Are you an artist? Am I an artist?

What does it even mean, to be an artist?

This question has been bothering many artists (and some non-artists), especially over the last couple of centuries. Obviously, a lot has been written on this topic — by this time, perhaps more than one can read in a lifetime.

But the longer I read, the more I get dizzy with some version of “double vision”:

Zoom out, and there is this towering figure of an artist — a rare, prophet-like genius, born once in a while as a gift to humankind. Zoom in, and being an artist emerges as the birthright of every single one of us; all it takes is to claim it.

Is there a connection between the two images? Can we focus our vision in such a way that they merge together?

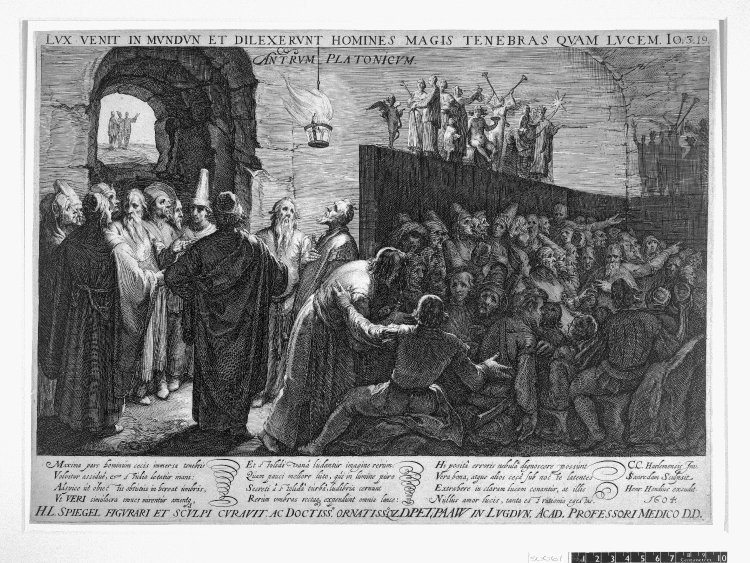

In Plato’s cave allegory, people are chained in a dark cave from childhood. There is a fire behind, but they cannot turn and see it — all they can see is shadows on the wall in front of them, and they take this show of shadows for reality. If one of them does happen to see the fire, they will first be blinded by the light. And if they get out of the cave — and it’s a steep, rugged accent — they will be blinded by the sunlight even more. But as their eyesight adjusts, they will gradually learn to see the upper, sunlit world, and recognise it for the real reality.

But what happens, Socrates asks in Plato’s dialogue, if this enlightened person returns to the cave to share the news with the fellow prisoners?

Of course, he (or she) will have a hard time seeing in the darkness again, so the others will conclude that the journey outside harms one’s eyesight. Their news from the upper world will be dismissed as madness, a delusion of blindness. Nobody will want to go out — the chains won’t even be needed to keep them glued to their shadow reality.

The cave allegory was intended to illustrate the fate of a philosopher. Artists differ from philosophers in the way they communicate their message: they have the power, the talent, the skill to make others see. They can make their fellow prisoners experience the world outside the cave of shadows, even those who aren’t really inclined to leave it. This is the story of a prophetic genius.

But this is the end of the journey, its result, its destination. It is not even the story of being an artist — it’s the view from the outside. The actual process of being an artist happens within the journey, it is in climbing this rugged accent out of the cave. To get out of the cave — this is every human being’s birthright. It’s just that the accent is steep, and the light blinding, and the “real life” in the cave of shadows, busy and familiar.

The cave allegory does help me with my double vision conundrum: it unifies two ideas of being an artist into a coherent image. But as any allegory, it only goes as far as it does; beyond that, it can be misleading (may be because I have just stretched it beyond its intended meaning — from philosophy to art).

So there are two caveats.

