probably the easiest of painting genres: if one is just beginning, a still life is probably what one would start with. No frustrating drawing problems of painting nudes; no braving the elements and dealing with ever-changing light to paint a landscape from nature. Just throw together some objects, and paint away. But on the other hand, it can be the hardest one:

How do you make an apple meaningful? How do you communicate a feeling with an apple?

Paul Cézanne is an absolute, unsurpassed master of this: his work points at apples (or other fruit, or simple household objects) in a way that says: This is reality.

This is a powerful, dazzling gesture. But how does he achieve it? Where does this sensation of being shown the reality, nay, more than that: deeply connected to the reality, come from? This was the core question of this painting study.

I must admit at this point that, at some level, I had known the answers I am going to share even before I began this study. But to know them “in general” and to let them embed themselves somewhere in the depth of your mind-body system by following the master’s footsteps — these are two quite different things. And the latter is a never ending process.

So don’t just “read” my answers — go back to the painting, and see them, feel them, let them become part of you. The only thing I can give you here are hints on what to pay attention to.

With this qualification, let’s me go ahead with my answers.

First of all, the pictorial space is organized as a kind of temple, a shrine for still life objects, making them — as it were — the God of this painting’s idolatry. This temple-like architecture is created by multiple overlapping geometrical shapes — triangles, circles, rectangles.

How to see this structure?

Remember these puzzles where you are supposed to find objects hidden in a picture? That’s the same process, except you are not looking for objects, but for geometrical shapes, starting with the biggest ones. Please find as many as you can — and post your results in the comments section!

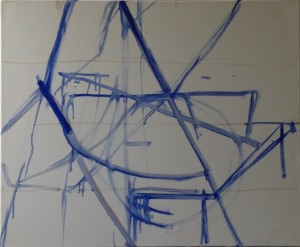

To help you get started, I am including the first “in-progress” shot of my study (By the way, notice that I don’t really use any “grids” or measurements which would allow me to place all objects exactly where they should be. Such grids may help you make a close copy more easily, but they will never tell you why the objects are where they are; they may actually prevent you from seeing the inner “logic” of the painting. That’s why I always start with major construction lines, not with a rectangular grid. Here, as you can see, there are just three horizontal lines for orientation)

An additional hint: a single geometric figure can “use” edges of different objects, and its lines are occasionally “lost” and then found again.

This hint brings me to my second answer: interconnectivity. There is not a single line, not a single edge between brushstrokes that wouldn’t be somehow connected with something else. Not even a single decorative element on the drapery is placed randomly, independently of still life objects or construction lines.

Just like with the geometrical figures, the more you study the painting, the more you see that within this reality, nothing is random. And if something seems random or arbitrary, it just means you haven’t found the connection yet.

And finally, the big elephant in the room: colour. The problem is, one cannot really see colour properly in reproduction (and I had to work from a reproduction for this study). To see what I mean, compare this reproduction of the same painting (from Artsy.net) with the one I posed above:

Yet even with these limitations, one can see (or at least guess) that the painting’s colour harmony is almost ideally balanced and self-contained — there is no dominant colour which would call for something outside the painting to complement it.

To see what I mean, compare Cézanne’s painting with this still life by Van Gogh, where the colour harmony is shifted towards yellows and blues. As a result, the viewer’s interpretation of the painting is bound to invoke their knowledge that there is more red in the outside world than in this painting.

Perhaps nobody can describe this quality of equilibrium in colour harmony better than Rilke did in his letters on Cézanne:

“When I made this remark, that there is nothing actually gray in these pictures <…>, Miss Vollmoeller pointed out to me how, standing among them, one feels a soft and mild gray emanating from them as an atmosphere, and we agreed that the inner equilibrium of Cézanne’s colors, which never stand out or obtrude, evokes this calm, almost velvetlike air which is surely not easily introduced into the hollow inhospitality of the Grand Palais. Although one of his idiosyncrasies is to use pure chrome yellow and burning lacquer red in his lemons and apples, he knows how to contain their loudness within the picture: cast into a listening blue, as if into an ear, it receives a silent response from within, so that no one outside needs to think himself addressed or accosted. ”

To conclude, here is an intermediate stage of my own painting study of this masterpiece. From this stage, I usually try to take the painting further into my own direction, to clarify the insights gained to myself, to make them my own.

If you have any questions, want to share your experiences, or your own study of the same painting, please post a comment below!

If you want to receive notifications for further studies, please subscribe here.

If you want to follow the progress of the future studies, please add my Google+ page to your circles or like my Facebook page.