The “Sonnets in colour” series is moving to my general painting blog, here. The background stories published here will be soon moving my portfolio website. There will be no updates on this blog.

Author Archives: Lena Levin

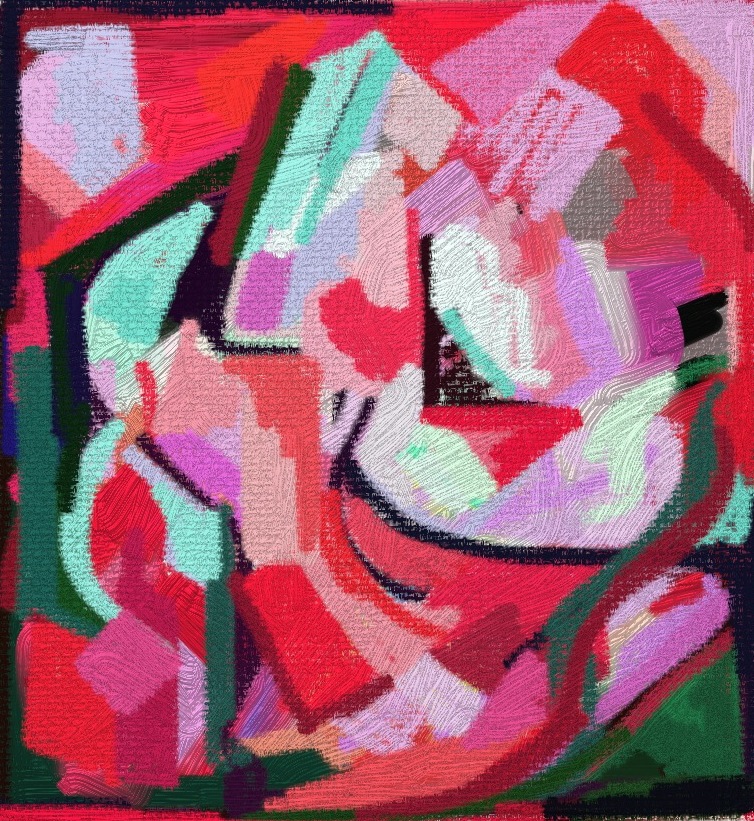

Sonnet 35: Such civil war is in my love and hate

Have you ever engaged in a heated internal dialogue with someone who has hurt you, or that’s how you feel anyway? When you are convinced that you try to excuse them, bringing in all kinds of rational reasons to do so, and yet feel that you are sinking deeper and deeper into a cyclic, aggressive dialogue… with whom? Is it still that person? Or is it you yourself? Defending yourself from the wound, or mounting an attack against yourself?

That’s what this sonnet is about, so read it with me, and we’ll see how Shakespeare deals with this, witnessing these struggles within himself and distilling them into a poem. As Anna Akhmatova once wrote, if only you knew what junk poems grow from…

No more be grieved at that which thou hast done:

Roses have thorns, and silver fountains mud,

Clouds and eclipses stain both moon and sun,

And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud.

The first quatrain: on its surface, a sensible, reasonable voice of forgiveness. And yet, it’s filled with platitudes, with borrowed, commonplace arguments, way too proverbial to sound genuine. What’s more, the friend’s unnamed fault is actually growing worse with every added metaphor, so that the thorn of the first one transforms into the loathsome canker of the last.

This quatrain forms the first layer of the painting’s structure: a bouquet of red roses, as banal and commonplace depiction of love as can be.

All men make faults

– so begins the second quatrain, seemingly continuing in the same vein of proverbial excuses.

But notice the verb, make: the neutral way way to continue would be “all men have faults”; this contrast between the actual and the expected, a first hint that the speaker of the sonnet begins to grasp that he is in the process of making, or at least exaggerating, his friend’s fault. But he furiously turns this insight into a passionate accusation against himself for defending the friend, mounting participle after participle in a chaotic, frantic, disturbingly ambiguous syntax:

All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorizing thy trespass with compare,

Myself corrupting, salving thy amiss,

Excusing thy sins more than thy sins are;

There are several things to note here:

- First, “even” in the first line has a meaning slightly different than it would have in the modern English: it doesn’t imply that the speaker is least likely to be at fault, just emphasizes the turn of attention towards oneself.

- “Authorizing” in the next line should be stressed on the second syllable, to fit into the rhythm of the poem.