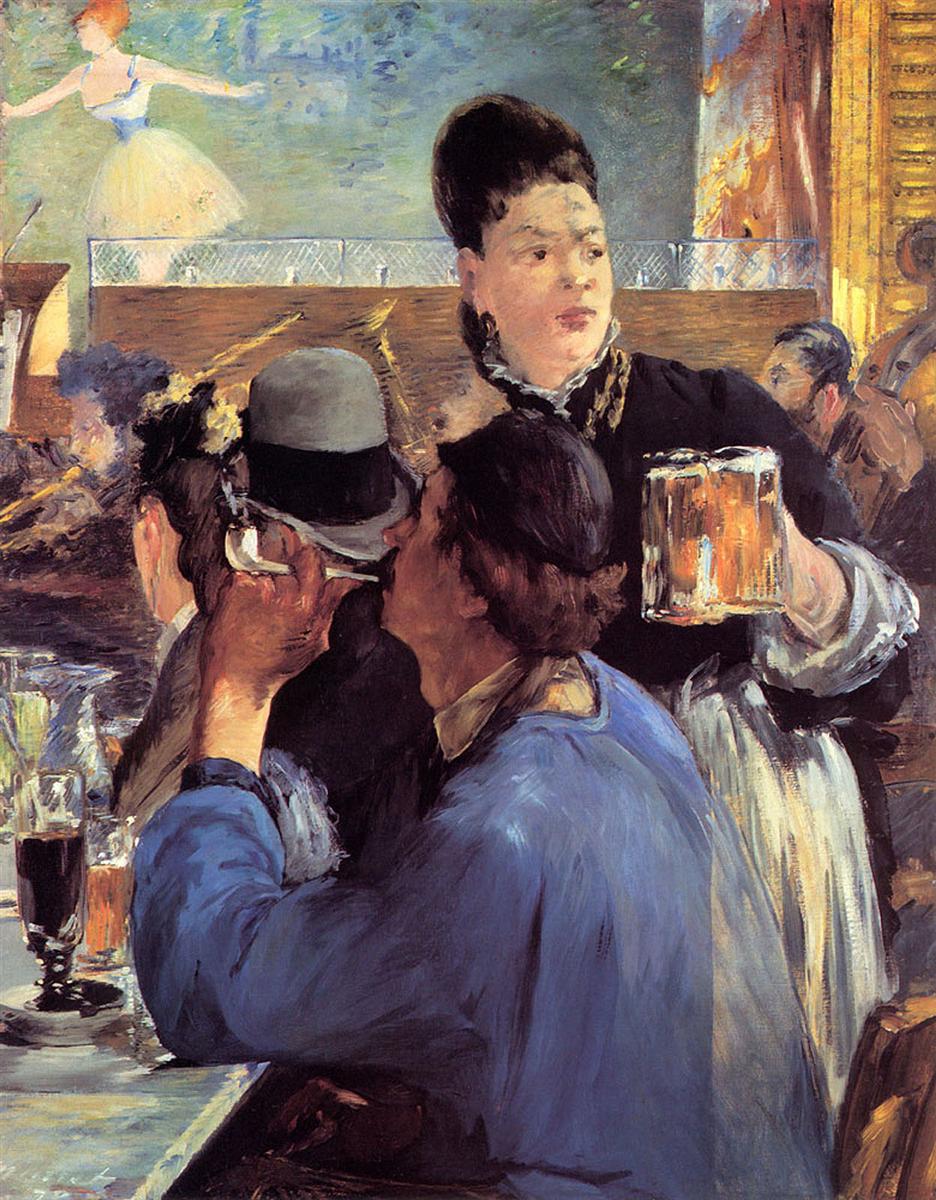

Between accepting the truth of the traveler’s report and rejecting it as pure madness, there is a third option: take their message as entertainment, as fairytale, as a way to enrich one’s life, make it more endurable — without jeopardising one’s view of reality. This hardly ever happens to philosophers (they aren’t entertaining enough, I guess), but this is the received way of “accommodating” art. It is rarely perceived as (in Beethoven words) “a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy”. A book can be fascinating, a painting, beautiful, a symphony, magical — but when the experience is over, the audience tend to return to their real life in the cave of shadows.

And this, by the way, presents a temptation anyone who wants to claim their birthright has to bear in mind: one can (rather easily) entertain without ever actually climbing out of the cave. Paint a pretty picture. Write a thrilling adventure. Compose a catchy tune. Few will notice that it’s not quite the same thing.

The second caveat is that the journey out of the cave does not just happen once in a life time: you are out, you see the upper world, you go back and tell your story, and that’s it. The truth is, this journey happens (or doesn’t) in every single moment — with every single poem, every single painting, every single sonata. And you always hope to climb a bit further, to get a bit closer to the sun. Beethoven again:

A friend once asked Anna Akhmatova, a great 20th Russian century poet, whether the writing of a poem turned into a different experience after she had become a recognised, famous poet. Her reply was: no, it is always the same: a naked human upon a bare soil.

So is this, then, everyone’s birthright: to be always climbing, naked, out of the cave and back — and hope to be taken as an entertainer (rather than a head case) upon your return?

This sounds about right to me. And after all, there is joy in the very effort of climbing which is hard (if not impossible) to find in the comfort of the cave (or in any other comfort, for that matter). People climb mountains not just to see the view, and certainly not just to tell a story afterwards.