William Shakespeare. Sonnet 23

As an unperfect actor on the stage,

Who with his fear is put beside his part,

Or some fierce thing replete with too much rage,

Whose strength’s abundance weakens his own heart;So I, for fear of trust, forget to say

The perfect ceremony of love’s rite,

And in mine own love’s strength seem to decay,

O’ercharged with burthen of mine own love’s might.O! let my looks be then the eloquence

And dumb presagers of my speaking breast,

Who plead for love, and look for recompense,

More than that tongue that more hath more expressed.O! learn to read what silent love hath writ:

To hear with eyes belongs to love’s fine wit.

Niamh McGrady reading this sonnet.

A funny thing about this sonnet is that nobody seems to be sure whether it’s looks or books that are supposed to be the speaker’s eloquence and dumb presagers; each publisher and commentator decides for themselves. I give here, in effect, both options: the text above features looks, and in the Touchpress edition I link to for Niamh McGrady’s reading, it’s books. Personally, I suspect that, with all the play on reading the signs of silent love going on in the sonnet, Shakespeare might have planned our confusion.

Be it as it may, for the medium I am translating sonnets into, looks are, beyond doubt, more relevant. The key words, which anchor this translation, are dumb presagers of my speaking breast (that is, the actors of introductory pantomime plays, common in Shakespeare’s time – as shown to us in Hamlet‘s “play within play”).

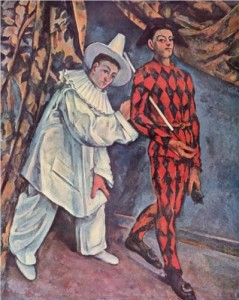

Visual anchors for this painting are various depictions of Commedia dell‘Arte actors in paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, particularly Pierrot, of course.

In a sense, this painting references multiple variations on this general motive, but I include here only two which seem to me most essential, Paul Cezanne’s “Mardi Gras” (1988) (above) and Salvador Dali’s “Pierrot playing the Guitar” (1925) (right).

The three figures in my painting could be read both as three “dumb presagers” or as three versions of the same character, vacillating between being too strong and fierce and too fearful and imperfect, and so remaining silent. This contrast, central to the poem, is also reflected in differences in treatment of various parts of the picture plane: from flat on the right to overcharged with brushwork on the left.