- And finally, and most importantly: the pronouns in the last line are highly controversial: in different editions of the sonnets, you will find all possible combinations of “thy”, “their” and “these” in both places. I prefer this version, “excusing thy sins more than thy sins are”, because it aligns best with the speaker’s analysis of his own internal conversation: the way he “excuses” the friend’s sins makes them into something more than they actually are.

All in all, by the end of the quatrain, the speaker is left more hurt, and his friend, more guilty, than they were at the beginning. The quatrain ends abruptly, as though from the lack of breath after climbing the staircase of participles. This quatrain’s frantic syntax gives my painting its overall rhythms and movement.

For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense..

Sense; a word which might just claim the first place in the world-wide championship for the most self-contradictory meaning, here highlighted by its opposition with sensual.

Does the speaker mean that what we have heard so far was the voice of reason, an intellectual construct opposed to sensuality? Would this reading be sensible? Or is it the same “sense” that forms the stem of “sensual”? His capacity to feel? One or all of his senses? Like a little crystal ball, this word pulls in and pushes out into plain sight all internal contradictions reflected in the poem.

In the painting, it translates into somewhat tortured attempt at plain black-and-white geometry, which breaks and transforms the space around the roses.

In the poem, the mention of “sense” triggers a chain of legal metaphors, an imaginary court in which nobody knows who is the defendant, who is the accuser, and, most conspicuously, who is the judge; but court proceedings aren’t strong enough a metaphor, and the quatrain ends in civil war within the speaker’s mind and soul:

For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense –

Thy adverse party is thy advocate –

And ‘gainst myself a lawful plea commence.

Such civil war is in my love and hate

That I an accessory needs must be

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me.

The last sentence of the sonnet crosses the structural boundary in the sonnet’s structure. And yet, the poem ends with a rather weak contrast between sweet and sour, which sounds almost like a (sour) reconciliation after everything we have heard. I am an accessory to my sweet thief: not because I defend him, but because I hurt myself even more than he did.

Here is Polly Frame reading this sonnet, although she does break its rhythms with stressing some words “properly”, but not like the poem wants them to be stressed. Or, you can read it yourself in full:

No more be grieved at that which thou hast done:

Roses have thorns, and silver fountains mud,

Clouds and eclipses stain both moon and sun,

And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud.All men make faults, and even I in this,

Authorizing thy trespass with compare,

Myself corrupting, salving thy amiss,

Excusing thy sins more than thy sins are;For to thy sensual fault I bring in sense —

Thy adverse party is thy advocate —

And ‘gainst myself a lawful plea commence.

Such civil war is in my love and hateThat I an ‘accessory needs must be

To that sweet thief which sourly robs from me.

A pause

Aside

There has been a long pause in this blog’s reports of my work on the sonnets series. On the surface, it’s just because we had been delaying a photo session: so, although there are many more completed sonnet paintings, I didn’t have a proper photo to share. But there is a deeper reason (isn’t there ever?): I’ve been feeling like I’ve lost track – not with the painting process per se, but with my writing about it here.

It seems I’ve fallen into the life-long habit of academic writing, which implies “proving”, justifying an original insight in the manner currently accepted within the corresponding academic discipline; making it compelling to one’s peers according to established conventions. Except almost neither of these words and concepts apply here: there is no discipline of translating poems into paintings; no conventions; and it is not remotely possible to make a painting compelling with words if it doesn’t stand on its own.

What’s more, it seems increasingly clear to me that this writing style wasn’t designed to reveal, but rather to hide, even (and primarily) from myself, the profound, overwhelming effect this endeavour has on me (or, as Shakespeare would have probably written, on my self), how it has been changing me. That’s exactly what I wanted to happen, but, apparently, I wasn’t prepared for the enormity of this effect. See, for this whole thing to make any sense, I had to let these sonnets deep inside, very deep indeed; and they are powerful poems. Still, after all these centuries, with more energy in them than there is in some human beings, it seems. And however far removed from my life’s outer circumstances the dramatic plot of this sequence, yet the themes they touch, the internal conflicts they lay bare – they are as essential and fundamental to me as they are to anyone; including you.

This basic truth is one of the major motivations behind this series, and the writing on this blog can only be meaningful inasmuch as it brings it closer to you. But, as it seems, I am having a hard time internalizing this truth myself; maybe because these poems are telling me more about my self than I am quite prepared to acknowledge? I am not quite sure. One thing is clear, though: I have to resolve this whole thing within before I can find a new, more authentic, approach to writing here; and it’s much more important than to keep a regular schedule.

