When I do count the clock that tells the time,

And see the brave day sunk in hideous night;

When I behold the violet past prime,

And sable curls all silver’d o’er with white;

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard,

Then of thy beauty do I question make,

That thou among the wastes of time must go,

Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake

And die as fast as they see others grow;

And nothing ‘gainst Time’s scythe can make defense

Save breed to brave him when he takes thee hence.

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 12

Click here to listen to David Tennant reading this sonnet.

In this first “procreation” sub-sequence of his sonnets sequence, Shakespeare often invokes a kind of double vision, “double exposure” in modern terms.

Most often, the speaker of the sonnets looks at something blooming and green, but sees, simultaneously or instead, its future decay. Here, this double vision is reversed, in the way both more optimistic – despite the mournful couplet – and closer to my own world view: he looks at things past prime, at a wintery landscape, yet keeps in his mind’s eye their greener beauty and former glory.

I love this poem – the rhythm of its first lines sounding exactly like the clock that tells the time, and its clearly defined colour harmony: violets and greens all silvered over with white. On the surface of it, the “silvered over with white” attribute applies to sable curls only, but an attempt to translate the poem into painting reveals its more general meaning, merging the silvery streaks in one’s aging hair with snow covering summer greens.

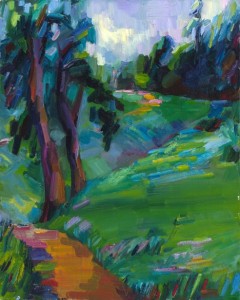

The poem connected itself in my mind with my own visual experience, recorded earlier in an en plein air study from Chabot park, on a day both green and rainy. The rhythm of time, in this painting, is identified with the diagonal rhythms of the hills, with a road going into the distance, sometimes disappearing behind the hills; the visual link is motivated by the swing of the pendulum.

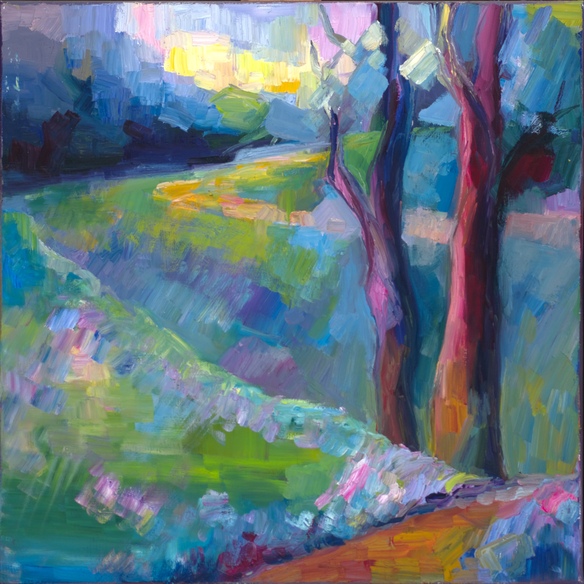

I changed the composition slightly, moving the violets around, silvering my greens all over with white, and making the trees more ambiguous as to whether they have lusty leaves or are barren of them; trying, in sum, to see the landscape with Shakespeare’s eye, which could see a summer and a winter, the beauty and the decay, at the same time.