Imagine you are sitting at a dinner table with a stranger, and, out of the blue, something unimaginable happens: this stranger seems to be someone who you love, but know to be dead and buried.

What would you feel?

This invisible inner turmoil is what Rembrandt has painted here, in “The supper at Emmaus”. The story comes from the Gospels: after the resurrection, Jesus “reveals himself” to two disciples, unexpectedly and “in a different form”. This “different form” probably means that the moment of recognition wasn’t supposed to be easy and straightforward.

In Rembrandt’s lifetime, the highest and grandest artistic aspiration was in religious paintings. This was the true art of the time. Portraiture was considered a lowly way to “make a living”. So when Rembrandt married Saskia van Uylenburgh, which gave him a modicum of financial freedom, he turned from commissioned portraits to religious paintings.

He was brilliant at anything to do with painting, including “conventional” religious paintings: huge, complex, multi-figure, story-telling compositions. A painter’s task was to visualise and show a pivotal scene, so that a viewer could “witness” it.

Painted in this tradition, the supper at Emmaus would include a self-evidently real Jesus emanating Divine Light. He would be the central figure of the composition, the main protagonist of the story. That’s what Titian (and many others) did with the same motive. In fact, Rembrandt tried this approach, too, in another painting.

But the painting we are looking at today is quite different.

This composition is simple, with few details, almost sketch-like and monochrome. The only hint of any realistic details is in the facial expression of one of the disciples. It is a mixture of awe and fear, the temptation to believe and the simultaneous temptation to pull away, into the comfort of normal, “real” life.

It is this man, with this very human confusion on his face, whom Rembrandt puts into the centre of his composition. It is his moment of recognition — or, to be more precise, not-quite-recognition-yet — that’s is the core motive of this painting. The figure of Christ is shadowed, not clearly visible — he may as well be a shadow you take for the ghost of a lost friend in a moment of wishful thinking.

There is this bright, supernaturally bright, light, but Jesus is not its source. This goes against the tradition, and it is especially striking in a painting by Rembrandt, because he is a master of presenting his human subjects as the source of light in the painting. And the other disciple — the one already on his knees at the bottom of the painting — is covered by an even darker shadow. He is not the one Rembrandt is interested in. And it was important for him, I believe, that the man in the centre faces his moment of recognition alone.

What this painting depicts is not a scene observed by a by-stander. It is the disciple’s inner experience.

This is the beginning of the evolution of painting from depicting things and people as they look like to how they are. What we see is not what happens in the visible world, but the inner experience of a man torn between his mundane and comfortable life and an unexpected vision of something extraordinary, other-worldly. There is a choice: to believe in the vision or to disregard as an accidental interplay of light and shadows.

This kind of experience is by no means limited to this particular story, this particular mythology, or in fact any religion at all. It’s about choices we all make, whatever our beliefs, every single day of our lives.

The painting itself looks as though torn between two epochs, between the past and the future. On the one side, there is realistic depiction of the scene, with some hints of symbolism. We see the man’s facial expression, a woman bending in the background on the left (perhaps to tend to a cradle), a ladder near the bottom, connecting two halves of the painting.

