From “Why painting?” series

From the very beginning of this “Why painting” series, I decided to think about paintings-as-things and painting-as-process separately: however artificial this separation may be, this was necessary for me to be able to face the question of whether paintings are needed in the modern world in a detached enough manner. So the first part of the series was all about paintings-as-things; now, it’s time to turn to painting-as-process.

As it turned out, I do believe people need paintings-as-things — both paintings in museums, and paintings in their living spaces. But this belief, in itself, cannot do away with the very real, and very disruptive, disconnect between painting and life. In material reality, this disconnect manifests itself as artists’ storage spaces filled with paintings unclaimed by people whose life they could have enriched.

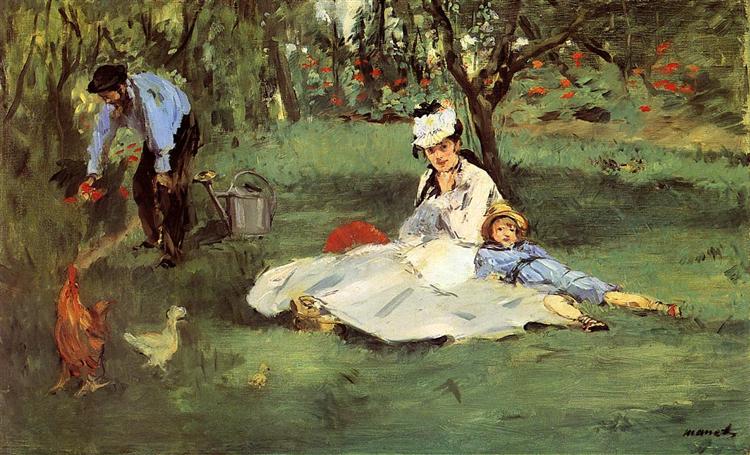

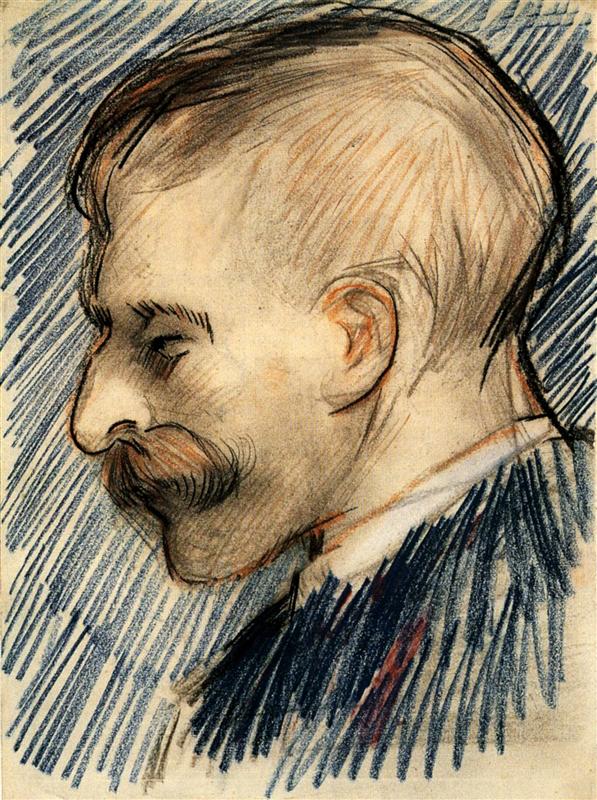

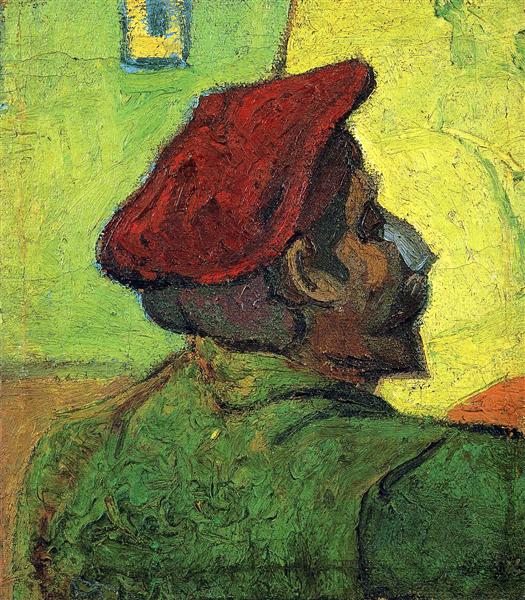

These heaps of “stored”, unclaimed paintings is the everyday reality for the vast majority of painters — even if the good ones, and even the relatively successful ones (unless, of course, they destroy their own paintings on a regular basis, as some of us do). It is certainly the reality for any beginner, and this has been a life-long reality for some of the greatest painters this world has known (suffice it to mention that Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam only exists because his brother’s family saved his unclaimed paintings for the posterity).

For a living painter, these heaps of unclaimed paintings tend to cast the shadow of meaninglessness on the whole process: why paint if the result doesn’t get to participate in life? Why go out of your way to say something if nobody listens?

