The individual who senses his aloneness, and only he, is like a thing subject to the deep laws, the cosmic laws. — Rainer Maria Rilke.

Last week, I wrote about Pavel Filonov’s insight into the rigid limitations of human mind, the simplistic maps through which we see the world. It’s not easy to see these maps within, because they are an intrinsic part of our thinking (and seeing) process, the seat of our identities.

But what happens when we drop these identities, at least momentarily, along with their rigid structures and patterns?

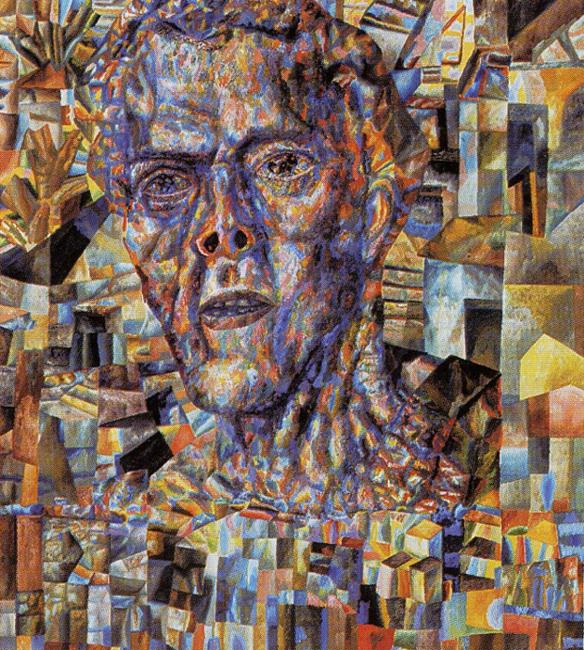

This, I believe, is the experience made visible here, in one of the later works from Filonov’s series of “heads”.

Sam Harris, in “Waking up”, quotes from a book by Douglas Harding, a British architect, “On having no head”. Harding describes the experience of a gap in the thinking process, which feels as though your head disappears from the subjective experience (along with your “self”):

It took me no time at all to notice that this nothing, this hole where a head should have been, was no ordinary vacancy, no mere nothing. On the contrary, it was very much occupied. It was a vast emptiness vastly filled, a nothing that found room for everything: room for grass, trees, shadowy distant hills, and far above them snow-peaks like a row of angular clouds riding the blue sky. I had lost a head and gained a world. . . . Here it was, this superb scene, brightly shining in the clear air, alone and unsupported, mysteriously suspended in the void, and (and this was the real miracle, the wonder and delight) utterly free of “me,” unstained by any observer. Its total presence was my total absence, body and soul.

Sam Harris goes on to describe how this experience is commonly discarded as a childish fear of death by people who haven’t experienced it (or rather — haven’t had a chance to notice the experience, because it is always there, all the time — just a bit out of synch with our conscious awareness). He likens it to the shift in perspective in front of a window, when its darkish outside: you can either see the world beyond the window, or you can see your own reflection. For a person focused on the world outside, the idea of seeing their own reflection there would seem surrealistic and absurd, but you can bring their attention to the reflection by pointing to the surface of the window with your finger.

The shift is harder to achieve with the actual experience of headless non-duality (although there are some variants of “pointing out” instructions in Harris’ book, too). But it is usually either one or the other: either you see the world outside (while “you” are here within your head), or there is no head, and the world is there in place of it.

In this painting, Filonov merges the two experiences into a single visual image of semi-present, semi-absent transparent head filled with the world — a kind of in-between state, or the very moment of shift between the two. Or could it be the state of an artist in the process of work: being both within an experience, and outside of it?

It is interesting to observe how the world changes as it enters this transparent head, how its straight lines dissolve and transform into something warmer, more organic. If you immerse yourself into watching the transformations, you might even catch a glimpse of this very experience, as the mental chatter ceases and is being replaced with shapes and colours.