I honestly don’t know how long it will take. It maybe that I will write about the next sonnet tomorrow. Or maybe I will delay it till the pre-birthday process of taking stock of my life is over (the process which is more profound this year than it had ever been before): then it will be after April 13. Or even after Shakespeare’s birthday…? I frankly don’t know anything except this: if I am to write about this, it has to be done as genuinely, authentically, openly as the sonnets call for. I have to give it my all, and I will: I just have to figure out how…

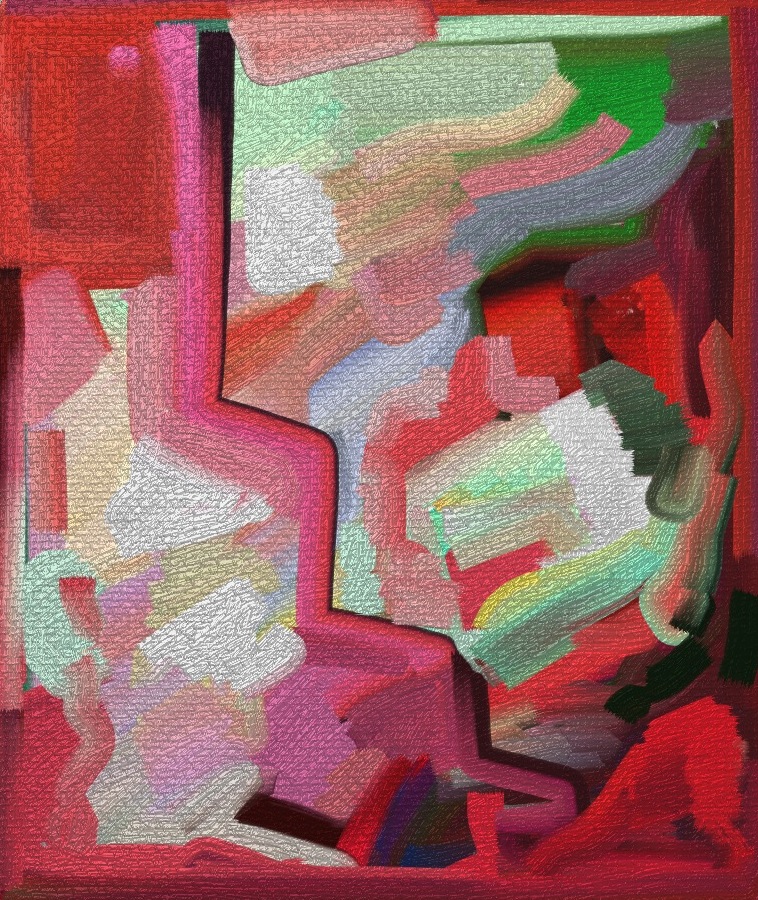

Sonnet 40 (Lascivious grace): first explorations in colour

As this long-term project evolves, I’ve decided to change the format of this blog, to open up the process of “translation”, to try and record it as it happens.

As this long-term project evolves, I’ve decided to change the format of this blog, to open up the process of “translation”, to try and record it as it happens.

One of the first steps of this process is a “colour scheme” for a sonnet, the very first attempt to re-think and re-feel the sonnet in terms of colour. I used to make them as oil sketches; beginning with Sonnet 40, I am trying something new: digital colour schemes (these two have been done in ArtRage for iPad).

Here is the sonnet itself, a cry of pain for betrayed love:

Take all my loves, my love, yea take them all;

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call;

All mine was thine, before thou hadst this more.

Then, if for my love, thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee, for my love thou usest;

But yet be blam’d, if thou thy self deceivest

By wilful taste of what thyself refusest.

I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief,

Although thou steal thee all my poverty:

And yet, love knows it is a greater grief

To bear love’s wrong, than hate’s known injury.

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites yet we must not be foes.

Below is the second colour scheme. At this point, I still have a very foggy view of the future painting, but the first step towards it is made.

