William Shakespeare. Sonnet 28

How can I then return in happy plight,

That am debarred the benefit of rest?

When day’s oppression is not eased by night,

But day by night, and night by day, oppressed?And each, though enemies to either’s reign,

Do in consent shake hands to torture me;

The one by toil, the other to complain

How far I toil, still farther off from thee.I tell the day to please him thou art bright

And dost him grace when clouds do blot the heaven:

So flatter I the swart-complexioned night,

When sparkling stars twire not thou gild’st the even.But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer

And night doth nightly make grief’s strength seem stronger.

Sam Alexander reading this sonnet

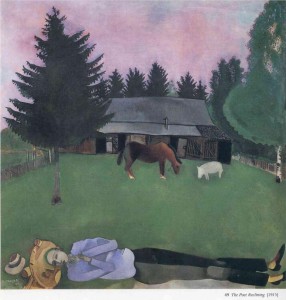

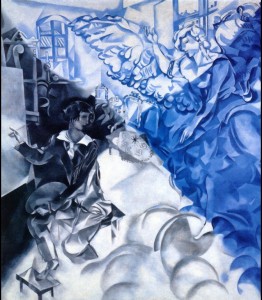

This sonnet continues the previous one: another letter in an exchange in which we hear only one voice. Yet the first line of this sonnet implicitly invokes the other person’s response, the request to return in a happy plight. In my series, the two paintings are connected by continuation of the same color harmony, dominated by sorrowful blues.

Yet if the first letter tries to be optimistic, with the sorrow of distance between the lovers softened by the speaker’s imagination, which fills his nights with the shining shadow of his beloved, here it turns into the constant source of torture, which wouldn’t let the speaker to forget and have the benefit of rest. The dreamy vision of the first letter turns into a hopeless struggle with the combined forces of eternal powers of Day and Night.

And if my Sonnet 27 painting stayed very close to the specific imagery invoked by the sonnet, here the subject matter, irises, might seem entirely disconnected from the content of the sonnet. Yet irises, their twisted shapes and their range of blues, presented themselves to me as the right “anchor” for a depiction of the tortured sorrow of separation. My path to this painting lay through a series of different approaches to irises, described here. In this final painting of the series, the flowers nearly dissolve into pure abstraction, a woeful, broken world created by conspiracy between lights and darks, Day and Night.