Those hours, that with gentle work did frame

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell,

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel:

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there;

Sap check’d with frost and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o’ersnow’d and bareness every where:

Then, were not summer’s distillation left,

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty’s effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it nor no remembrance what it was:

But flowers distilled though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet.

Click here to listen to Jemma Redgrave reading this sonnet.

One theory about Shakespeare sonnets is that the sequence started as a commission, in which the poet was engaged by someone to convince his young patron to marry and procreate, a topic which didn’t really touch Shakespeare on a personal level at the time. As the sequence progresses, two things begin to happen: the speaker’s love of the young man becomes more and more personal, passionate, and urgent; and he gradually gives up the idea of replicating his beloved through procreation. What takes its place is the idea much more significant to Shakespeare, and to his readers as well: the eternalizing power of art, more specifically, of his own poetry.

The fifth sonnet is the first time in the sequence where this idea is hinted at – it will disappear again in the next one, for some time, to return, much more explicitly and powerfully, later on. Here, what is suggested as a strategy against the winter of old age and death which inevitably destroys the beauty of summer is distillation. Shakespeare may seem simply to explore one more metaphor of procreation, but the process of making flowers into perfume – to be pent in walls of glass – creates something so essentially different from the original, that this metaphor leads him to a totally new meaning. After all, what the speaker was worrying about earlier in the sequence was preservation of the young man’s beauty (“show”); here, there is no hope of saving the “show”, only the “substance” may survive the coming winter.

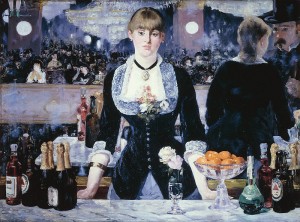

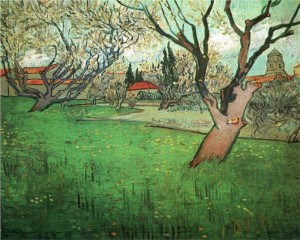

In my series, the art of poetry and eternalizing power of language must needs be replaced with the art of painting and eternalizing power of colour, and this is the first painting which begins to play with this concept. The major challenge posed by this aspect of translation is, of course, the opposition between “show” and “substance”: in the obvious sense, a painting is always about the “show” (as Shakespeare himself would remind us repeatedly later in the sequence).

For this first instance of Shakespeare’s engagement with this opposition, I chose to translate the loss of “show” as the loss of colour, contrasting the left vertical golden section rectangle, with it’s fully saturated colour harmony, and the right third of the painting, in which some muted ochres remain only in the background, and flowers themselves leese their colour (and lose their lusty leaves) and retain only their basic geometry. On another level, this loss of colour can be read as flowers being checked with frost, oversnowed – thus bringing in the second, wintery, quatrain of the sonnet.

The painting uses Shakespeare’s mention of frame in the first quatrain to introduce the “frame within frame” device, which transforms the canvas from just a depiction of flowers into an image aware of its being a painting. The internal, slanted, frame is ambiguous between two readings: It may be the frame of the painting – so that the painting represents both flowers themselves and a floral painting being painted (flowers distilled), or it may be the frame of a mirror in which real flowers are reflected, thus playing on Shakespeare’s original metaphor of their substance pent in walls of glass.