… had Rembrandt’s life conformed to the ideal scenario, this painting, “The return of the prodigal son”, would never have come to exist: one cannot paint what one hasn’t lived.

This is the second part of an essay about “The Return of the Prodigal Son” by Rembrandt. Here are the first one and the last one.

But What about money?

In a (despicable) bout of procrastination about writing this essay, I checked my Facebook stream. And there was a “sponsored post” right at the top: an offer to teach me how to make more money from painting.

This kind of stuff is really hard to avoid if you have any presence on the internet as an artist. One cannot blame Facebook’s algorithms for targeting me with this post. Statistically speaking, painters do struggle to make more money from painting, so a painter is likely to find this offer useful.

For me, though, it served a better purpose: it just happened to synchronise so well with what I was planning to write about that it immediately jolted me out of Facebook and into writing about Rembrandt’s “The Return of the Prodigal Son” (No, it’s not about how to make more money).

As you remember, the original story is told in very materialistic terms: the prodigal son returns because he has no money, and he plans to ask his father for work. The father rewards him with new robes, a ring, a fattened calf, and a rightful place in his rich household.

In Rembrandt’s painting, however, nearly all references to wealth are absent. Overall, it is a very austere, almost ascetic, painting. Even the father’s red cloak — the brightest and most intense area of the painting — doesn’t “boast” of being expensive. Instead, it is painted almost as a Matisse-like flat colour area. Here, Rembrandt doesn’t allow himself the sheer pleasure painting the richness of its fabric and the beauty of its folds. This deliberate restraint becomes all the more striking if you compare the way this cloak is painted with the treatment of fabric in his earlier portrait of himself as a prodigal son (click the image to zoom in).

In the first part of this essay, I suggested that Rembrandt strips the parable of its materialistic “clothing” so as to paint its essence, its intended meaning. But there is a bit more to it, because one cannot help feeling that this materialistic quality is an essential part of the story. The son’s ultimate reward might be not his father’s wealth, but it is his extreme poverty (rather than any kind of spiritual longing) that brought him home. Money is an essential part of the story, and Rembrandt knows this.

What went wrong?

Rembrandt started his work life as an extraordinarily successful painter. He also married a very rich woman (whom he loved deeply), a cousin of his art dealer. And yet he died in extreme poverty, and was buried as a pauper, in a church-owned numbered grave. There is no Rembrandt’s grave nowadays, because his remains were discarded twenty years later, as was the custom in the Netherlands at the time.

How did this happen?

There are three answers to this question, three different stories.

The first is the story of an artist who chose his inner calling over financial success. At the beginning of Rembrandt’s life as an artist, his style was well aligned with the spirit of the age. And since he was so unbelievably good at what he did, he naturally became a very fashionable painter. But his work and his patrons’ tastes evolved in different directions. In his old age, the patrons just did not like his paintings anymore, because he was ahead of his time.

The second is the story of a man who couldn’t handle money responsibly. With his initial success, and his wife’s money, he could have easily stayed independently wealthy and never bother about his patrons’ tastes — if only he had not squandered his money on an expensive house and a collection of art and rarities.

And there is a third one, the story of a man whose private life (after his wife’s death) did not conform to the puritanic mores of the time. He had two affairs with household servants, one of which resulted in a lawsuit (he had promised to marry, but didn’t) and another, in an illegitimate daughter. This led to social rejection, even ostracism. His patrons shunned him, and his art collection was sold for a pittance as a result of a conspiracy of bidders at the auction (even though it was really worth a fortune and could have well been considered a shrewd investment, rather than squandering his money).

All in all, one can choose to blame Rembrandt’s poverty on the contemporary society who failed to appreciate his genius, or on his own failings as a man. But what is shared by all three stories is the implicit assumption that something went wrong — that there was a “right”, better version of Rembrandt’s life (in which he doesn’t die as a pauper).

