Look in thy glass, and tell the face thou viewest

Now is the time that face should form another;

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose uneared womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime:

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see

Despite of wrinkles this thy golden time.

But if thou live remember’d not to be

Die single, and thine image dies with thee.

Click here to watch and hear Simon Callow reading the sonnet.

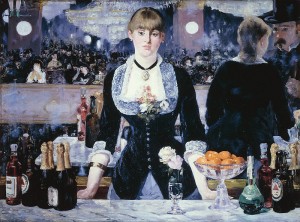

This painting is the most straightforwardly an “illustration” of the sonnet of all I’ve done so far, perhaps because it invokes a human image which directly appeals to my own sensibilities – the image of a mother who looks at her son as a mixture of a mirror and a time machine. The scene, as depicted, vaguely suggests identification between the viewer and the mother (reflected in the mirror from which the young man turned away). In this sense, the painting borrows its motive and its overall conceptual structure from Eduard Manet’s last unfinished painting, in which a large mirror behind the girl’s back reflects a man talking to her – be it the viewer or someone she thinks of.

I was briefly tempted to go with the current historical near-consensus with regard to the identity of the young man to whom Shakespeare’s sonnets might have been addressed – and integrate into the painting, in one way or another, the likeness of Henry Wriothesley, the third Earl of Southampton. Yet if this really is Shakespeare’s character and addressee, than he was probably right when he wrote, repeatedly, that his verbal depiction of the young man’s beauty is more impressive and capable of making it eternal than any paintings of contemporary artists. Be it as it may, this image doesn’t inspire my imagination, so I decided to borrow another character from roughly the same time.

“My” young man, therefore, comes from Titian’s “Man with a glove”. I did not wish for the character of my painting to be a “copy” of Titian’s in any sense, but rather to be recognizably the same man – one of the most iconic images of Renaissance young and beautiful nobleman in the history of art.

In combining two “sources” from so different chapters in art history – the late nineteenth century impressionism and the height of Italian Renaissance, this painting opened a new path in my work with the sonnets, in which great paintings of the past realigned and rearranged themselves before my sight, suggesting themselves as visual counterparts of Shakespeare’s poetry, creating perceptible impression of a great ocean of art in which waves don’t really care about differences between art forms.

Geometrically, the double portrait reverses the structure of two earlier landscapes, putting the golden section vertical (interpreted as the edge of the mirror) on the left, behind the young man, whereas the less prominent lower horizontal is suggested by his shoulders, dissolving into darkness at the bottom right. This creates the smaller square in the right top corner of the picture plane, which coincides with the mother’s portrait.

In terms of colour, the painting runs away with Shakespeare’s mention of “golden” time: it plays on the contrast between a range of yellows and ochres and (mostly French Ultramarine) blues, set off by touches of red and the colder and brighter whites, linking together the two portraits with a more curvy movement.