Sonnet 34: It’s not enough that through the cloud thou break

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 34

Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day,

And make me travel forth without my cloak,

To let base clouds o’ertake me in my way,

Hiding thy bravery in their rotten smoke?‘Tis not enough that through the cloud thou break,

To dry the rain on my storm-beaten face,

For no man well of such a salve can speak,

That heals the wound, and cures not the disgrace:Nor can thy shame give physic to my grief;

Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss:

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offense’s cross.Ah! but those tears are pearl which thy love sheds,

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

Adetomiwa Edun reading this sonnet

This sonnet continues the theme, and the metaphor, of the previous one, equating the beloved with the sun, and the betrayal, with “base clouds”. Yet the second quatrain begins an explicit transfer of metaphors to the domain of humanity, replacing the sun-covered-by-clouds metaphor with a string of “human” ones, with the betrayal of love compared, in quick and somewhat confusing (and confused) succession, with illness, wound, disgrace, shame, pain, criminal offense, and punishment. Nothing the beloved does can heal the pain of betrayal or compensate for the speaker’s loss – except for tears.

And so, the despair of the body of the sonnet is resolved by sadness in its couplet, its pearly tears.

My translation into painting acknowledges the gradual change of metaphors from cosmic to personal, from rain to tears, in its highly schematic human figure, turning away, dejected, from the sun breaking through the cloud. Yet the essence of this translation is in colour, in its interplay of cold greys, blues, and muted magentas – from stormy clouds to pearly tears – from despair to sadness.

Sonnet 33: Heavenly alchemy

Lena Levin. Sonnet 33: Heavenly Alchemy. 20″x20″. Oil on linen. 2012

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 33

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain-tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy;Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face,

And from the forlorn world his visage hide,

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace:Even so my sun one early morn did shine

With all triumphant splendor on my brow;

But out, alack! he was but one hour mine,

The region cloud hath masked him from me now.Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth;

Suns of the world may stain when heaven’s sun staineth.

Adetomiwa Edun reading this sonnet

This sonnet opens a very direct and straightforward way of translation into painting, because it “pretends” to be just a landscape over the first two quatrains. The landscape appears first not as a metaphor, but just as a landscape, albeit described in somewhat heavenly and anthropomorphic language; only in the third quatrain, the metaphor is reversed, so the landscape turns out to be a strategy of dealing with human emotions.

Lena Levin. Tomales Bay: sunrise effects. 18″x24″, oil on linen. 2012

Lena Levin. Alameda: Rain and Sun. 24″x12″. Oil on canvas panel. 2011.

To be more precise, there are two landscapes here, or a single one under different lighting conditions. This ease in combining two or more temporal planes in a poem is often a challenge for a painting translation, but it was easier here: as a plein air painter working in Northern California, I am quite accustomed to painting changing lighting conditions within a single picture frame (and a single plein air session). I include here two paintings from such plein air sessions, which served as the most direct visual anchors for this sonnet painting.

But I knew, from the very beginning, that just a landscape with mixed lighting conditions wouldn’t be enough here. The painting would have to combine a representation of a morning, both sunny and cloudy at the same time, with a decidedly non-representational curvy movement of blues across the painting, a soul in pain of forlorn love.

Working on the landscape itself, I lost the blue curve for a while, and even decided, at one point, that it was a mistaken illusion of my preliminary vision. And yet I couldn’t complete the painting before the “abstract” movement of blues from the bottom of the picture plane towards the sky re-appeared.

Sonnet 32: Had my friend’s Muse grown with the growing age

Sonnet 32: Had my friend’s news grown with the growing age. 20″x20″. Oil on linen. 2012

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 32

If thou survive my well-contented day,

When that churl Death my bones with dust shall cover

And shalt by fortune once more re-survey

These poor rude lines of thy deceased lover,Compare them with the bettering of the time,

And though they be outstripped by every pen,

Reserve them for my love, not for their rhyme,

Exceeded by the height of happier men.O! then vouchsafe me but this loving thought:

“Had my friend’s Muse grown with this growing age,

A dearer birth than this his love had brought,

To march in ranks of better equipage:But since he died and poets better prove,

Theirs for their style I’ll read, his for his love”.

Sam Alexander reading this sonnet

This is an interesting sonnet, worth re-reading to every person in the clutches of self-doubt: Shakespeare imagining a future after his death, where the “style” would progress so far that his poems would only be worth re-reading to his friend for their content (“love”), not for “their rhymes”. And it’s Shakespeare we are talking about, after all…

The painting combines an eclectic selection of books with an eclectic selection of styles, from near-realism, via impressionism, and towards bits of Mondrian in the background, as a commentary on “progression of styles”. All the stylistic play in the background notwithstanding, the still life still retains the suggestion of crowded, somewhat messy, writing desk of a scholar and reader, who might have paused with a glass of wine for a minute, to remember his deceased lover and his love distilled into rhymes.

