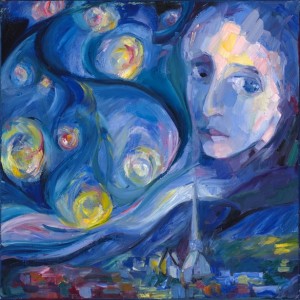

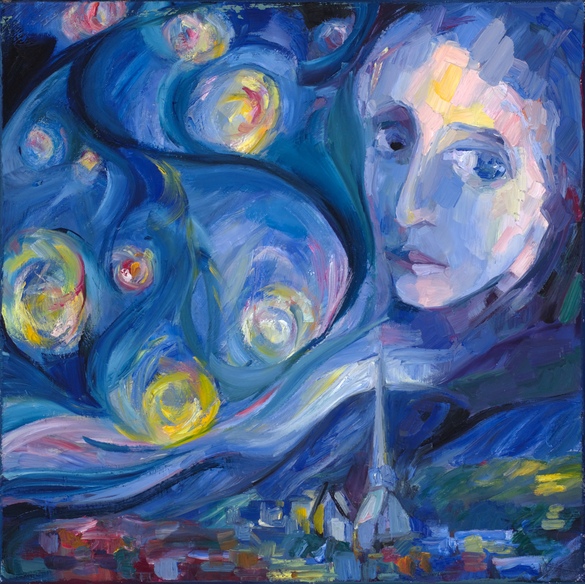

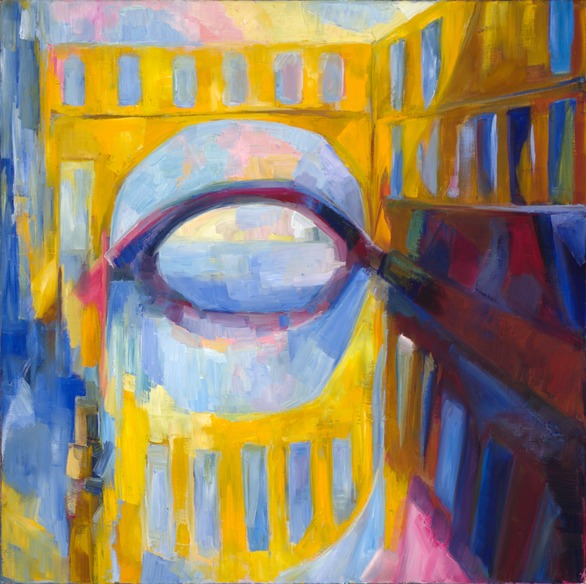

Sonnet 30: Remembrance of things past. 20″x20″. Oil on linen 2012

William Shakespeare. Sonnet 30

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste:

Then can I drown an eye, unused to flow,

For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night,

And weep afresh love’s long since cancelled woe,

And moan the expense of many a vanished sight:

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone,

And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er

The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan,

Which I new pay as if not paid before.

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restored and sorrows end.

Patrick Stewart reading this sonnet

When I only began thinking about the “Sonnets” series, about three years ago, I dreamed about some sort of intrinsic unity between the meanings and rhythms of the sonnets and my own direct impressions, both visual and emotional, reflected in the paintings. This process, the process of painting a poem, opens a new path to the very essence of what we now call “art”, its particular blend of personal and universal, “subjective” and “objective”, internal and external.

A piece of art means anything only insofar as it touches other people in a meaningful way (pun intended), resonates with their own internal strings and melodies; in other words, goes beyond “self-expression” into something beyond, larger than life of “self”, something universal and timeless, at least so long as men can breath and eyes can see. But there is no pathway to that place except through the deepest depth of one’s own mind and memories, where arbitrary individual traits are wiped away, and our love is one with everyone’s love; and our pain, one with everyone’s pain. And yet as a rule, you are completely alone on this path; you can only hope and trust that you’ve reached out to something deep enough to be meaningful, and enacted it in your work in an adequate way.

But here, when painting a sonnet, I am not alone at all. I am guided by a man who surely knew how to do it four centuries ago. For one thing, insofar as I find the state of resonance between my inner life and his, I may be as certain as humanely possible that there I am close to something universal, relevant to all humans, or at the very least not limited to my self. Even more importantly, I am learning to find the sense of harmony between the ways these meanings and feelings are enacted in a poem and in a painting: something I hoped for when I started, but couldn’t quite believe; the intense clarity of timeless connection.

