Sonnet 31: Thou art the grave where buried love doth live. 20″x20″. Oil on linen

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 31

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts

Which I by lacking have supposed dead,

And there reigns love and all love’s loving parts,

And all those friends which I thought buried.How many a holy and obsequious tear

Hath dear religious love stolen from mine eye

As interest of the dead, which now appear

But things removed that hidden in thee lie!Thou art the grave where buried love doth live,

Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone,

Who all their parts of me to thee did give;

That due of many now is thine alone:Their images I loved I view in thee,

And thou, all they, hast all the all of me.

Kate Fleetwood reading this sonnet

As a romantic address, it is a strange poem, isn’t it?

Although apparently an expression of love, the beloved is strikingly absent from the speaker’s world view. Maybe not absent, but transparent (transparent enough for the speaker to see all his lovers gone within); a vessel devoid of its own content, but filled with the speaker’s love and loving parts; cherished not for himself, but as love’s burial place.

For all its strangeness, we must admit the truth and almost involuntary honesty of it: isn’t this how romantic love works, filling (or replacing) its object with the lover’s imagination, seeing only one’s own emotions instead of the human being towards whom they are supposed to be directed? Loving one’s own love, rather than one’s beloved?

Even if we take this as a straightforward expression of the strength of the speaker’s feelings, which revive for him all his past loves in the person of his present one, the central metaphor of the poem is still decidedly strange. Thou art the grave where buried love doth live? Can you imagine saying (or hearing, come to this) something along these lines as an expression of deepest love?

The image of burial place colours the whole sonnet in sadness and tears; it sounds like mourning, rather than a celebration of love revived; and the idea of buried love still living in its grave seems to have come from a ghost story, not from the story of resurrection.

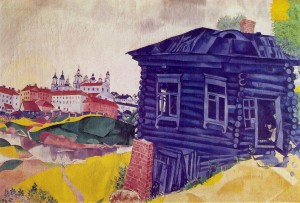

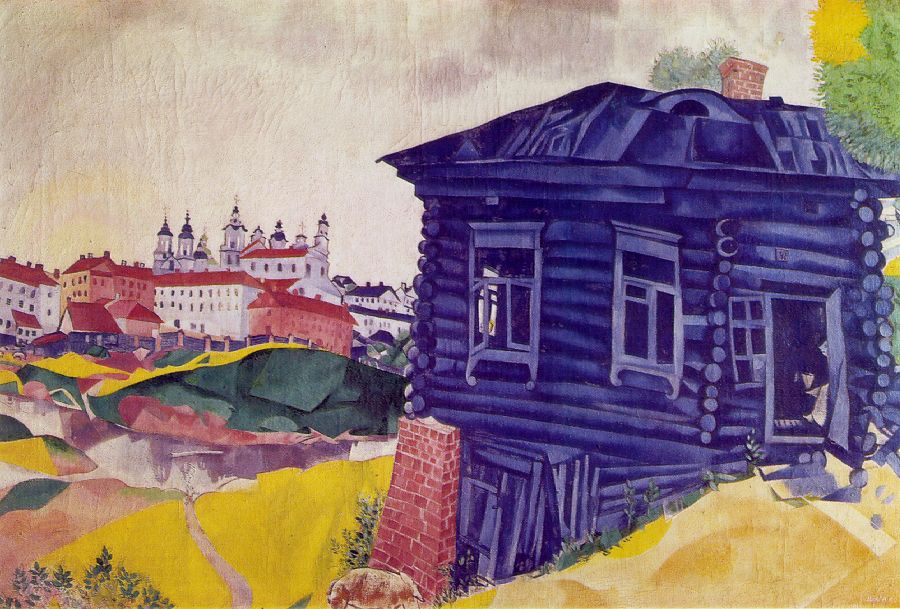

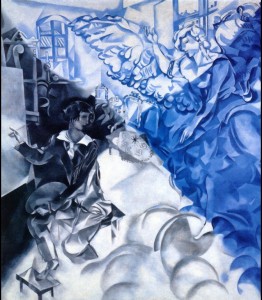

Marc Chagall. The Green Violinist. 1924

There were two visual sources at the conception of this painting. The first one might come as a surprise to you: it’s “The Green Violinist” by Marc Chagall. On the semantic level, this painting has a decidedly nostalgic quality, the rhythms and colours of mourning – if not for the lovers gone, then for the native land and family lost. On the formal level, it strikes me with the bold opposition between intense colours in the figure and the virtual lack of colour in the background: in spite of suggestions of landscape, the figure is placed as though in vacuum, in a space devoid of warmth, energy, matter.

What I’ve tried to do here is to revert this effect, while keeping the rhythms and overall colour harmony close to Chagall’s painting: that is to say, it’s now the figure that is virtually devoid of colour, warmth and matter – no more than slightest hints of the colours of its surroundings.

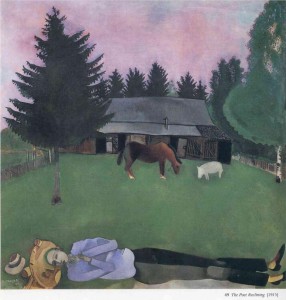

The second visual source is somewhat more vague, albeit more directly visible in the painting: some general impressions of cemeteries, pyramidal burial mounts, chapel windows. The figure is enclosed in a pyramid; it nearly is a pyramid (thou art the grave), albeit a transparent one, mirroring the rhythms of life around it.