William Shakespeare. Sonnet 29

When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries

And look upon myself and curse my fate,Wishing me like to one more rich in hope,

Featured like him, like him with friends possessed,

Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope,

With what I most enjoy contented least;Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,

Haply I think on thee, and then my state,

Like to the lark at break of day arising

From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate;For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings

That then I scorn to change my state with kings.

Patrick Stewart reading this sonnet

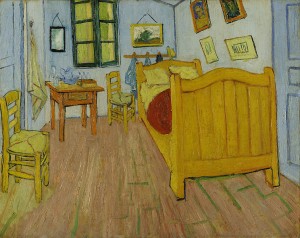

The composition of this painting is derived from an amalgamation of two classical images, Vincent Van Gogh’s bedroom in Arles (left) and Marc Chagall’s “The Birthday” (below). There is an obvious similarity in subject matter between two paintings: we see a barely furnished room of a poor man, distinctly in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes, the room of the artist himself. Apart from the subject matter as such, there is this distinctly claustrophobic geometric grid of the mundane in both of them, and similarly skewed perspectives in how this environment is represented.

There is also, of course, the striking difference created by the presence vs. absence of love: Chagall’s beloved Bella is there in his room, and so he depicts himself like to the lark at break of day arising; Van Gogh’s is a solitary room of an outcast and hermit. In the geometry of Chagall’s composition, love disrupts the angular skewed grid with a graceful curve, which nearly carries the artist to heaven’s gate, out of the picture plane — there are no curves, not even a hint of an upward movement, in Van Gogh’s composition.

This is precisely the contrast that creates the tension of Shakespeare’s sonnet, which breaks the rhythmic grid of the first two quatrains with a slow, graceful upward movement in the third. Except, of course, it’s not an appearance of the beloved that creates this change: the speaker’s imagination, a mere thought of the beloved, is enough. And that’s why I don’t introduce any floating figures in the composition. Instead, the grid of the room is broken by an upward outburst of abstract brushstrokes.

The viewer, however, is invited to float together with the author, insofar as the perspective of the room suggests that it’s viewed from above, by someone whose imagination has just lifted him up from solitary confinement behind the writing desk, alone with his books and his drink.