Sonnet 14: “Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck.” 20″x20″. Oil on linen. 2012

Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck;

And yet methinks I have astronomy,

But not to tell of good or evil luck,

Of plagues, of dearths, or seasons’ quality;

Nor can I fortune to brief minutes tell,

Pointing to each his thunder, rain and wind,

Or say with princes if it shall go well,

By oft predict that I in heaven find:

But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive,

And, constant stars, in them I read such art

As truth and beauty shall together thrive,

If from thyself to store thou wouldst convert;

Or else of thee this I prognosticate:

Thy end is truth’s and beauty’s doom and date.

Click here to listen to David Calder reading this sonnet in the Touchpress edition.

When I began composing this painting in my mind, I thought it would be some sort of comic relief from the previous, rather painful, one. After all, a large chunk of the sonnet is filled with mocking astrology (“astronomy” in Shakespeare’s language), listing common types of its mundane predictions and using markedly convoluted grammar to convey its pompous language.

(As an aside, a modern reader might be tempted to assume that the preposterous “oft predict” in line 8, where both words seem to have lost their part-of-speech affiliation in an attempt to sound more important, is just one more difference between Shakespeare’s English and modern English. This doesn’t seem to be the case: this phrase must have sounded as strange to contemporary readers as it does to us.)

Yet I could not quite find my way into the painting from the “mocking astrology” angle; the essence of the sonnet’s meaning lies elsewhere: another human being, “thou”, as the largest thing in the universe, brighter than the stars, the source of real knowledge.

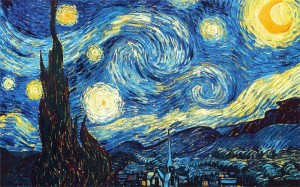

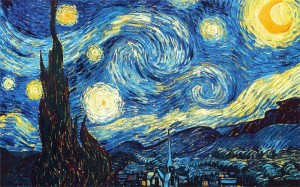

Vincent Van Gogh. The Starry Night. 73.7 x 92.1 cm. Oil on canvas. 1889.

I used Van Gogh’s Starry Night as a starting pointing for the painting. On the one hand, the original is one of the most powerful visual statements of insignificance of our little, negligible human affairs (reduced to the bottom of the painting) – in comparison to the ever-present influence of the stars above. On the other hand, the reproductions of this image are so ridiculously overused nowadays – it seems to be everywhere, from postcards to jigsaw puzzles to place mats and coffee cups – that its use in the context of our culture seems to match Shakespeare’s mock of popular mythology of his. My painting, therefore, tries to invoke both the original and its endless reproductions.

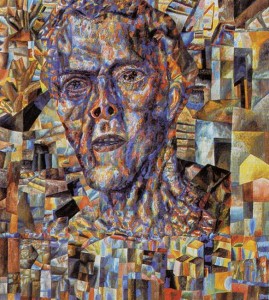

Mikail Vrubel. The Swan Princess. Oil on canvas. 142.5 x 93.5 cm. 1900.

The second image referenced in the painting is less universally known; it’s Mikhail Vrubel’s Swan Princess (1900). At this time, Vrubel was working on the set and costumes for a production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera, “The tale of Saltan the Tzar”; the Swan Princess was played by Vrubel’s wife, Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel (the opera itself is based on a tale-poem by Alexander Pushkin). It might not be clear from this image (please click it to see a larger one), but the Swan Princess has a star shining from her forehead, which is, I believe, what “attracted” her into my painting.

The semantic contrast between unimportant things astrologists claim to predict and the answers to the essential, eternal questions to be found in the beloved’s eyes is formally enacted in the sonnet via the opposition of rhythms in the first eight lines and in the last six. Just pronounce to yourself and compare two “parallel” opening lines, line 1 and line 9:

Not from the stars do I judgement pluck…

But from thine eyes my knowledge I derive…

Feel how the scurrying rhythm of the first line is replaced by a slower and more powerful movement of the second one? This is the contrast I’ve tried to “recreate” in the painting, in the opposition between its “starry” part and the “swan princess” part. And both the chaotic movement of heavenly stars and the vertical spire of the church below ultimately lead the viewer to the constant stars that are human eyes.

And yet, in the end, it did turn out to be a whimsical and mocking painting, yet not quite as I imagined it at first.

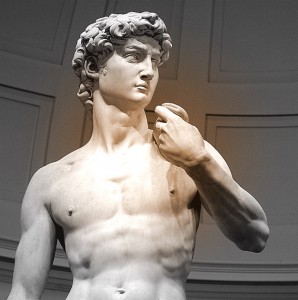

The reference point for this translation is, of course, Michelangelo’s David – the image inevitably suggested by the very concept of “beauty’s pattern to succeeding men”, by the mention of carving, and, last but not least, by the powerful, truly timeless, rhythm of the third quatrain.

The reference point for this translation is, of course, Michelangelo’s David – the image inevitably suggested by the very concept of “beauty’s pattern to succeeding men”, by the mention of carving, and, last but not least, by the powerful, truly timeless, rhythm of the third quatrain.