If you are ready to approach your blank canvas, let’s talk about various approaches to starting a painting.

[Even if you aren’t going to begin your final study right away, it will be useful to keep these alternatives in mind for some time to make the best choice when the time comes (because a good start is often what makes or breaks the painting).]

The very first choice one has to make when starting a painting is whether to begin with a white ground, or with a colored ground — that is, with a layer of strongly diluted paint (most often, a muted warm colour — but, depending on the circumstances, it can be also a grayish blue, just a light grey, or a more intense color layer).

There are two general advantages of colored ground. First, it will make it easier for you to “judge” all the further colours you will be adding to the painting — that is, to decide whether they are “right”, especially with regards to their tonal value (this is because the bright white of the canvas blinds and confuses the eye to some extent). Secondly, it will give a unifying harmony to your final painting, and it might also “save you” from the white of your canvas showing through your paint. But this latter advantage can also be a drawback, because the choice of the ground colour is there to stay, and it can limit your further options: in one or another way, it will influence all your color areas.

In the process of painting study, there is, of course, an additional consideration: how did the original begin? Is there a unifying underlying layer “showing through” the painting? If yes, it will help you to start with a similar layer. On the other hand, as you will see from what follows, some strategies of starting a painting are excluded by choosing to use a colored ground.

The second choice is between three major strategies:

- Color block-in. In this approach, you start with covering the major colour ares with a very thin layer of appropriate colour (the whole canvas is covered, so you first layer may look similar to your simplified colour sketch). The boundaries between these colour layers can be preliminarily sketched in with soft vine charcoal. However, since it’s a very thin layer of paint, you will be able to correct and refine these boundaries later on, at least if you are working with opaque colors (oils or acrylics). Most of this layer will be covered by other colors later in the process, and become invisible when you refine shapes and colors. Its purpose is to give you the first, simplified (but, approximately, “right”) vision of the future painting right away. This will make all further steps easier, because you will have an approximately correct “context” for each area of the painting. It is, in a sense, the easiest way to start — because you can change everything later on, you aren’t striving for perfection here. This layer can be painted over a coloured ground, or directly on your canvas. In the next steps, you will be gradually introducing distinctions between smaller colour areas (and your paint can gradually get thicker and thicker).

- Monochrome underpainting. In this approach, your starting point is tonal values and “drawing” — colors will be introduced only later on. The advantage of this approach is that you aren’t required to “judge” tonal values and hues at the same time, and you can get your drawing and composition right before you introduce colour. This is especially helpful if the drawing is going to be complex and/or very realistic. In the traditional approach, an opaque white (Titanium White, or Underpainting White) is used for monochrome underpainting, so some thickness of paint is introduced right away (and, once dry, it is there to stay). In this case, colored ground is very helpful — you can use it as your mid-tone, focusing your attention on darkest and lightest areas and their shapes. A more modern approach is to use the white of the canvas as the white of your monochrome underpainting, using very thin paint throughout (and wiping it away with paper towel if you need to “erase” something). This approach allows for more flexibility in the further process (since you don’t introduce thick paint from the very beginning, and you can wipe away “mistakes” more easily), but, of course, you cannot use it in conjunction with colored ground — you need the white of the canvas.

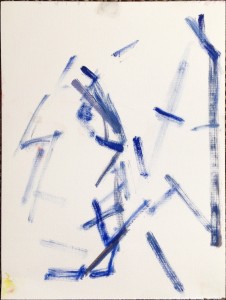

Cézanne’s approach is to start with the geometric structure of the painting, using diluted and greyed down French Ultramarine to indicate the location of darker contours of major planes. Having established this structure, the next step is to build up colour modulations, in small patches of colour, going from darker to lighter (and warmer) areas. In this approach, one doesn’t cover large areas with a unifying layer of paint; the colour is built up patch by patch, one small “plane” at a time — but working with the whole canvas all the time. This approach is incompatible colored ground either. All in all, it requires more experience and confidence with color than the other two.

Cézanne’s approach is to start with the geometric structure of the painting, using diluted and greyed down French Ultramarine to indicate the location of darker contours of major planes. Having established this structure, the next step is to build up colour modulations, in small patches of colour, going from darker to lighter (and warmer) areas. In this approach, one doesn’t cover large areas with a unifying layer of paint; the colour is built up patch by patch, one small “plane” at a time — but working with the whole canvas all the time. This approach is incompatible colored ground either. All in all, it requires more experience and confidence with color than the other two.

In many (though not in all!) paintings, there is a clear distinction between a focal (usually more detailed) area and the rest, the overall background “context” supporting the focal area. If so, the next choice is whether to start with detailed work on the focal area, or with establishing the overall structure of the painting — one still has to work on the whole canvas to keep it unified and harmonious, so it’s rather a matter of focus of attention than an all-or-nothing choice.

Please think about these options — and which path you would want to take with your chosen masterpiece — before you start your final study. And remember: if you need my advice, you know how to contact me!

This post is a part of online program, “The Making of a Painting Masterpiece”.