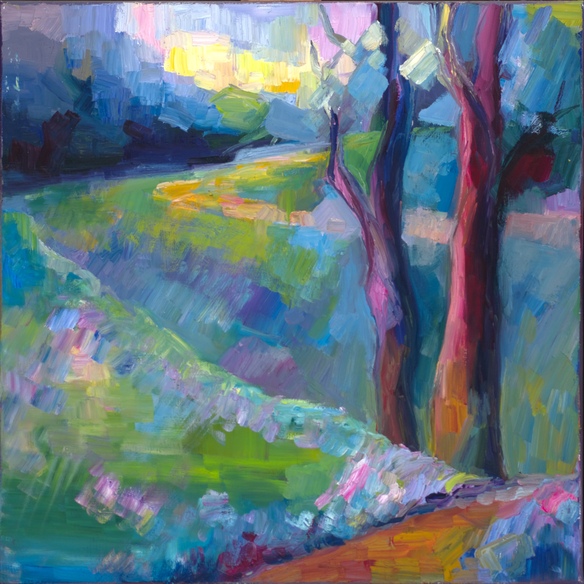

Sonnet 21: A couplement of proud compare. 20″x20″. Oil on linen. 2012.

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 21

So is it not with me as with that Muse

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse,

Who heaven itself for ornament doth use

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse,

Making a couplement of proud compare,

With sun and moon, with earth and sea’s rich gems,

With April’s first-born flowers, and all things rare

That heaven’s air in this huge rondure hems.

O let me, true in love, but truly write,

And then believe me, my love is as fair

As any mother’s child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven’s air:

Let them say more that like of hearsay well;

I will not praise that purpose not to sell.

Tunji Kasim reading this sonnet

This is a sonnet about poetry, and so my painting is about painting.

The sonnet contrasts two kinds of poetry, the true and authentic poetry inspired by love, vs. the false and exaggerated poetry based on hearsay. True to himself, Shakespeare enacts poetry of the latter kind within the sonnet and then “corrects” it; this juxtaposition is highlighted by repetition of rhyme-words and rhyme-sounds of poem-within-poem in the “real” poem (in violation of general rules of Italian sonnet righting [Vendler 1997: 131]). So the overall concept of this translation into painting was rather straightforward: there had to be a contrast between the painting and a painting-within-painting.

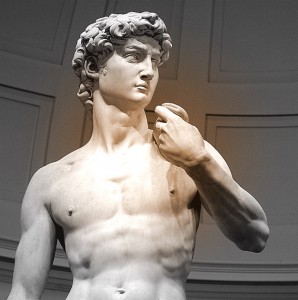

Lena Levin. Unbearable strangeness. 12″x12″. Oil on linen panel. 2012

My first approach to this idea involved a juxtaposition of three stylistic versions of approximately the same still-life set up (with a nearly hidden internal reference to a painting of Adriaen Coorte’s. This sketch (now called “Unbearable strangeness) is shown on the left. It didn’t quite work.

To begin with, while concentrating on the contrast between how things are compared by different Muses, I’ve lost the contrast between what they are compared with, essential in the sonnet: the false poetry compares love and beloved with every fair and rare thing on earth and in heaven, the true poetry remains on the earthly level of humanity (any mother’s child). Secondly, I have lost the key (word) of heaven (repeated in every quatrain of the sonnet) as the ultimate standard of comparison, both in the colour harmony and in the (lack of) vertical movement within the “real” areas of the picture plane. It also turned out that repeating the same set-up in a painting-within-painting creates an ambiguity between a painting and a mirror, which doesn’t align with the poem’s meaning.

Therefore, the final painting approaches the same idea in a different way. Most importantly, there is now heaven with gold candles in its air instead of one of still-life versions: it opens up this “chamber” painting into a larger universe and defines both the vertical dimension of the painting and its overall color harmony.

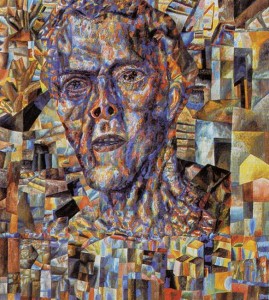

Willem Kalf. Still life with silver jug. 73,8 x 65,2 cm. Oil on canvas. 1655-57

Secondly, the subject matter of the “real” still life and of the painting-within-painting is now different: the real one, with bread and onions is decidedly more earthly, the “painted” one, with its lemons, silver and china, more exotic and “fine” (rare and fair). I did, however, retain one common element, the wine glass, for the sake of purely stylistic contrast and to acknowledge the repetition of rhymes in the sonnet.

There is another important difference as well: in the first study above, all three versions of the still life were done from life; here, the painting-within-painting is borrowed from several still life paintings of the Dutch Golden Age (I show here the one most explicitly referred to in my work, by Willem Kalf). This introduces the visual counterpart of “hearsay” in the poem: the rival poets don’t invent their hyperbolic comparisons themselves, but borrow them from others (stirred by a painted beauty).

There are two other, purely visual, contrasts between the two still life areas:

- Geometrically, the painting-within-painting is a vertical plane (corresponding to “vertical” metaphors condemned in the sonnet), whereas the “real life” set-up is horizontal, earth-bound, almost falling out of the picture plane towards the viewer;

- Colour-wise, the painting-within-painting borrows its colour harmony from the heaven area and intensifies it as far as possible, that is, heaven itself for ornament doth use. In contrast to this, the real-life area of the painting is saturated with earthly reds and ochres.

All in all, it turned out that a humble still life can offer ample opportunities for creating visual counterparts for a poetic commentary on poetry.

References:

Helen Vendler. The Art of Shakespeare Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts &ndahs; London, England. 1997.