What lurks behind this assumption is this “ideal” of an artist’s life, in which they do their best work, get paid what it’s worth, handle their affairs responsibly and professionally, according to the mores of the time, and are rewarded with reasonable financial stability (as any good professional should be). If that doesn’t happen, we are tempted to find something (or someone) to blame.

Wouldn’t it be just so exceedingly nice if the society were (finally!) reorganised properly, and all artists were good, professional, and responsible — model citizens and professionals, head to toe, an art dealer’s dream come true?

There is just one tiny little hiccup in the midst of all these niceties: had Rembrandt’s life conformed to this “ideal” scenario, this painting, “The return of the prodigal son”, would never have come to exist: one cannot paint what one hasn’t lived.

Rembrandt’s choice

What would you have chosen: to have painted such a painting or to have lived a financially secure life and get a respectable burial after death? What is the “right” version of Rembrandt’s life — the one in which he is upright and wealthy, or the one in which he paints this painting? The life of the elder son, or the life of the prodigal son?

Rembrandt’s own choice is clear. Whichever story we prefer, he chose his path himself. He was not a victim of circumstances and “society”, but the maker of his own life.

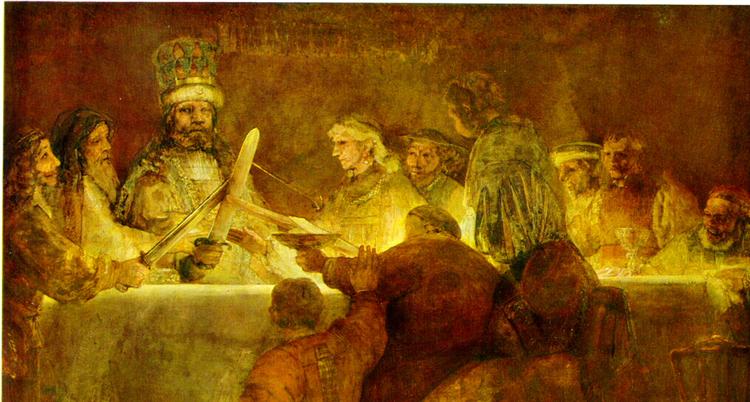

In all honesty, can you blame a patron for rejecting “The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis” after they commissioned a painting from the author of “The Nightwatch”?

It is almost as though you commissioned a painting from Rafael and received one by Picasso instead — that’s just not what you asked for, and absolutely not what you expected. Could Rembrandt have painted something to meet the expectations of Amsterdam city council (who commissioned “The conspiracy of Claudius Civilis” for their city hall)? Something more in the style of “The Nightwatch”, more fitting for a romanticised notion of this rebellion they had in mind? Something that would have been accepted and paid for? Technically, I am sure he could do anything — but this just wasn’t something he was interested in doing. It was his choice (just as it was his choice not to hoard his wealth and to defy puritanical conventions).

This choice is what opened the space for “The Return of the Prodigal Son” to emerge, and the beauty of this choice is present in the painting.

If there is any indication of wealth here, it can be found in partly covered articles of the father’s clothing, those he wears under the red cloak. His sleeves in particular are glistening with silvery colour (the link will take you to a zoomed-in version of Google Art Project reproduction).

But the father’s arms lead our eyes to the son, and to his rags. And it is here, in the son’s tattered robe, its folds and its holes, that Rembrandt finally relinquishes the overall austerity of the painting and lets out all his power as a painter of sheer material beauty of the world. As far as this beauty is concerned, the son’s rags is the richest and the subtlest area of the painting. If the father’s sleeves are silver, then this is pure gold.

Just zoom in and let your eyes follow all these folds for the sake of their usually unacknowledged beauty, enjoy the interplay of their warm, golden, earthly colours (better still, study this area by doing — by trying to replicate its colours with your own hand).

If there was, for Rembrandt, a way of saying that he knew and appreciated the beauty and significance of his poverty, this is it. He would not have swapped it for a comfortable bourgeois life — he is the prodigal son, not the elder son.

I suspect that being an artist and choosing the part of the elder son just don’t go well together.