William Shakespeare. Sonnet 25

Let those who are in favour with their stars

Of public honour and proud titles boast,

Whilst I, whom fortune of such triumph bars,

Unlooked for joy in that I honour most.Great princes’ favourites their fair leaves spread

But as the marigold at the sun’s eye,

And in themselves their pride lies buried,

For at a frown they in their glory die.The painful warrior famoused for fight,

After a thousand victories once foiled,

Is from the book of honour rased quite,

And all the rest forgot for which he toiled:Then happy I, that love and am beloved

Where I may not remove nor be removed.

Noma Dumezweni reading this sonnet.

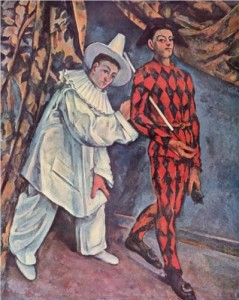

The central image of this translation is taken directly from the most visual metaphor of the sonnet: a somewhat abstract representation of marigolds in the sun’s eye. The overall joyful colour scheme of the painting reflects the speaker’s expressed joy in his private happiness in love, contrasted, in its supposed permanence, to fleeting triumphs and public honour.

But just as the speaker of the sonnet boasts in the couplet about his presumed independence of the stars, its author knows full well that the private bliss of romantic love can be just as fleeting as public triumphs (and in the dramatic sequence of the sonnets, this turn of events is just around the corner). To boast that one can hide from the stars, is, as Helen Vendler puts it, “the most foolish boast of all”, and this meaning would be evident to Renaissance readers (Helen Vendler. The Art of Shakespeare Sonnets, p. 145).

So, while being held together by rhythms and rhymes, the sonnet’s argument crumbles and falls apart and, in a sense, buries its pride in itself. This is what I was after in this translation: being held together by colour, the picture plane seems about to fall apart structurally; and although the loss of joyful colors seems to be concentrated in the bottom third of the painting, it is also present within the spreading marigolds themselves. The self-destructive quality of the painting stands both for the deceptive nature of stars’ favours and for the speaker’s attempt at self-deception in the couplet.