William Shakespeare. Sonnet 16

But wherefore do not you a mightier way

Make war upon this bloody tyrant, Time?

And fortify yourself in your decay

With means more blessed than my barren rhyme?

Now stand you on the top of happy hours,

And many maiden gardens yet unset

With virtuous wish would bear your living flowers,

Much liker than your painted counterfeit:

So should the lines of life that life repair,

Which this Time’s pencil or my pupil pen,

Neither in inward worth nor outward fair,

Can make you live yourself in eyes of men.To give away yourself keeps yourself still,

And you must live drawn by your own sweet skill.

Fiona Shaw reads this sonnet in the Touchpress edition.

In the dramatic plot of the sonnet sequence, we find ourselves at the crossing of three motives:

- Procreation as salvation, or Erasmian abjurations to marry. By all appearances, the speaker returns to this motive in this sonnet, yet it is about to dry out completely, to be replaced by

- Prohibited romantic love, with its mild craziness and enraptured adoration, supported and reinforced by

- Immortalizing power of art, from the poet’s cosmic view of earthly affairs – we have just been there in Sonnet 15 (to which this one is directly linked with the initial but of the first line), but now the speaker appears to have doubts about his power to make the young man live “in the eyes of men”.

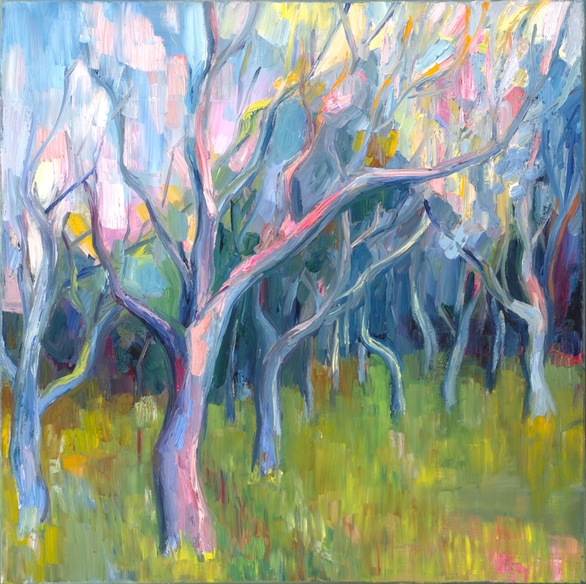

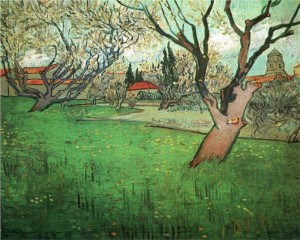

Although this sonnet seems to return to the procreation motive, we are just a breath away from (temporarily) forgetting mortality and different strategies of overcoming it and losing ourselves completely in the enchanted garden of romantic love. Even if the sonnet doesn’t mention romantic love explicitly, it is already filled to the brim with its sweetness and adoration. This is one reason why my painting picks the central visual image of the sonnet – maiden gardens yet unset (vaguely referencing Vincent Van Gogh’s orchard paintings, but without (visible) flowers).

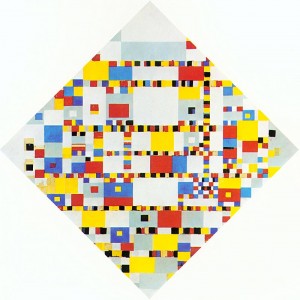

Here, however, the speaker still pretends to discuss the relative merits of immortalizing strategies. The major contrast is between art and procreation, with a sub-contrast between poetry and painting (by the way, it’s the first time that the speaker identifies himself as a poet, referring to his barren rhyme). The contrast is played out in two “linguistic” games.

The first game entertains the opposition and affinity between pencil (meaning painter’s brush) and the speaker’s own pen, creating a pun on penis (as the context suggests, that must be the instrument of the young man’s own sweet skill mentioned in the couplet). Just as the explicit mention of barren rhyme and maiden gardens create the empty place for the listener to fill in with fertile bride, so the explicit mention of inadequate “artistic” instruments of immortality, pen and pencil, suggest the only (yet shyly unnamed) adequate one, helped along by the phonetic similarity.

The second linguistic game is based on the multiple meanings of line:

- lines drawn by a (visual) artist, and

- lines of a poem, and, finally,

- the lines of life (i.e. genealogical lines).

This is the game I try to pick up and continue in the painting – stressing the linear qualities of organic branches (standing for lines of life) and attempting to match the magnificent rhythm of the third quatrain with the upward rhythmical movements of my lines.