This practice is intended to find explore major planes of the picture, which lie “behind” the picture plane. We are interested in painted planes, not the planes being depicted (for example, we can “reconstruct” that Chagall shows us the background of a circus (we see the little figures of audience members), but he did not paint any plane there. On the contrary, Mary Cassatt’s pictorial space contains (at least) two planes corresponding to a similar “object”. If this distinction isn’t quite clear, read on: it will become clearer!

The practice consists of drawing a small scheme of all the major planes of the masterpiece’s pictorial space in their relationships to one another. Start with sketching a picture box, representing the pictorial space. The goal is to locate all major “events” of the picture within this space, not (just) on a plane.

Here are the major ways the pictorial space is constructed:

- Size of similar objects: if two objects we know must be similar in size are depicted as different, we assume that the smaller one must be further away.

- Location “on the ground”: if the lower edge of one object is located higher on the picture plane than the lower edge of another, we assume that the former one is further away (insofar as we assume that they must both sit on a horizontal surface: if an object is flying in the air, this visual clue is lost).

-

Paul Cezanne. Pine and Rocks. 1897. Overlapping planes: if one plane partially covers another, the latter one must be further away. When we see overlapping planes, we tend to try and reconstruct the amount of space that between them. Pay attention to whether this space is actually there in the painting, not just in the reconstruction based on your knowledge of reality (for example, there is no distance — no space — between Cézanne’s trees and the background blue plane of the sky, which is — in this painting — completely parallel to the picture plane — quite unlike how we usually “think of” the sky).

-

Vincent Van Gogh. Wheat field with Crows. 1890. “Dynamic planes”: that is, planes in the pictorial space that are not parallel to the picture plane. When looking for (and at) dynamic planes, beware (again!) of the possible difference between your knowledge-based reconstruction, and what is actually there in the painting (for example, we know that fields are generally horizontal — so a painted field “ought to be” perpendicular to the picture plane; but that’s absolutely not what Van Gogh has painted in “Wheat field with crows”).

Of course, dynamic planes are themselves illusions — in “reality”, they are just two-dimensional shapes, which fully belong to the picture plane. This illusion is created in two major ways:

- Linear perspective (roughly, parallel lines becoming closer indicates distance; circular objects turning into ellipses if they belong to dynamic planes).

- Colour (this covers both changes in hue — things that are further away appear “bluer”, and changes in tonal values indicating how light falls on the plane).

We aren’t interested in details of these devices here; I mention them only to indicate that there are no other ways: if neither of these are present in the painting, then the plane is not painted as dynamic.

In this study, focus only on spatial illusions explicitly created by the painter using pictorial means, not on how you can reconstruct the space being depicted based on your general knowledge.

Start with locating “ground” plane(s), like the surface of the earth of a table. Are these planes painted as horizontal, or do they appear “slanted”, not perpendicular to the picture plane?

Start with locating “ground” plane(s), like the surface of the earth of a table. Are these planes painted as horizontal, or do they appear “slanted”, not perpendicular to the picture plane?

Locate “static planes”, that is, planes painted as parallel to the picture plane, starting with the background plane — the “back” of the picture box.

Once this basic structure is established, start sketching in other dynamic planes. Pay attention to their angles, in relationship to the picture plane and to one another: they needn’t be “realistic”.

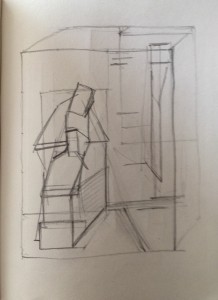

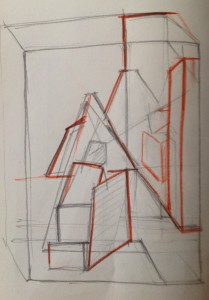

This is a challenging exercise; to illustrate this point, I am attaching my first couple of attempts to study the pictorial space of “The return of the prodigal son” (I’ll have to spend much more time on it!). But the more challenging this practice, the more useful it will be for your final study.

This is a challenging exercise; to illustrate this point, I am attaching my first couple of attempts to study the pictorial space of “The return of the prodigal son” (I’ll have to spend much more time on it!). But the more challenging this practice, the more useful it will be for your final study.

Once you have done a couple of such sketches, consider the next exercise.

This post is a part of online program, “The Making of a Painting Masterpiece”.