The books are, from left to right:

Helen Vendler’s “The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets” and Dante’s Divine Comedy on top of it. An open book of Rembrandt’s drawings and my sketchbook partly covering it. Stephen Greenblatt’s “Hamlet in Purgatory” and T.J. Clark’s “The painting of modern life” with a fragment of Manet’s “Argenteuil” (1874) on its cover.

Reading this poem from the future, a future far beyond the one imagined by Shakespeare, it opens an an avenue for fascinating run of imagination: what would have happened, indeed, had Shakespeare’s Muse grown with the growing age? And yet, I just watched yesterday Ralph Fiennes’ 2011 movie version of “Coriolanus”, set up with tanks, and automatic guns, and whatnot, “in the place they call Rome”; a growing age still fully in the power of this rather extraordinary muse.

An interview about my sonnets series

Aside

In lieu of this week’s painting post, here is my lengthy answer to Shauntelle Hamlett’s question in her “One Question Interviews” series. With her one question, Shauntelle had given me the push I needed to write down the whys and wherefores of this audacious enterprise…

Third collage

Image

Sonnets in colour III: Shakespeare 19-34, 80″x80″

This is the third – how should I call it? – building of sonnet paintings, corresponding to sixteen sonnets, from 19 to 34. The first two structures were smaller, 60″x60″ (nine sonnets each). All in all, there will be ten 3×3 (60″x60″) squares and four 4×4 (80″x80″), to complete the sonnet series. Just fourteen large paintings, no more, but still a long, long way to go.

Sonnet 31: Thou art the grave where buried love doth live

Sonnet 31: Thou art the grave where buried love doth live. 20″x20″. Oil on linen

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 31

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts

Which I by lacking have supposed dead,

And there reigns love and all love’s loving parts,

And all those friends which I thought buried.How many a holy and obsequious tear

Hath dear religious love stolen from mine eye

As interest of the dead, which now appear

But things removed that hidden in thee lie!Thou art the grave where buried love doth live,

Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone,

Who all their parts of me to thee did give;

That due of many now is thine alone:Their images I loved I view in thee,

And thou, all they, hast all the all of me.

Kate Fleetwood reading this sonnet

As a romantic address, it is a strange poem, isn’t it?

Although apparently an expression of love, the beloved is strikingly absent from the speaker’s world view. Maybe not absent, but transparent (transparent enough for the speaker to see all his lovers gone within); a vessel devoid of its own content, but filled with the speaker’s love and loving parts; cherished not for himself, but as love’s burial place.

For all its strangeness, we must admit the truth and almost involuntary honesty of it: isn’t this how romantic love works, filling (or replacing) its object with the lover’s imagination, seeing only one’s own emotions instead of the human being towards whom they are supposed to be directed? Loving one’s own love, rather than one’s beloved?

Even if we take this as a straightforward expression of the strength of the speaker’s feelings, which revive for him all his past loves in the person of his present one, the central metaphor of the poem is still decidedly strange. Thou art the grave where buried love doth live? Can you imagine saying (or hearing, come to this) something along these lines as an expression of deepest love?

The image of burial place colours the whole sonnet in sadness and tears; it sounds like mourning, rather than a celebration of love revived; and the idea of buried love still living in its grave seems to have come from a ghost story, not from the story of resurrection.

Marc Chagall. The Green Violinist. 1924

There were two visual sources at the conception of this painting. The first one might come as a surprise to you: it’s “The Green Violinist” by Marc Chagall. On the semantic level, this painting has a decidedly nostalgic quality, the rhythms and colours of mourning – if not for the lovers gone, then for the native land and family lost. On the formal level, it strikes me with the bold opposition between intense colours in the figure and the virtual lack of colour in the background: in spite of suggestions of landscape, the figure is placed as though in vacuum, in a space devoid of warmth, energy, matter.

What I’ve tried to do here is to revert this effect, while keeping the rhythms and overall colour harmony close to Chagall’s painting: that is to say, it’s now the figure that is virtually devoid of colour, warmth and matter – no more than slightest hints of the colours of its surroundings.

The second visual source is somewhat more vague, albeit more directly visible in the painting: some general impressions of cemeteries, pyramidal burial mounts, chapel windows. The figure is enclosed in a pyramid; it nearly is a pyramid (thou art the grave), albeit a transparent one, mirroring the rhythms of life around it.