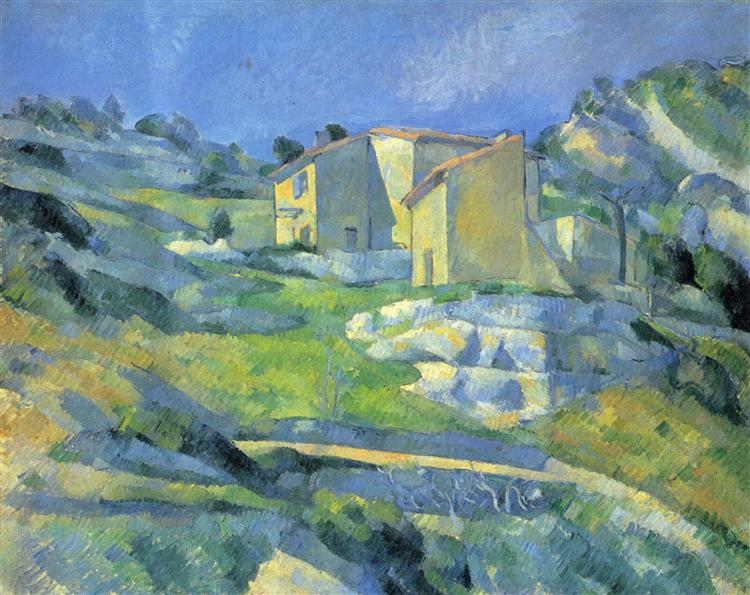

Gottfried Richter, in “Art and Human Consciousness”, discusses this quote from Paul Cézanne:

… The landscape mirrors itself, thinks itself within me… Perhaps this is all nonsense, but it seems to me as though I myself were the subjective consciousness of this landscape… (p. 234)

There is this weird paradox of human condition — the experiences most worth sharing are barely shareable. These are experiences that lie beyond the realm of “common sense” — the social agreement on what reality is and how it works — and thus seem like non-sense once put into words. But sometimes a miracle of connection happens — when there is a certain readiness in the listener’s mind: a hint of experience vaguely felt, but unexamined, unnamed. Then, a spark of recognition is possible, and it can be transformative.

That’s what happened to me when I read those words — I seem to know what he means, however “off” it feels from the common-sense point of view. And now I have a seemingly impossible task before me: to unravel the essence of this experience, so the words don’t sound like non-sense anymore. Because this is the promise of painting, the ultimate answer to the “Why painting” question I have been trying to address in this series of essays.

I have recently taken a course entitled “What is a mind?” on FutureLearn.com, taught by Professor Mark Solms of University of Cape Town. It is a long and fascinating course, but the final answer to the title’s question was, in short, this:

Mind is the subjective experience of being a body.

This is an answer given by a neuropsychologist (not a philosopher, not an artist), and “body” appears here as a kind of separate, isolated entity. But our bodies are very much an inherent part of the environment we find ourselves in, interconnected with it in an infinite multitude of ways — from physics to chemistry to biology to psychology — most of which are well beyond the scope of our conscious awareness, beyond the subjective grasp of the mind. We know — to some extent — about these connections, but they are mostly not a part of the direct subjective experience of life.

What Cézanne’s words name is the ability of painting-as-process to bring these connections closer to the painter’s conscious awareness, to “unhide” the intrinsic unity of life and make it visible to “the mind’s eye” — so that the mind becomes the subjective experience of something larger than an individual human body. Viewed from this perspective, the experience of being the subjective consciousness of a landscape you are painting (instead of the subjective consciousness of a seemingly isolated body) begin to seem as something much closer to “objective” reality than the everyday, “common-sense” consciousness of an isolated “I” within an isolated body. Because the unity between the body and the landscape is objectively there — the question is only whether we perceive it subjectively.

Painting, from this vantage point, emerges as a possible way to overcome the modern mind’s “world-alienation”, to alleviate the everyday suffering of our little Cartesian thinking “I”s, sitting within our bodies and struggling for a modicum of control and freedom in an alien, insecure, dangerous world “out there”.

Does everyone need this? Probably not, but some of us certainly do.

Is painting the right path for everyone? Probably not either. I recently had a conversation with Suze Kenington from New Zealand, who coaches horse-riders. In spite of what seemed like an infinite gap between what we try to teach, a striking commonality emerged in this conversation, which she put into words. After all, she said, the point is to feel the unity of life, and which path one takes — painting or horse riding — doesn’t matter so much.

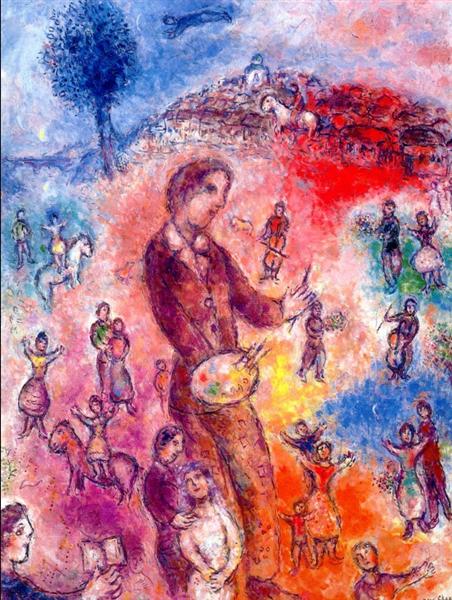

Still, painting, as a process, combines three qualities which make it — it seems to me — almost uniquely suitable for overcoming the modern mind’s world alienation and feeling our way back to the unity of life.

First, it expands and enriches the sense of vision — and, as Richard Dawkins said somewhere, we are throughly visual animals (I don’t put it in quotation marks, because I am not certain it’s an exact quote, but it’s a quote). For the vast majority of us, vision is the core sense (as witnessed, among other things, by the fact that words for seeing is the major source for words of perception and cognition in world’s languages). Sharpened and expanded within the painting process, it strengthens our connection with the visual reality — and thus with life itself.

Secondly, it is a very physical, very bodily activity; or rather, it’s an activity that, by its very nature, defies the mind-body duality — otherwise so pervasive in our lives and in our thinking patterns. It is becoming increasingly clear to science that our cognition is embodied, that even most abstract thinking relies on body’s “knowledge” — but in painting, it is intrinsically impossible to disregard this connection, which unites eye, mind, heart, and hand.

And, last but not least, it is, to a large extent, language-independent. It frees us from “stories”, including self-stories, which define and isolate us in everyday life. In other words, the painting process forces the painter to be present, to pay attention to what is — to drop all stories, rationalisations, and self-talk. In a sense, it’s a kind of meditation — but with your eyes open and your body active; a meditation which dissolves the duality between the inner and the outer.

The value of all of this is completely independent of the “result” — the success of the final painting(s), however one wants to define “success”, be it realistic representation of something, expressive use of colour, money, fame, self-expression, or contribution to the evolution of human consciousness (in no particular order). Or, to be more precise, the most important — or even the only really important — “result” is the change in the inner state of the painter, which can be meaningful and transformative at any level of mastery and talent.

I began this series with the idea that the real question is whether painting still has a role to play in the evolution of human consciousness, and I believe this last essay of the series is my answer: there can hardly be anything more important at the present stage of this evolution than overcoming world alienation and feeling our way towards the unity of life.