Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly?

Sweets with sweets war not, joy delights in joy.

Why lovest thou that which thou receivest not gladly,

Or else receivest with pleasure thine annoy?

If the true concord of well-tuned sounds,

By unions married, do offend thine ear,

They do but sweetly chide thee, who confounds

In singleness the parts that thou shouldst bear.

Mark how one string, sweet husband to another,

Strikes each in each by mutual ordering,

Resembling sire and child and happy mother

Who all in one, one pleasing note do sing:

Whose speechless song, being many, seeming one,

Sings this to thee: ‘thou single wilt prove none.’

Click here to listen to Prasanna Puwanarajah’s reading of this sonnet.

A light and whimsical poem, making a somewhat preposterous argument: that the young man’s failure to enjoy music he hears is due to a similarity between music and marriage (which he rejects, as ever); and invoking a more recurrent theme of Shakespeare’s, the relation between music and love. For some reason, this was the first sonnet that I genuinely “saw” as a painting, albeit not as clearly and distinctly as now, when the painting is complete.

The semantic motive I picked for this painting is central to the poem: the contrast between harmonious multiplicity (unified into oneness) – represented by the music, and singleness (turning into none-ness) – represented by the stubborn young man. This motive, I decided, would be enacted in painting almost entirely via colour, with a structured interplay of colours in the background opposed to the nearly black-and-white figure, which would thus optically recede into non-existence; almost as though it were not a human figure, but rather a hole cut out in the “musical” background.

Even with my primary focus on colour, I needed a figure, a gesture – something which would be easily “read” by the viewer’s eye as a young man listening to music with sadness and displeasure. In my mental search for this gesture, I recalled a scene – written, unsurprisingly, by the same author – which spells out the drama of the sonnet in somewhat more detail: the scene of Benedick listening to a song in “Much Ado About Nothing”. Here is this scene from the movie directed by Kenneth Branagh:

Whether you have clicked to play the scene or not, I hope you have noticed the source of the figure in my painting: Benedick’s (played by Kenneth Branagh) posture (even though I have always loved this movie, I was surprised by the remarkable painterly quality and expressiveness of this scene, which “translated” itself into a painting with natural ease). Here is my first attempt to sketch the future painting. Yet even for this smaller size, the colour vs. black-and-white opposition wasn’t clear enough and the multiplicity of colours in the background wasn’t structured enough to fully realize the original idea.

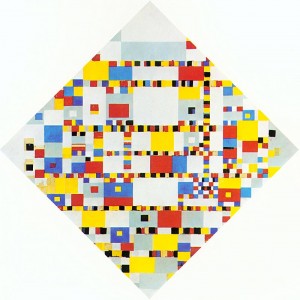

Piet Mondrian. Victory Boogie-Woogie. 1943/44 (unfinished). Oil and paper on canvas, diagonal 177.5 cm.

The final inspiration for composing the background – both colourful and musical – came from Piet Mondrian’s geometry of colours. Although there is really no single reference image for this inspiration, I include his last, unfinished, painting, with a fleeting feeling of hope given by continuity of ideas in the face of artist’s work interrupted by barren rage of death’s eternal cold. Not only did Mondrian’s seemingly tight geometry give me the freedom to make the background I needed for the overall composition – it also allowed for minor adjustments in “translation”. For instance, Shakespeare’s enactment of presumed disharmony in the young man’s rejection of music, in clashing rhythms and sounds of the first quatrain, transformed into the lines clashing into smaller multicolored rectangles near the young man’s face.