One of the paradoxes of painting I’ve been struggling with in 2016 is this: as a pathway of personal transformation (a “creative outlet”, as they say), it is more alive, relevant, and important now than it has ever been. But as a vehicle for sharing experiences, it may well be outdated — rather dead than alive.

Let me spell this out in some more detail. The power of painting as an outlet for inspiration is two-fold. First, it can be pursued unstudied: the process of painting can be enlightening, and transformational, and exhilarating even for absolute beginners (after all, any child would draw and paint if given half a chance). In fact, it might be easier for beginners to make this process meaningful (I don’t remember who said that painting is easy when you don’t know how, but I think they were absolutely right). It is not like playing piano (let alone violin), where most of us need to practice a lot before even glimpses of meaning might emerge.

On the other hand, painting is a very embodied, sensory, even sensual experience, which takes the human being outside the habitual confines of mind and language (to paint a thing is to forget its name). It is a space where mind and language just have to give up, to surrender to something unsayable — and this is exactly what is badly needed to those of us who (like me), are accustomed to living mainly “in their head”, in the grips of illusion that language is the ultimate (if not the only) means of understanding reality. And in our day and time, there are probably more such people than ever before.

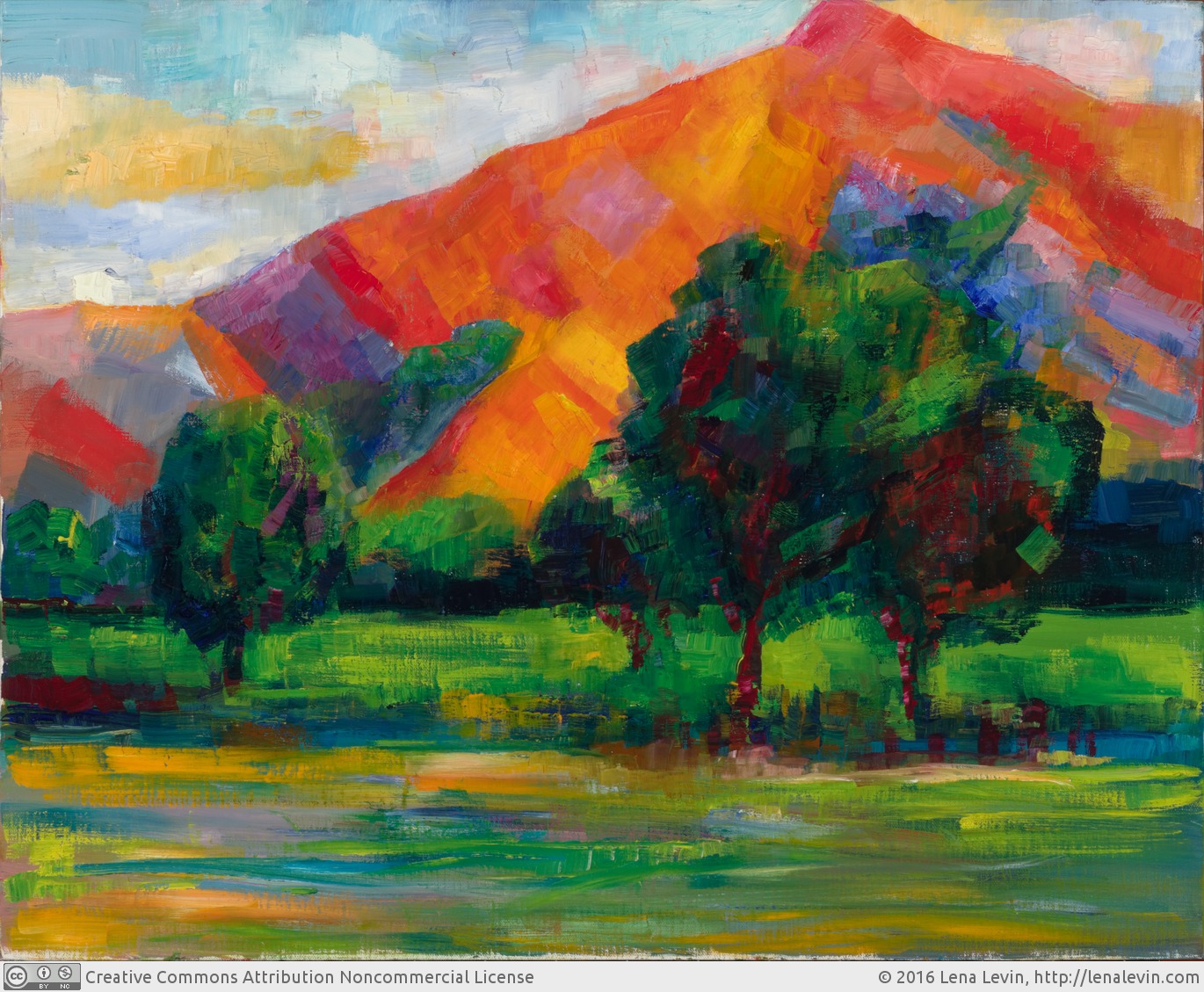

So painting as a process — painting as a kind of seeing meditation — has an important part to play in today’s world. Painting understood as an art of seeing.

But what about painting as an art of showing? As a way of sharing visual (and/or inner) experiences? This power seems to be dwindling, barely alive. I spent a huge chunk of my time and energy last year struggling to accept this and examining all kinds of potential social and cultural culprits (and I really don’t want to return to these topics right now).

The deeper cause of this dwindling might lie, I believe, in the intrinsic timelessness of painting: like no other art form, a painting creates a space within which there is no time.

A poem, a story, a sonata, a song — in their different ways, but they all have their own inner time, and a locus in the “outer”, objective time. They begin, they take you into their inner rhythm, and then they end. Even a sculpture invites the spectator to move around it, and so creates a certain flow of time around itself. But painting? There is no time; pure timelessness and stillness, and no intrinsic limits on how much time the spectator would spend in front of it. Because of this, the process of looking at painting — listening to it — perceiving it — may be much more demanding than the process of making a painting. Much more uncomfortable and unsettling to a modern human, steeped as we are in the fast-moving imagery of movies and social media feeds.

I spent some time last year studying different ways museums use to try and reconnect spectators with paintings, and they all seem to involve adding some action to the process of looking (drawing, writing, talking even some bodily actions). And I, too, love to merge the process of looking at a painting with the process of painting. But in the final analysis, isn’t it all about removing this deep discomfort of pure stillness from the space of a painting?

But isn’t stillness exactly what we need? Do we really want to alleviate this discomfort?