Probably as any human being who has read the sonnets over these centuries, I find myself more deeply and directly touched by some of them, more detached, at least initially, from the others. Sometimes my path to the sonnet’s core is somewhat convoluted and confused, but every once in a while, like with this one, there is no path at all: I know exactly that place within myself; these very same sessions of sweet silent thought, with their repetitive waves of remembrances and newly alive feelings.

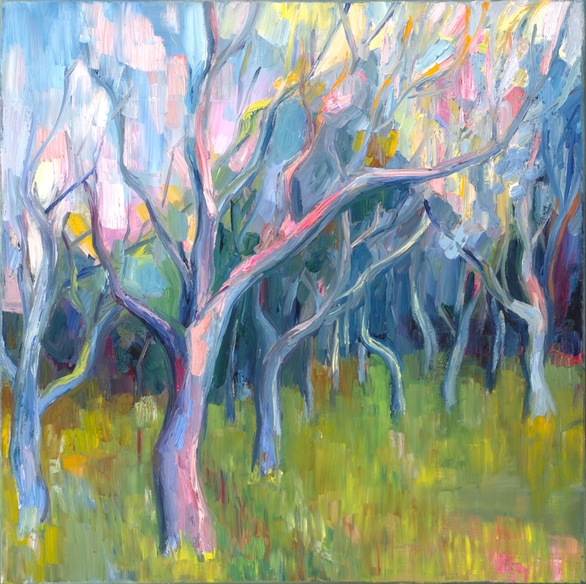

The place in the outer world that embodies this state of mind for me is deeply personal; and it certainly didn’t even exist in Shakespeare’s time: this view of the Winter Canal in St. Petersburg, crowded by the side walls of imperial buildings, but opening into the wide expanse of the Neva River. This is the place I used to love, my personal vanished sight, filled to the brim with lyrical and romantic associations. And yet, for all glaring idiosyncrasy, “self”-ness of this choice, this memory (since it is a memory depicted here, not the actual place) lies deep enough to be a non-arbitrary counterpart for the sonnet.

Why am I so certain of this, at least as certain as I can be? Because it resonates with the sonnet on all levels, semantically and formally, visually and rhythmically; to the extent that these levels merge and exchange places. To begin with, it has flowing water — a universal embodiment of time and reflection. Albeit not directly mentioned (except for the fleeting hints in drown and flow), water is present in the sonnet, in its waves of lexical repetitions and alliterations. Even reflections are there in the poem, in its multiple lexical pairs within lines (grieve and grievances, woe and woe, pay and paid, moan and bemoaned). One thing we can be absolutely sure of that it’s not for the lack of vocabulary that Shakespeare does this; it is a straightforward enactment of the process of remembrance.

As you see, the image picks up these patterns of repetitions of the sonnet in two ways: the doubling of the image by reflections in the water, and the repetitive motives of windows, with hints of reflecting sun in the glass. And the image itself is painted as remembrance, not as a cityscape viewed in the present: the reflections are larger and, at some places, more distinct than the objects they reflect; and at the edges of memory, the clear image dissolves: into abstract brushwork on the left; and into dream-like folding of structural planes on the right. And it is also the truth of how it was painted: I haven’t been there for many years now, and I painted the place as I remembered it, quite differently from how it’s depicted in multiple photographs (it _is_ one of photographers’ favorites in St. Petersburg).

And last but not least, the colour harmony: have you ever noticed how a shift of the red towards its colder variety, in the general direction of magenta, works in the primary red-blue-yellow colour scheme? It unmistakeably shifts the tonality of a piece from major to minor, from passionate joy to quiet longing; sadder, but it’s not the intense sadness of despair, but the tender, lighter sadness of remembrance. This is the colour harmony of this sonnet, as I see it in my mind’s eye: remembering old woes in the times of happiness. And this is the colour harmony of this place: dominated by yellows of the buildings and the blues of the sky, offset by the dark and muted cold reds of the granite of the embankments and the ground floors and the lightest cold reds of northern sunlight.