As we are diving deeper into the process of painting study, you might have already encountered some of its ups and downs, joys and tribulations. In part, they are the same as the usual ups and downs of painting process, but not quite — because it is not just painting, and not just learning to paint; it is also (and probably first and foremost) the process of forging a deep connection with a masterpiece of art as its viewer.

I will return to the “technical” side of this process next week, but today’s post is all be about its emotional core. By the way, these are not always easy to differentiate, because painting (and art in general) is a somewhat mysterious process where the technical and the emotional, the material and the spiritual, are fused together, intrinsically inseparable. Or, to put it the other way round, art can temporarily free us from these dualities, however pervasive they are in many other realms of life.

You will probably discover that the process you are going through enriches your life in new ways and makes you more present to the incredible beauty of the world, but the painting you are connecting with may also stir painful feelings, and open emotional “Pandora boxes” suppressed and “hidden” long ago. That’s what paintings are supposed to do: they touch and heal the human soul. And in the process of painting study, we are connecting with them at a deeper level — and let them touch and transform the soul more powerfully — than just in the process of viewing.

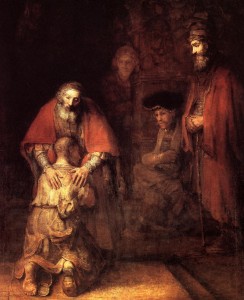

Since the process is so prolonged, so distributed in time, one might encounter these long-suppressed painful feelings without even realising that it’s the painting that has unlocked this particular Pandora box. Even though I’ve done painting studies many times, this what happened to me over this last couple of weeks: it took me sometime to realise that it’s “The return of the prodigal son” that unblocked this wave after wave of emotional turbulence, linked to events long pas and filled with resentment, and sadness, and guilt, and longing for parental love.

So if you experience something like this, too (and this can even be felt as a physical pain in your body — because all these things are connected), just remember that it may be the process of painting study that has unblocked suppressed emotions. If this happens, take it as a sign that the deep connection with the painting is really beginning to emerge, that the painting is doing the work it was created to do.

One can feel differently about one’s own feelings, especially when they are painful. Sometimes we cherish them, and hold on to them — because, after all, they define and shape who we are as human beings. And sometimes we would rather to let them go. But suppressing them doesn’t help in either case (and, from what I hear, it can even be bad for one’s health). So if a painting releases suppressed feelings, it can be a healing experience.

You probably have your own ways of “dealing” with painful feelings, but I will share mine just in case it might prove helpful. To the best of my abilities, I stay with these feelings, witness them and really feel them. An essential part of it is not to get caught up in all the stories my story-telling minds tend to spin around them: I’ve come to realise that they are just the mind’s way to run away from uncomfortable feelings; they prevent us from both feeling the emotions and from letting them go (these processes might not be so different after all). These stories do come up, inevitably, because it’s rather difficult to make one’s mind shut up, but we can try and “witness” them rather than identify with them: they may or may not be “true”.

And, most importantly, painting! One of the greatest gifts of painting is this release from identification with our own “stories”. Paintings help us witness and feel painful emotions, and let them go — protected, to an extent, by the sacred space created by art.

To be honest, this time — caught up in this emotional turbulence and other work — I’ve made the mistake of not starting my final study when the impulse was already there, and “paid” for that delay with some really emotionally hard time. If at all possible, don’t repeat this mistake — pour your feelings into your work, paint through them. The feelings stirred by the masterpiece, however unrelated they may seem, will help you approach this painting study from the same place of “inner need” where the original painting emerged.

This post is a part of online program, “The Making of a Painting Masterpiece”.