In many sonnets, Shakespeare employs a specif visual impression, often a landscape, as an anchor, a visual embodiment of his meaning. For a painter on a quest like mine, a translation of poems into paintings, rhymes into colours, this presents both a relief and a special challenge.

The relief part should be obvious: it’s a path to imagery, which, albeit individual in its details, is universal enough for me to “ground” in my own visual impressions, which are the most immediate and “easy” painting material. This blog already contains a couple of paintings so grounded, most obviously this, “Sonnet 12″ painting. The challenge arises because Shakespeare doesn’t leave the intended “human”, emotional interpretation of the sonnet unnamed: we are told, more or less directly and in plain language, how exactly this particular imagery is linked to the sonnet’s meaning. A painter doesn’t really have this luxury, at least not within general stylistic constraints implicitly defining this project.

Consider Sonnet 33, which I am working on now. Its first two couplets seem completely devoid of personal feelings and dedicated to a (commonly seen) landscape:

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain-tops with sovereign eye,

Kissing with golden face the meadows green,

Gilding pale streams with heavenly alchemy;Anon permit the basest clouds to ride

With ugly rack on his celestial face,

And from the forlorn world his visage hide,

Stealing unseen to west with this disgrace.

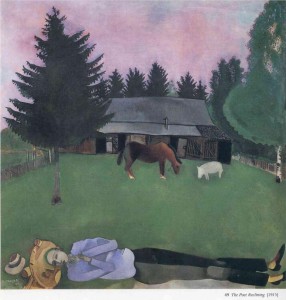

Strictly speaking, there are rather two landscapes here: one with the sun flattering the earth with his presence, the other with the sun unseen, hidden by the basest clouds. But that would be the least of my problems in a “painterly” representation of this poem: as Shakespeare notes, these lighting conditions can replace one another so fast (both in England and in Northern California) that a depiction of one can suggest another. I, for one, have several plein air paintings which play on a combination of both impressions,

this one, for instance:

But Shakespeare not only uses anthropomorphic vocabulary in his description of the landscape, he continues with a direct superimposition of human affairs onto the landscape just described, equating his beloved with the sun:

Even so my sun one early morn did shine

With all triumphant splendor on my brow;

But out, alack! he was but one hour mine,

The region cloud hath masked him from me now.Yet him for this my love no whit disdaineth;

Suns of the world may stain when heaven’s sun staineth.

The interpretation is not as straightforward as it might seem (I will return to it later, when I present my painting for this sonnet), but the fact remains: the identification between the sun and the beloved is stated as plainly and directly as possible.

But a fleeting temptation to do something like this in a painting (after all, it would be no problem to suggest a human face within a circle depicting the sun, or something to that effect), this fleeting temptation goes away as soon as we understand that this direct identification is not what makes the poem work. The genuine humanization of the landscape, its emotional interpretation, lies in the verse. And so a painter has to find the corresponding effects in the paint, in colours and lines.

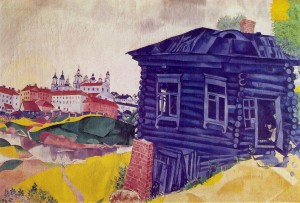

This brings me back to the Chagall painting with which this blog post somewhat enigmatically begins. Here it is again, a bit larger:

This is a landscape (or, to be more exact, a cityscape); in fact, quite a detailed depiction of specific visual reality: there is a town on the other side of the river, with churches and large buildings, separate from the river by a wall (but reflected in it), and a poorly wooden cabin on “our” side of the river, barely holding together (and even a person inside, if you look closely); you can even see every piece of timber and every brick.

There is no “literal” information in the painting that another interpretation might be intended, but it nonetheless leaves us in no doubt that it is not “just” a representation of some visual impression. This information is conveyed primarily by colour: the “real” colours are heightened and intensified to reach the six core components of the “colour wheel”: its dominated by three primary colours, blue, yellow and red (in that order), with an additional minor role played by three secondaries, green, violet, and orange (also in that order). No “reality” would ever look like this, but this depiction (or reinterpretation) seems convincing and harmonious nonetheless.

We know for a fact that, although a house can be blue, a log cabin like this cannot; this color is as unrealistic as the green of Chagall’s green cows and fiddlers. That this blueness is contrasted to all other colors of the rainbow in the surrounding landscape and to conspicuously dirty yellowish sky, tells us to search for a human, personal interpretation as clearly as though were instructed to do so by some sort of Shakespeare’s “even so” (as in the third couplet above).

We might differ in the exact emotional interpretation (and our interpretation might differ from Chagall’s intentions), but isn’t this the same in the poem: does the speaker of the sonnet accuse his lover of betrayal and disgrace (as suggested by the language of the first two quatrain)? Does he still idolize him as “the sun” (as in the third quatrain)? Does he remain philosophically neutral about it (as suggested in the couplet)? Probably all of this, and then more.