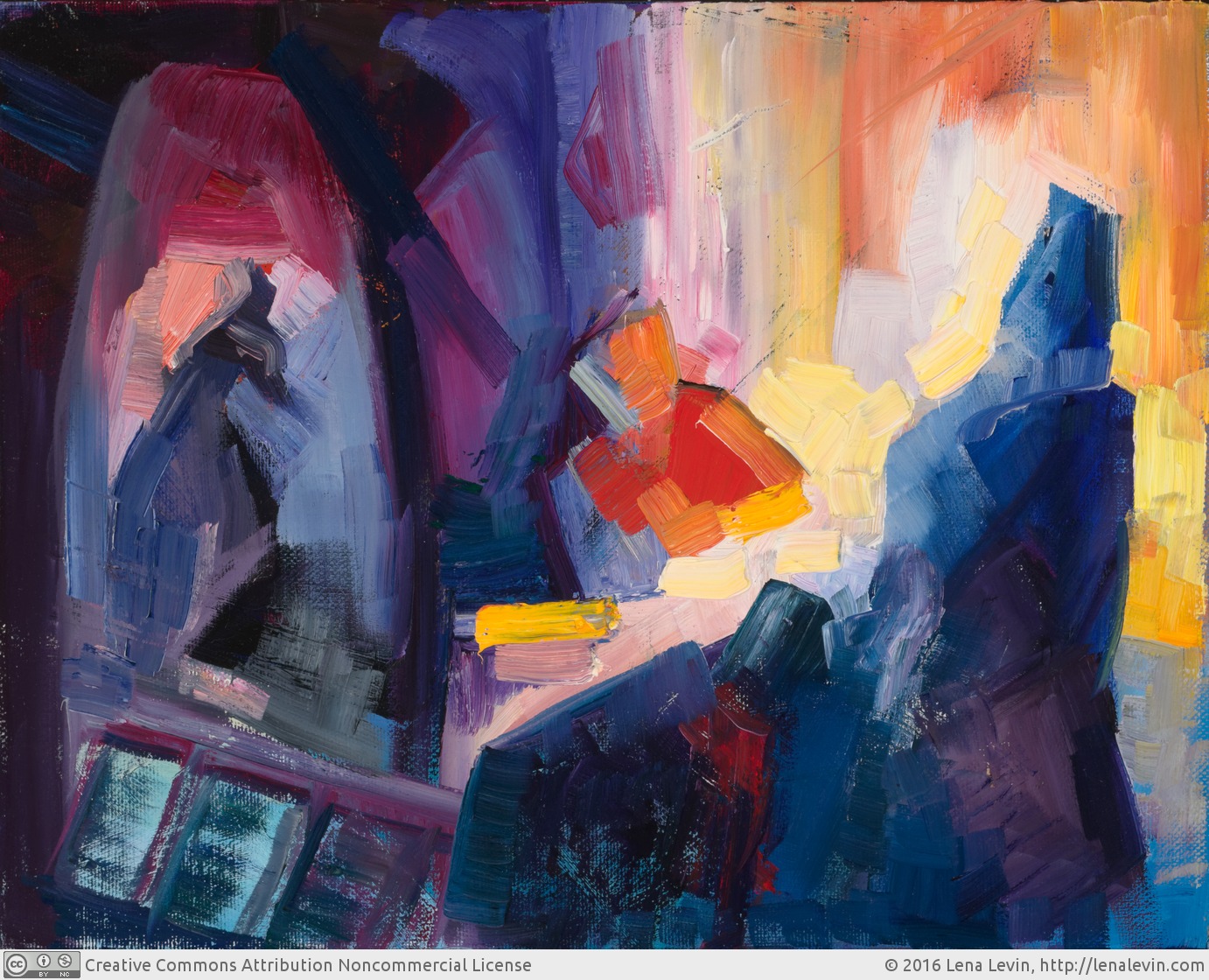

But the source of the painting’s power is almost purely abstract, non-representational. To understand how this painting works, to really see it “from the inside”, I did a quick painting study this week. The sketch focuses on these “abstract” pictorial aspects, and almost completely disregards the painting’s representational qualities.

So here are, I believe, two aspects of the composition to pay attention to when you look at this painting.

The tonal structure — the distribution of light and dark areas — is very simple and very unconventional. There is this stark, disturbing vertical division almost in the middle. It splits the picture plane, as though it were life itself: two sides of life, two aspects of human condition, crawling between heaven and earth. The protagonist is situated right on this split; to put it the other way round, the split goes right through him.

And there is a very strong contrast between immobility and dynamics. Most of the painting is very static, with the only exception of the man in the centre. It creates a dream-like stability of the whole space, as though the time has frozen into eternity, and only you can still move.