Is it for fear to wet a widow’s eye

That thou consumest thyself in single life?

Ah! if thou issueless shalt hap to die,

The world will wail thee, like a makeless wife;

The world will be thy widow and still weep

That thou no form of thee hast left behind,

When every private widow well may keep

By children’s eyes her husband’s shape in mind.

Look what an unthrift in the world doth spend

Shifts but his place, for still the world enjoys it;

But beauty’s waste hath in the world an end,

And kept unused, the user so destroys it.

No love toward others in that bosom sits

That on himself such murderous shame commits.

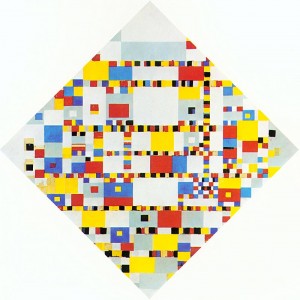

This translation into painting heavily relies on Helen Vendler’s observation [pp. 84-85] that the linguistic charm of the poem focuses on the symmetry of the word widow (widdow in the Quatro spelling), strengthened by the inherent symmetry of w, and plays with a flurry of related letters w, v and u and corresponding fluid sounds (some of these graphic relationships have been lost in the modern spelling: v used to be internally printed as “u”, and initial u, as “v”). For the painting, I’ve replaced widow with willow, the only other word with similar properties – or even better, since it retains the double l in the middle, a sound almost as “liquid” as w and u, and playing as important a part in the overall sound of the sonnet.

This change has two more advantages for my translation. On the semantic level, it gives me the image of weeping willow, naturally rhyming with the image of weeping, wailing, mournful world central to the poem. On the formal level, which really links language and imagery, the weeping willow’s shape is, in essence, a w turned upside down, with an additional play on the idea of symmetry.

Since the weeping, rainy sky had to play an essential role in the painting, I chose the lower golden section for the horizon line, giving me a plenty of space for the sky. As for the corresponding vertical (the other constant of the sonnet painting design), I first played with the seemingly obvious idea of using the trunk for it, but it worked neither on the representational level (the visible vertical trunk would break the image of the willow) nor on the painterly one. That’s why I focused on the other golden section vertical, suggested by one of the edges of the willow and an edge between colour areas within the willow, continued in the reflection. While the willow was painted from memory, the colours and lighting of the sky are done from life, from the skies above Fremont hills on two rainy, cold days of March, when the world indeed seemed to be mourning someone.

I kept the painting almost abstract, with under-defined, blurry forms – both in reference to no form of thee in the sonnet, and as a suggestion of vision of the viewer blurred by mournful tears.