William Shakespeare. Sonnet 34

Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day,

And make me travel forth without my cloak,

To let base clouds o’ertake me in my way,

Hiding thy bravery in their rotten smoke?‘Tis not enough that through the cloud thou break,

To dry the rain on my storm-beaten face,

For no man well of such a salve can speak,

That heals the wound, and cures not the disgrace:Nor can thy shame give physic to my grief;

Though thou repent, yet I have still the loss:

The offender’s sorrow lends but weak relief

To him that bears the strong offense’s cross.Ah! but those tears are pearl which thy love sheds,

And they are rich and ransom all ill deeds.

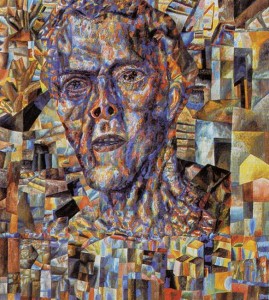

Adetomiwa Edun reading this sonnet

This sonnet continues the theme, and the metaphor, of the previous one, equating the beloved with the sun, and the betrayal, with “base clouds”. Yet the second quatrain begins an explicit transfer of metaphors to the domain of humanity, replacing the sun-covered-by-clouds metaphor with a string of “human” ones, with the betrayal of love compared, in quick and somewhat confusing (and confused) succession, with illness, wound, disgrace, shame, pain, criminal offense, and punishment. Nothing the beloved does can heal the pain of betrayal or compensate for the speaker’s loss – except for tears.

And so, the despair of the body of the sonnet is resolved by sadness in its couplet, its pearly tears.

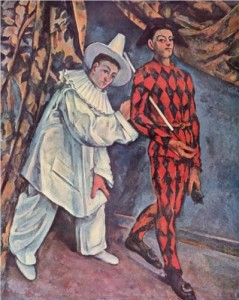

My translation into painting acknowledges the gradual change of metaphors from cosmic to personal, from rain to tears, in its highly schematic human figure, turning away, dejected, from the sun breaking through the cloud. Yet the essence of this translation is in colour, in its interplay of cold greys, blues, and muted magentas – from stormy clouds to pearly tears – from despair to sadness.