William Shakespeare. Sonnet 20

A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou, the master-mistress of my passion;

A woman’s gentle heart, but not acquainted

With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion.

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling,

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth;

A man in hue, all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created;

Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

Simon Russel Beale reading this sonnet

This sonnet is a remarkable combination of playfulness and despondency. On the one hand, it jokingly plays around the impossible conceit of Nature pricking out someone who was originally designed as a woman because she fell in love with the person and wanted them for her own pleasure. On the other, it talks of what is construed as an insurmountable barrier, an ever-present distance between the speaker of the sonnet and his beloved.

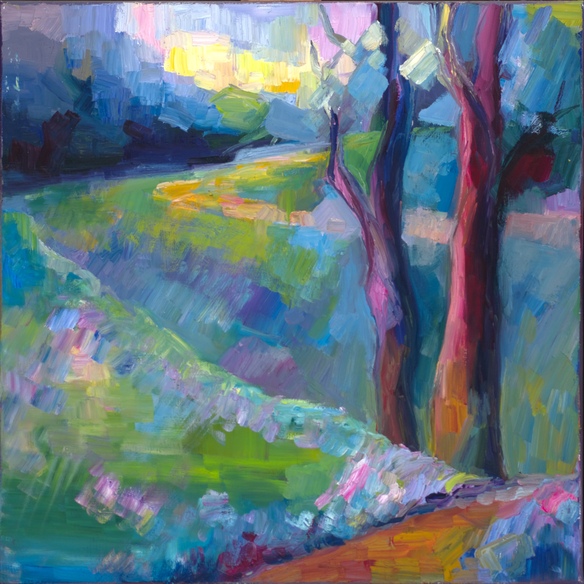

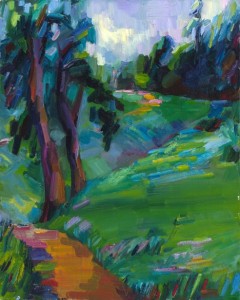

As a painter, my attention focused on the somewhat mysterious idea of all hues in his controlling, which suggested that the painting should play around “all hues”, that is, all colors of rainbow. This is really a case of strange serendipity, I thought, because this sonnet, for obvious reasons, is at the centre of debate on Shakespeare’s “real” sexual orientation; yet the association between the acceptance of all sexual orientations and the symbol of rainbow certainly belongs to our times, not to Shakespeare’s. And yet he does mention “all hues”, without any clear reason. Building the painting around a rainbow also conveys the feeling of insurmountable distance, impossibility of real closeness, accentuated by the water barrier between the viewer and the rainbow with all its hues.

Bringing together and controlling all hues with equal, or nearly equal, intensity is not an easy challenge for a painter. Here, I tried to carry this idea further than just a rainbow – splitting the colors into multiple hues in almost every single area of the canvas, pushing it to the same level of playful absurdity as the original conceit of the poem.