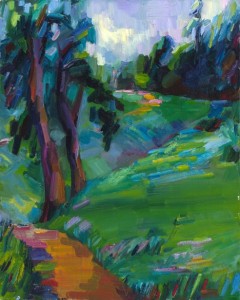

Sonnet 13: Against the stormy gusts of winter day and barren rage of death’s eternal cold. 20″x20″. Oil on linen. 2012

O, that you were yourself! but, love, you are

No longer yours than you yourself here live:

Against this coming end you should prepare,

And your sweet semblance to some other give.

So should that beauty which you hold in lease

Find no determination: then you were

Yourself again after yourself’s decease,

When your sweet issue your sweet form should bear.

Who lets so fair a house fall to decay,

Which husbandry in honour might uphold

Against the stormy gusts of winter’s day

And barren rage of death’s eternal cold?O, none but unthrifts! Dear my love, you know

You had a father: let your son say so.

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 13

Stephen Greenblatt writes, in his book “Will in the World” (W. W. Norton & Compan, 2004), about sonnet writing as a “sophisticated game of courtiers” (p. 234), which became fashionable in the reign of Henry VIII and was perfected in the reign of Elizabeth.

“The challenge of the game,” he says, “was to sound as intimate, self-revealing and emotionally vulnerable as possible, without actually disclosing anything compromising to anyone outside the innermost circle.” (ibid.) The further a reader is removed from the writer and the addressee of a sonnet, the more vague and incomprehensible references to any specific characters or facts must be.

This is the tradition I claim for this painting, and so this story is very short. The sonnet, I feel, achieves one the first powerful emotional peaks in the sequence, especially in the lines which I chose as the title for the painting; and this painting draws on deeply personal references, which don’t really need to be revealed explicitly. They will be recognized by my “innermost circle”, but not beyond.