Our whole culture, our languages, our patterns of thinking are very result-oriented. Our brains are not really trained to value processes for their own sake, at least not when the process naturally leads to such a tangible result as a painting — an apparent locus of meaning for the whole activity (it is not that bad with other processes — playing a musical instrument, dancing, surfing, walking — but the creation of “things” seems goal-oriented by its very nature). If nobody needs or wants the result, the process seems to become worthless, a pointless waste of time and resources.

And, even more pragmatically, what the hell is one supposed to do with all this stuff once the painting process is over? This is a very real question. I have recently talked to someone who just stopped painting because they have no space for more of them. And for me personally, even the anticipation of these heaps of paintings to deal with had been a very real block against returning to painting (I happen to hate having too much stuff on my hands; and living between countries, with no permanent place of our own, exacerbated the problem).

All in all, the need for painting-as-process has to be looked at in the context of this everyday reality of unclaimed results. Is there a value in the process of painting if we assume, for the sake of argument, that it has no tangible “result” at all, except for heaps of paintings you don’t even have a place to store? It’s not just that this process doesn’t earn you a living, but nobody wants your paintings (except maybe a couple of compassionate friends and family members), and you are by no means certain that they are good enough to save for posterity (as a matter of fact, it’s most likely that they are not, at least not in the beginning). It drains all kinds of resources, it creates storage problems, it brings no fame and no money — do we still need it, and want it, if that is the case?

As I was writing this, it crossed my mind that there is another process with the same exact set of drawbacks, including the resulting storage problems: shopping. Still, many people seem to find this process so emotionally rewarding that it can become addictive… Seems like a demeaning company for painting, but it’s still nice to know that these drawbacks don’t necessarily discourage people from doing something.

There is this quote attributed to Howard Thurman, which seems to make the answer simple and straightforward:

Don’t ask what the world needs. Ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is people who have come alive.

However strongly I agree with this thought, it might not be that simple, because it’s not that simple to understand what makes you “come alive”. As a matter of fact, it’s not even that easy to understand what it means to “come alive”: are we not, after all, alive just by virtue of not being dead yet? One needs to experience a tangible, unmistakeable gradient in vitality to get even a hint of what this expression points to. And the problem is, it may take a long period of doing before this change happens — especially if the doing involves a long learning process. So it isn’t a matter of just asking: you’ve got to start doing before you can get the answer.

Let me tell you my own story. I used to paint (and studied painting in formal settings) all through my childhood and youth, but when when time came to choose what to study in university, I decided for a slightly more conventional “career”, and became a linguist (for a variety of reasons, most of which lost their relevance a long time ago). At the time, I believed I would be painting anyway, but daily life has its ways of interfering with such intentions. Historical calamities, personal tragedies, family, interesting and rewarding work, emigration — all in all, painting disappeared from my life (if not from my thoughts) for many, many years. And if I felt less alive than in my greener years, I assumed it was only natural, that this is what is supposed to be happening as you grow older.

And then, somewhere midway on my life’s journey, I found myself in Dante’s dark forest (for, exactly like he describes, the straightforward pathway had been lost). I had just made a couple of drastic self-sabotaging moves in my linguistic career (even though I didn’t fully realise the extent of this self-sabotage at the time), and I followed my family to a completely new and alien land (to this country, California). I sometimes recall the darkest night of my life, the dark night of the soul — so dark, so desperately hopeless that I tried, but couldn’t retrieve a single happy memory to help me out of the darkness. It’s a strange feeling — like being unable to recall the word you need: I knew these happy memories were there, somewhere, that I used to have some “resource states” that could have pulled me out of this darkness, but the darkness was so dark that I couldn’t find them.

Perhaps the (by now) more conventional way out at that point would be to ask for antidepressants — and indeed, there were some people who advised me to do just that. But I had always mistrusted chemical solutions to spiritual problems, and I still had this nearly forgotten childhood dream of painting — so I bought some paints and drawing supplies instead.

I wish I could tell you a story of an instantaneous revelation, a dramatic turn in my life uphill and towards the light — but I cannot. It was a much longer, and much more convoluted story, certainly beyond the scope of a single blog post: painting would pull me out of depression, and — temporarily healed — I would return to life-as-usual, to what seemed like its pressing demands. And this circle repeated itself several times before I finally “got the message”. And even after that, there was a long and windy road to really “coming alive”.

There are two reasons for telling you this story. First, painting is one of the process that can make one come alive — and the world needs that, perhaps more than ever. There is more to this than finding one’s path, the meaning of one’s life: there are some intrinsic properties of the process which change your way of being, of seeing, of interacting with the world, even if it’s not your “vocation” (but more like a vacation from “real life”), and even if nobody ever claims the results. I will return to this topic in the next (and last) installment of this series.

Secondly, whatever one’s path to coming alive really is, be it painting or something else, the inner voice that keeps telling where it is can be barely audible in the noise and business of modern life, and the rewards to listening to it may not be immediate. Arguably, this noise, this overwhelming meaninglessness of business, which keeps shutting down our inner voices, is one of the causes of the “epidemics” of depression, and other mind-body disorders — the modern plague of the “first world”. What the world needs, then, is more people who make an effort to shut down the noise, and listen to the inner voice.